“Before there was a number, there was a name: Aron Löwi.

Five days in Auschwitz and a photograph that survived his tormentors.

To remember is to resist.”

Who was Aron Löwi?

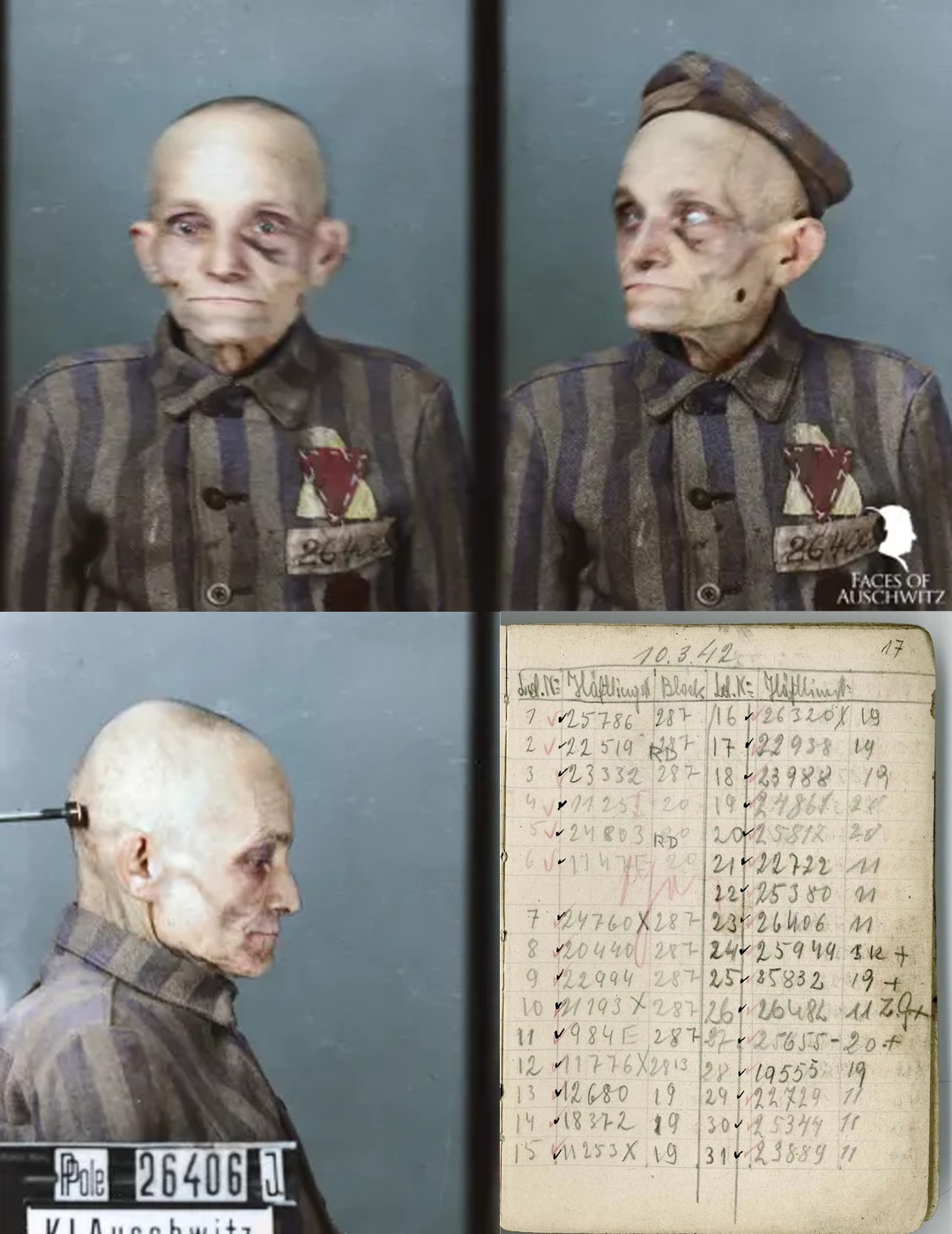

Aron Löwi was a Jewish merchant from Zator , a small town in Poland. On March 5, 1942, his name was reduced to a number: 26406. Transferred to Auschwitz from the prison in Tarnów , he was 62 years old—old enough to have lived a full life, young enough to still hope for peace. He died five days later , on March 10, 1942 .

What the photographs say:

