THE FEMALE DOCTOR OF DEATH: How Nazi Physician Herta Oberheuser’s Horrific Experiments Shocked the World

In the darkest chapters of human history, the atrocities of Nazi concentration camps like Auschwitz and Ravensbrück stand as haunting reminders of humanity’s capacity for cruelty. Among the perpetrators were not only men but also women like Herta Oberheuser and Herta Bothe, whose cold-blooded actions shocked the world. Oberheuser, a doctor who conducted horrific medical experiments, and Bothe, a brutal guard notorious for her violent beatings, embodied a chilling indifference to human suffering. Their stories, revealed through trials and witness accounts, expose the depths of their inhumanity. Dive into this analysis of their roles, their crimes, and the legacy of their actions, and share your reflections in the comments as we confront this grim history.

The stories of Herta Oberheuser and Herta Bothe reveal the terrifying roles women played in the Nazi regime’s machinery of death. From Oberheuser’s pseudoscientific experiments to Bothe’s sadistic brutality, their actions at Auschwitz and Ravensbrück left an indelible mark on history. Let’s explore their crimes, the consequences they faced, and the broader implications of their roles in the Holocaust.

Herta Oberheuser: The Doctor of Death at Auschwitz and Ravensbrück

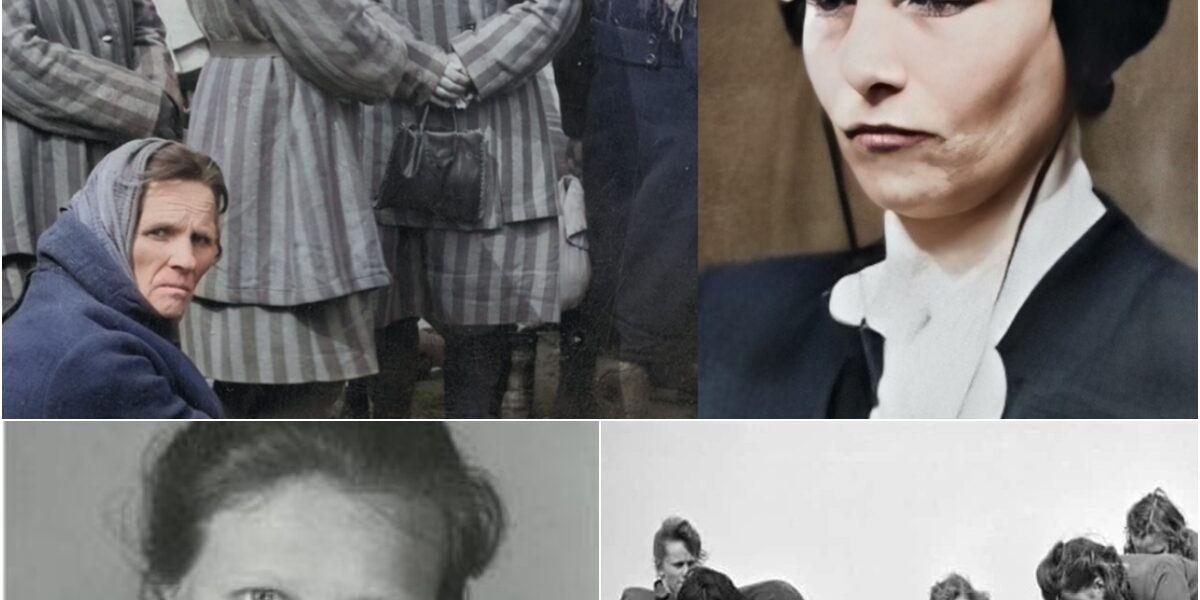

Herta Oberheuser, a physician in Nazi Germany, stands as one of the most infamous figures in the history of medical ethics violations. Stationed at Auschwitz and Ravensbrück, she conducted gruesome medical experiments on prisoners, primarily women and children, under the guise of scientific advancement. These experiments included injecting prisoners with bacteria to test infection responses, performing unnecessary amputations, and transplanting bones and muscles without anesthesia, causing excruciating pain and often death (per Holocaust Encyclopedia). Witnesses at the Nuremberg Trials testified to her chilling detachment, with one account describing how Oberheuser beat a Jewish prisoner named Eva to death with a stick and shot two others without provocation.

Oberheuser’s actions were not isolated but part of a broader Nazi program to exploit prisoners for pseudoscientific research. Her experiments aimed to simulate battlefield injuries, but they served no legitimate medical purpose, instead inflicting torture. An X post reflecting on her trial stated, “Herta Oberheuser’s experiments were pure cruelty disguised as science. How could a doctor sink so low?” Convicted at Nuremberg in 1947, she was sentenced to 20 years in prison for war crimes and crimes against humanity. However, her release in 1952 after serving only five years sparked outrage, with survivors arguing it was a miscarriage of justice. In 1958, her medical license was revoked, ending her career, but she lived until 1978, a free woman for decades (per Jewish Virtual Library). Her case raises questions about accountability and the complicity of medical professionals in atrocities.

