AMBUSH OF A CONVOY, WIPEWORK OF A VILLAGE: the brutal Nazi reprisal that killed hundreds of innocent Greeks

Content warning: This article deals with historical events involving extreme violence, war crimes, and the Holocaust, including the murder of civilians, which may be deeply disturbing. Its purpose is to educate about the atrocities committed by the Nazi occupation and the resilience of the survivors, and to encourage reflection on human rights and the prevention of genocide.

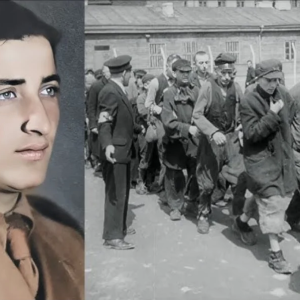

On June 10, 1944, the 4th SS Police Panzergrenadier Division massacred 218 civilians in Distomo, Greece, in retaliation for a partisan attack that killed seven German soldiers. Under the command of SS-Hauptsturmführer Fritz Lautenbach, SS troops burned villagers alive, shot women and children, and destroyed the village. The attack, ordered by division commander Herbert Ernst Vahl under the direction of SS-Generalmajor Heinz Lammerding to break the “spirit” of the population, was an example of Nazi terror tactics. This analysis, based on verified sources such as Wikipedia and eyewitness accounts from the Distomo Memorial, provides an objective overview of the massacre, its context, and the pursuit of justice, and encourages discussion about the human cost of the occupation and the value of remembrance.

The Nazi occupation of Greece and the growing resistance

World War II began on September 1, 1939, with the German invasion of Poland. The Battle of France (May 10–June 25, 1940) brought Germany victory over France, Belgium, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands within six weeks. Greece fell in April 1941 following the Italian and German invasions; the island of Crete was captured in May. The occupation divided Greece into Italian, German, and Bulgarian zones; the 4th SS Police Panzergrenadier Division (Edelweiss Division) was stationed in central Greece from 1943 onward.

The Greek resistance, including ELAS (People’s Liberation Army of Greece) under communist leadership, grew in the mountainous regions and carried out ambushes and acts of sabotage. To secure supply lines, SS commander Lammerding ordered reprisals. On June 9, 1944, the 3rd Battalion under Major Helmut Kämpfe hanged 99 men in Tulle, France, in retaliation for a similar ambush—a signal for the beginning of purges.

The Distomo Ambush and Massacre

On June 10, 1944, near Steiri, Greek partisans attacked a German convoy of the 2nd Company, 1st Battalion, 7th SS Panzergrenadier Regiment, killing 40 soldiers, including seven from Lautenbach’s unit. Enraged, Lautenbach led 120 to 200 SS soldiers to Distomo, five kilometers away, under the pretext of an identity check.

The village, home to about 650 people, was peaceful and had no connection to partisans, according to survivors like Robert Hébras. The troops herded the men into barns to shoot and burn them, and the women and children into the church, where grenades and incendiary devices killed 207. Machine guns fired on fleeing villagers. By evening, 218 people lay dead, including 109 women and 109 children; the village was looted and burned to the ground.

Lautenbach’s report falsely claimed that Distomo had opened mortar and machine-gun fire to justify the attack. An agent of the Secret Field Police, Georg Koch, contradicted this, stating that the ambush had taken place several kilometers away.

Divisional leadership and overarching context

The 4th SS Police Division, under the command of Herbert Ernst Vahl, acted on the orders of Lammerding, who had ordered the elimination of partisans. The unit, composed of police and SS forces, was notorious for its reprisal actions. Lammerding, who was later convicted in absentia, escaped actual punishment.

The massacre was in line with the Nazi strategy of collective punishment, in which 50 civilians were to die for every German killed. In Greece, this policy led to the deaths of approximately 80,000 civilians by 1944.

Resistance and immediate consequences

The resistance intensified its attacks, ambushing SS convoys and disrupting their supplies. Maquis actions delayed the advance of the “Das Reich” division into Normandy and contributed to the success of D-Day. Survivors like Marguerite Rouffanche testified, fueling the search for justice.

After the massacre, George Wehrly of the Red Cross reported about 600 dead in the region, some bodies hanging from trees.

Post-war trials and justice

In the Bordeaux trial of 1953, 21 members of the “Das Reich” division were indicted: 14 Alsatians (“Malgré-nous”) and two Germans were sentenced to death, but the sentences remained lenient. Lammerding lived undisturbed in Germany until 1971, benefiting from the statute of limitations. Diekmann died in 1944.

In 1997, Greek courts awarded €16 million in compensation, but Germany refused to pay, citing treaties from 1960. The 2014 ruling by the European Court of Human Rights was in favor of Greece, but had no effect.

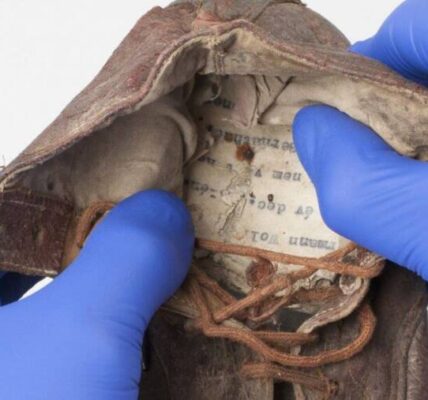

The ruins of Distomo, preserved as a memorial, symbolize unfinished justice.

The Distomo massacre, in which 218 innocent people were killed in retaliation for the deaths of seven soldiers, embodies the brutality of National Socialism. Lautenbach’s unit, under Vahl and Lammerding, destroyed the village, but the resistance ultimately contributed to victory. For those interested in history, Distomo serves as a reminder of the importance of remembering the victims, preventing genocide, and defending human rights. Verified sources like Wikipedia ensure objective information and promote empathy and vigilance against all forms of hatred.