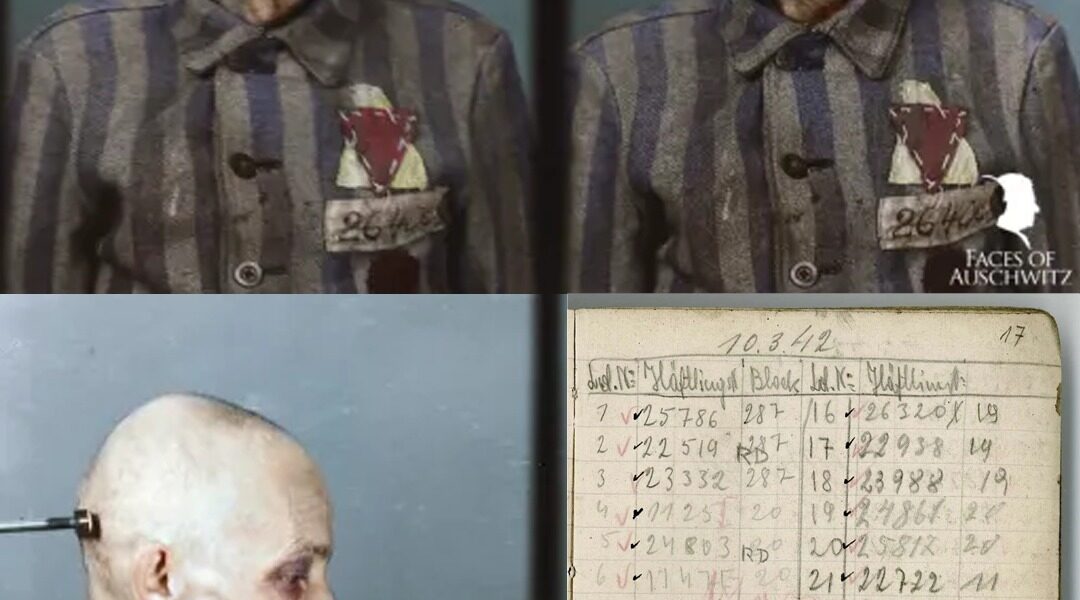

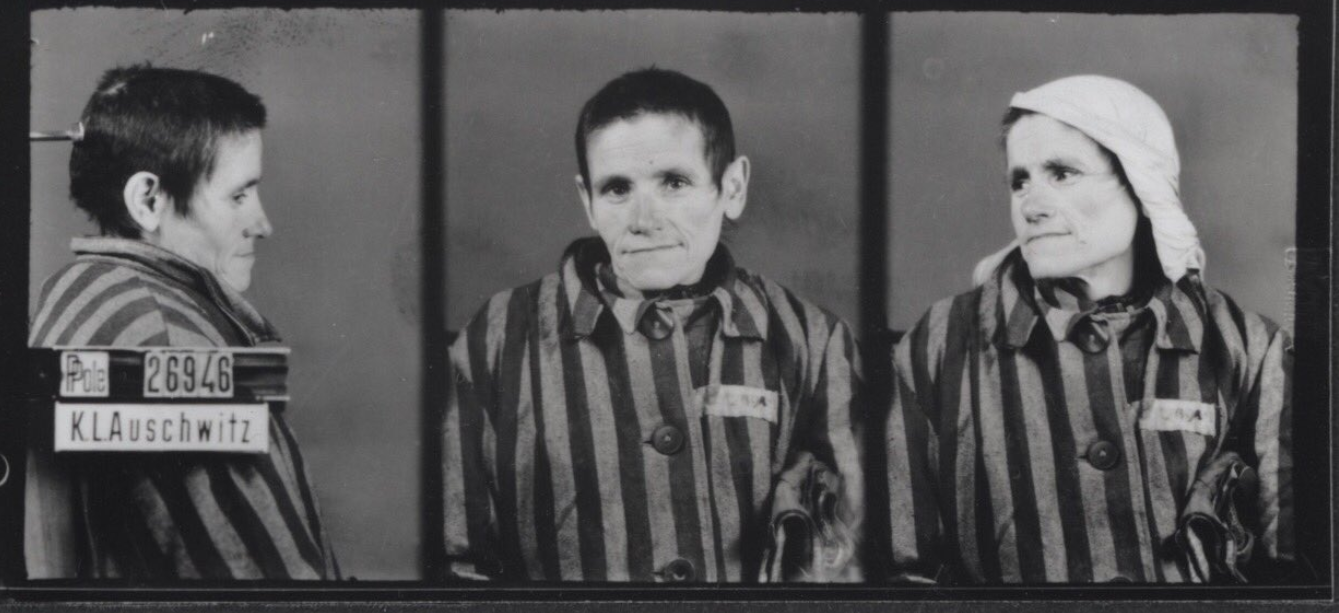

The three portraits (frontal, profile, and three-quarter view) follow the protocol of the camp’s identification service

. On Aron’s striped jacket, one can see the triangular insignia prescribed by the SS:

- Yellow to indicate Jewish identity ;

- Red for the “political” category .

In many cases, these triangles were superimposed to create a two-colored six-pointed star —a system that depersonalized and classified prisoners through colors and categories .

In his sunken eyes and the still-visible bruises, we read disbelief , exhaustion , and that form of silent resistance in the face of the unimaginable. The photos were taken at the moment when heads were shaved, personal belongings were confiscated, and a name was replaced by a number .

Five days, a single line in the register.

A register page dated March 10, 1942 , documents the administrative registration of Aron Löwi . As with so many others: no grave, no farewell —just a brief line in a notebook and a few photographs. Early deaths—often within the first week—were common: hunger, cold, illness, violence .

Portraits as Evidence—and as Reparation.

The Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum today preserves tens of thousands of registration photographs—only a fraction of the total collection destroyed during the Nazi retreat. Restoration and contextualization projects like Faces of Auschwitz give a face, a biography, and a voice to those whom the bureaucracy of murder had reduced to codes .

These images are forensic evidence , but also moral dialogues : They force us to look, to name, and to recognize the person behind the striped uniform. Every time we utter the name Aron Löwi , the machine that claimed to be able to erase him fails again .

Why keep looking? Because the photograph has outlived

those who took it . Because memory lasts longer than hatred . Because commemoration is a form of resistance —a way to give back to Aron Löwi and so many others what was violently taken from them: their humanity .