Herta Bothe: The Sadistic Guard of Ravensbrück

Herta Bothe, another figure of infamy, served as a guard at Ravensbrück in 1942, a women’s concentration camp notorious for its brutal conditions. Known for her relentless cruelty, Bothe was feared for her violent beatings, often targeting prisoners for minor infractions or no reason at all. Witnesses described her as “cold and unfeeling,” with one survivor recounting how Bothe’s attacks left prisoners bloodied and broken (per United States Holocaust Memorial Museum). A photograph from August 1945, taken as she awaited trial, captures her stern demeanor, a chilling symbol of her role in the camp’s horrors.

Bothe’s brutality earned her a reputation as one of the most sadistic guards, with some accounts suggesting female perpetrators like her were even more vicious than their male counterparts. An X user remarked, “Herta Bothe’s cruelty at Ravensbrück was unimaginable. How could women do this to other women?” Her actions included overseeing forced labor, punishing prisoners with starvation, and participating in selections for the gas chambers. At the Ravensbrück Trials in 1946, she was convicted and sentenced to life imprisonment, though she was released in 1951 due to clemency. Bothe’s early release, like Oberheuser’s, fueled debates about justice for Holocaust perpetrators, leaving survivors to grapple with the pain of seeing their tormentors walk free.

The Role of Women in Nazi Atrocities

The cases of Oberheuser and Bothe challenge the stereotype that women were merely passive bystanders in the Holocaust. Both actively participated in the Nazi killing machine, wielding power over life and death with chilling indifference. Oberheuser’s medical training made her experiments particularly heinous, as she betrayed the Hippocratic oath to “do no harm.” Bothe, as a guard, used her authority to inflict physical and psychological terror. Historians note that women in the Third Reich, while fewer in number, were often as zealous as men in enforcing Nazi ideology, driven by propaganda, antisemitism, or personal ambition (per Yad Vashem).

Their actions reflect a broader pattern of complicity within the Nazi regime. Women like Oberheuser and Bothe were not anomalies but part of a system that rewarded cruelty and dehumanization. An X post posed a haunting question: “What drove women like Oberheuser and Bothe to such cruelty? Were they brainwashed, or was it something darker?” Their involvement underscores the complexity of perpetrator motivations, from ideological fanaticism to the allure of power in a genocidal regime.

Justice and Its Limits: The Nuremberg and Ravensbrück Trials

The trials of Oberheuser and Bothe at Nuremberg and Ravensbrück, respectively, were landmark moments in holding Nazi perpetrators accountable. Oberheuser’s 20-year sentence and Bothe’s life imprisonment reflected the severity of their crimes, yet their early releases—Oberheuser in 1952 and Bothe in 1951—highlighted the limitations of post-war justice. The clemency granted to many Nazi war criminals, often due to Cold War politics and West German reintegration, left survivors feeling betrayed. An X user lamented, “Five years for Oberheuser’s atrocities? Justice was not served for the victims of Auschwitz and Ravensbrück.”

The trials also exposed the scale of female involvement in the Holocaust. While men like Adolf Eichmann dominated headlines, women like Oberheuser and Bothe revealed the diverse roles perpetrators played. Their convictions set precedents for prosecuting medical crimes and camp brutality, but the leniency of their sentences raised questions about whether justice was truly achieved. The revocation of Oberheuser’s medical license in 1958 was a symbolic gesture, but for many, it came too late to address the pain of her victims.

Legacy and Reflection: Confronting a Dark History

The stories of Herta Oberheuser and Herta Bothe serve as stark reminders of the Holocaust’s horrors and the complicity of individuals within a genocidal system. Their actions—Oberheuser’s experiments and Bothe’s beatings—illustrate the depths of human cruelty, particularly when cloaked in authority or pseudoscience. Their early releases underscore the challenges of delivering justice in the aftermath of such atrocities, leaving a legacy of unresolved pain for survivors and their families.

Today, their stories are studied to understand the psychology of perpetrators and the mechanisms that enabled the Holocaust. Educational platforms like the Holocaust Encyclopedia and Yad Vashem emphasize the importance of remembering these women not as exceptions but as part of a broader system of terror. An X post reflected, “Learning about Oberheuser and Bothe is a gut punch. We must never forget how ordinary people became monsters.”

Herta Oberheuser and Herta Bothe, through their roles at Auschwitz and Ravensbrück, embody the chilling reality of female perpetrators in the Nazi regime. Oberheuser’s horrific experiments and Bothe’s brutal beatings reveal a shared indifference to human suffering, challenging assumptions about gender and cruelty. Their convictions at Nuremberg and Ravensbrück marked steps toward justice, but their early releases left wounds unhealed for survivors. As we reflect on their legacy, we confront uncomfortable questions about complicity, accountability, and the human capacity for evil. Share your thoughts in the comments—how do we ensure such atrocities are never repeated? Let’s honor the victims by keeping their stories alive.