AMERICAN MARTYR IN BERLIN: The Final Moments Before Execution of Mildred Harnack – America’s Forgotten Heroine Who Defied the Nazis

In August 1942, Mildred Harnack penned a hopeful letter to her family in Wisconsin, urging them not to worry despite the raging war in Europe. Months later, the Gestapo captured her in Nazi-occupied Lithuania, and Adolf Hitler himself ordered her execution. Harnack, an American scholar who moved to Berlin in 1929 with her German husband Arvid, joined the Red Orchestra, a resistance group that fought the Nazis from within. Her bravery in distributing anti-Hitler pamphlets, recruiting spies, and passing intelligence to the Allies cost her life, making her the only American woman executed on Hitler’s direct command. Decades later, her story—once buried by Cold War politics—has resurfaced as a testament to courage. This analysis explores Harnack’s journey from Milwaukee to Berlin, her role in the Red Orchestra, and the legacy of her sacrifice, offering a compelling narrative for history enthusiasts to share and debate on social media.

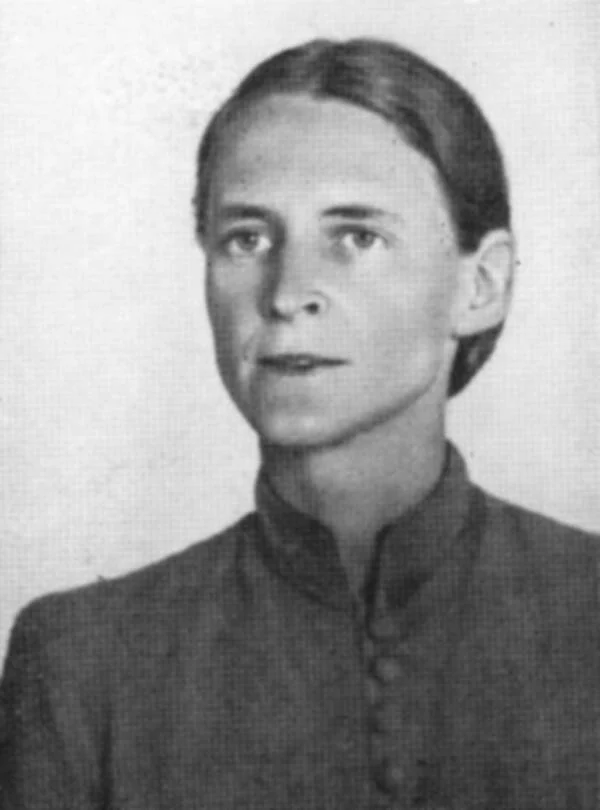

Mildred Harnack

From Milwaukee to Berlin: A Scholar’s Journey

Born Mildred Elizabeth Fish on September 16, 1902, in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, Harnack grew up bilingual in English and German, immersed in her neighborhood’s German community, per the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Aspiring to be a writer, she earned bachelor’s and master’s degrees in English literature and taught at her alma mater. In 1926, she met Arvid Harnack, a German lawyer and Rockefeller Fellow studying in the U.S., when he stumbled into her classroom by mistake, as recounted in Resisting Hitler by Shareen Blair Brysac. Their instant connection led to a whirlwind romance, with Arvid writing home, “I’ve met a girl with the beautiful name, Mildred,” per his sister Inge’s memoirs. They married on August 7, 1926, and after Arvid’s fellowship ended, Mildred joined him in Germany in 1929. Enrolling at the University of Berlin for her doctorate while teaching American literature, she thrived until 1931, when her outspoken criticism of the Nazis—“It thinks itself highly moral and like the Ku Klux Klan makes a campaign of hatred against the Jews,” she wrote in 1930, per the Los Angeles Times—led to her dismissal for not being “Nazi enough.”

Joining the Red Orchestra: A Dangerous Commitment

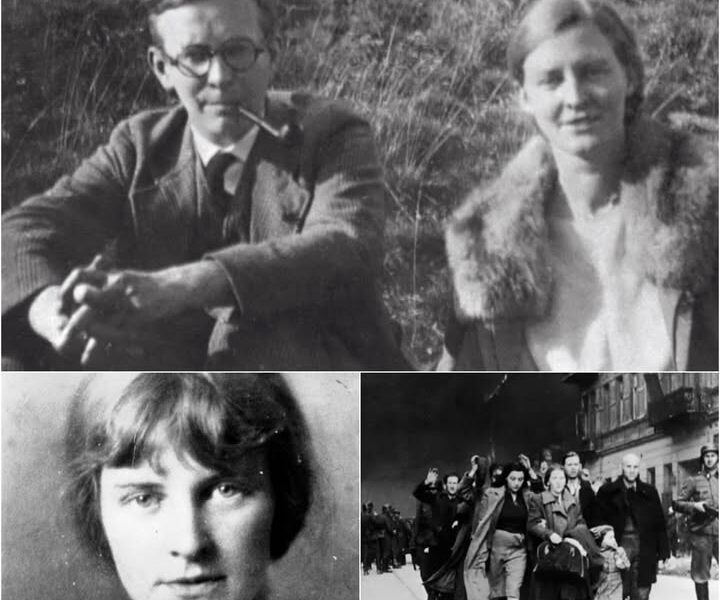

The German Resistance MuseumArvid and Mildred Harnack in Jena, Germany in 1929.

