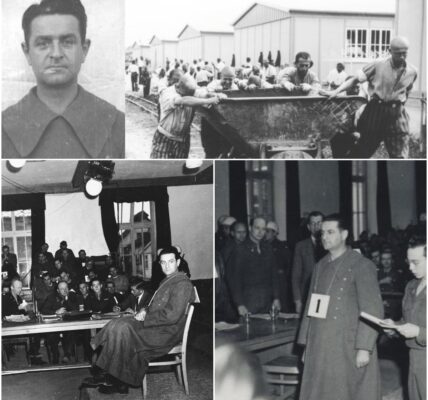

Rudolf Höss, the commandant of the Auschwitz concentration camp, was hanged next to the camp’s crematorium in 1947.

Rudolf Höss, the former commandant of the Auschwitz concentration camp, is one of the most well-known symbolic figures of National Socialist terror. His name is inextricably linked to the systematic mass murder that claimed the lives of millions of people during World War II. The last days of Rudolf Höss before his execution in April 1947 shed a powerful light on the end of a man responsible for one of the greatest crimes against humanity.

After the end of World War II, Höss initially went into hiding. Under the false name Franz Lang, he lived on a farm in northern Germany for several months. However, in March 1946, he was captured by British soldiers. Upon his arrest, he showed no remorse, instead defending his actions by claiming he was merely following orders. This line of reasoning ran like a thread through his later testimony—both before the Nuremberg Tribunal and before the Polish court that ultimately sentenced him to death.

During the Nuremberg Trials, Höss testified extensively about the organization and execution of the mass extermination at Auschwitz. He described with frightening sobriety the procedures in the gas chambers, the capacities of the crematoria, and his role in the logistical implementation of the “Final Solution.” His testimony provided the Allies and the international public with profound insight into the extent of the horror and made the full scope of the Holocaust tangible.

After his extradition to Poland in May 1946, Höss was imprisoned in Kraków. During this time, he wrote his memoirs, in which he attempted to explain his actions. There, too, he showed limited insight or remorse. His writings are now an important historical document, revealing the mindset of a man who was part of a perfidious system and who rarely questioned himself.

In March 1947, Rudolf Höss was tried before the Supreme National Tribunal in Warsaw. The charges were clear: crimes against humanity, mass murder, and complicity in the murder of over a million people, predominantly Jews. Höss pleaded guilty. Nevertheless, even in his closing statement, he stuck to his defense, saying he had “only done his duty.”

On April 2, 1947, the sentence was announced: death by hanging. The execution was to take place at the site of his crimes—in Auschwitz, not far from the former Crematorium I. On April 16, 1947, the sentence was carried out. Rudolf Höss was hanged on the grounds of the camp he had once had expanded himself.

Rudolf Höss’s last days were marked by outward calm, but inner emptiness. Contemporary witnesses report that he showed little emotion. In a letter to his family, he attempted to explain himself and begged for forgiveness, especially from his children. But for many, this was too late. The burden of his actions weighed too heavily.

While Rudolf Höss’s death marked the physical end of a man, it did not mark the end of the history of Auschwitz and the Holocaust. Rather, his death was a symbol—an expression of belated justice for millions of victims and survivors. The legacy he left behind is a warning to humanity.

Today, the Auschwitz Memorial is not only a place of remembrance, but also a place of enlightenment. The story of Rudolf Höss is not concealed there. On the contrary: his actions and fate are openly presented to show future generations where ideology, hatred, and blind obedience can lead.

The case of Rudolf Höss vividly demonstrates how a single person can become a cog in the machine of mass murder within a totalitarian system. But it also shows that responsibility doesn’t disappear within the system—but ultimately rests on the shoulders of those who act.