After losing her university position in 1931, Mildred and Arvid joined a small resistance group later dubbed the Red Orchestra by the Gestapo for its radio “concerts” relaying intelligence to the Soviet Union. Operating from 1933, the group distributed anti-Nazi pamphlets, documented Nazi atrocities, and, by the late 1930s, passed German economic and military secrets to the Soviets and Allies, per the German Resistance Museum. Mildred, teaching night school in Berlin, became a key recruiter, connecting disillusioned students to the resistance. Her role as a literary scout for a German publisher allowed travel across Europe, facilitating meetings with other resisters, per Brysac’s book. The Red Orchestra’s efforts, including warnings about Hitler’s 1941 invasion of the Soviet Union, were critical but perilous. In September 1942, the Gestapo intercepted a radio transmission, leading to the Harnacks’ arrest in Lithuania as they attempted to flee to Sweden. Mildred was imprisoned in Charlottenburg Women’s Prison, enduring daily interrogations, while Arvid faced trial for high treason, highlighting the couple’s unwavering commitment despite the risks.

Trial and Execution: Hitler’s Personal Vendetta

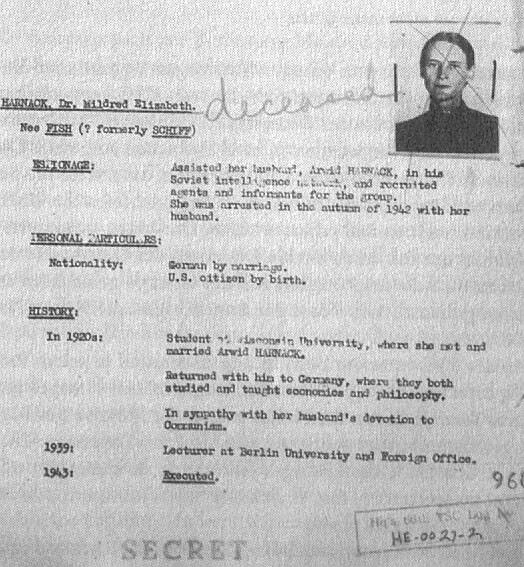

The U.S. Army’s file on Mildred Harnack was created around 1947.

In December 1942, Arvid Harnack was convicted of high treason and hanged with a short rope to prolong his suffering, writing to Mildred, “You are in my heart… My greatest wish is that you are happy when I think of you,” per Resisting Hitler. Mildred’s trial resulted in a six-year forced labor sentence, but Hitler, enraged by her espionage, overruled the judges and ordered her execution, per the New York Times. On February 16, 1943, at Plötzensee Prison, the 40-year-old was beheaded by guillotine, her death recorded as taking seven seconds, per Nazi documentation. Her final words, “And I have loved Germany so much,” reflected her complex bond with the country she fought to save from Nazism. As the only American woman executed on Hitler’s direct order, her death underscored the regime’s brutality and her singular courage, making her a martyr whose story resonates with those who value resistance against oppression.

Cold War Obscurity and Rediscovered Heroism

Post-war, the U.S. Army’s War Crimes Group investigated the Harnacks’ executions but concluded that Mildred’s actions, while “laudable,” constituted treason against Germany, closing the case due to her Soviet ties amid Cold War tensions, per a declassified memo. Former Nazis, seeking leniency at Nuremberg, falsely claimed the Red Orchestra was a communist spy ring active in the U.S., further tarnishing Mildred’s legacy, per The Red Orchestra by Anne Nelson. For decades, the Harnack and Fish families fought to clear their names, achieving recognition only after the Cold War. Today, Mildred is celebrated as a World War II hero, with schools in Berlin named after her and Arvid, per the German Resistance Museum. Her decision to stay in Germany, despite her family’s pleas to return to the U.S.—“It’s not a question of how dangerous it is, I’ve got work to do,” she wrote—highlights her sacrifice. Social media posts on X often cite her final words, sparking discussions about her patriotism and the moral cost of resistance, drawing parallels to modern fights against authoritarianism.

Legacy and Social Media Resonance

Mildred Harnack’s story captivates history enthusiasts on platforms like Facebook, where her bravery and tragic end fuel debates about heroism and sacrifice. Her role in the Red Orchestra, risking everything to undermine Hitler, resonates as a beacon of resistance, with users sharing quotes like her 1930 Nazi critique to highlight her foresight. The personal touch of her romance with Arvid, documented in letters, adds emotional depth, while Hitler’s direct intervention in her execution underscores her impact, making her a symbol of defiance. The Cold War’s role in obscuring her legacy prompts discussions about how politics shape historical memory, with X posts comparing her to modern whistleblowers. Her bilingual upbringing and academic ambition make her relatable, while her ultimate sacrifice—choosing duty over safety—sparks admiration and debate about the costs of standing against tyranny, ensuring her story remains a powerful narrative for today’s audiences.

Mildred Harnack’s journey from a Milwaukee scholar to a Nazi resistance fighter is a testament to courage in the face of evil. Joining the Red Orchestra with her husband Arvid, she risked everything to fight Hitler’s regime, only to be executed on his direct order in 1943. Her story, once buried by Cold War politics, now shines as a symbol of defiance, inspiring awe and reflection. For Facebook users, Harnack’s life offers a gripping blend of romance, bravery, and tragedy, sparking debates about what it means to resist oppression. Was she a reckless idealist or a selfless hero? As we honor her legacy, Mildred Harnack’s final words—“And I have loved Germany so much”—remind us of the profound sacrifices made for justice, inviting us to consider the courage it takes to stand up when the world falls silent.