In the spring of 1945, Europe breathed again—but in the footsteps of the Allied armies, this breath of freedom mingled with the stench of ash and death.

Behind the retreating enemy lines, they discovered places no one could have imagined—landscapes of industrial horror: the Nazi concentration and extermination camps.

What they found in Buchenwald , Dachau , Bergen-Belsen , Mauthausen , and Auschwitz was not just the trace of a crime: it was the absolute silence of vanished humanity.

The soldiers, hardened by years of war, suddenly froze in shock.

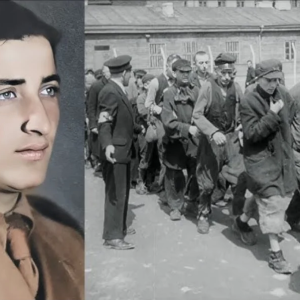

Before them stood living beings, barely recognizable: skeletal figures, barefoot in the mud, wrapped in striped rags, with hollow eyes that were nevertheless capable of a single gaze – that of survival.

Some stretched out their hands, others hid, as if still fearing death.

When an American soldier offered a piece of bread, several burst into tears.

This simple gesture, commonplace in a normal world, became an act of resurrection here.

The first liberation was that of Majdanek in July 1944, when Soviet troops discovered a camp that was still partially operational.

Then came Auschwitz , in January 1945—the largest and most terrifying of all.

The Soviets found piles of shoes, hair, eyeglasses, human teeth.

Carriages full of objects torn from interrupted lives.

On that day, humanity understood that barbarity could be planned, quantified, and methodically organized.

In April 1945, American troops reached Buchenwald and Dachau .

Reports describe the soldiers’ silence: men accustomed to war, but unprepared to discover a war against the human soul.

Warehouses full of ash, still-warm stoves, mountains of corpses.

And amidst it all, survivors, too weak to grasp that they were free.

One officer wrote in his notebook: “We thought we had seen everything. We had seen nothing yet.”

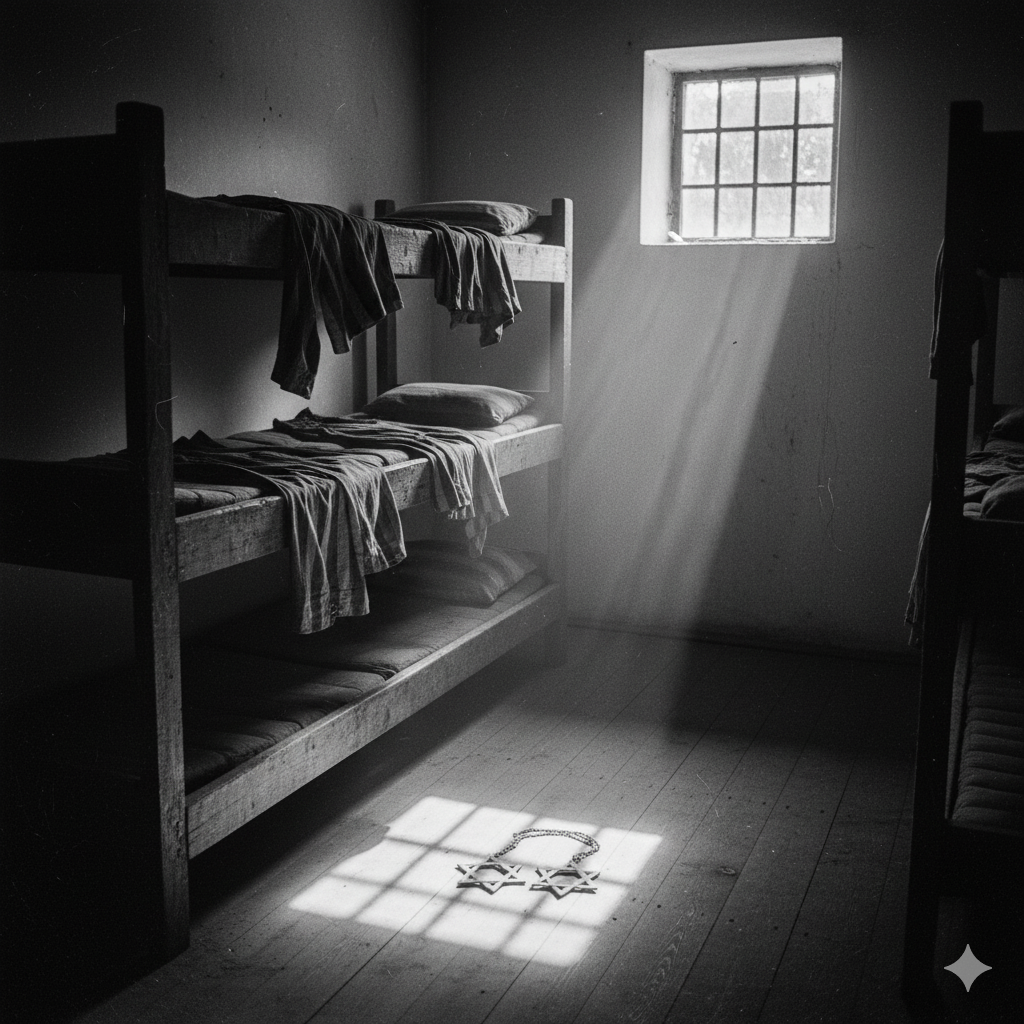

For the survivors, freedom came like a distant dream, almost unbearable.

Some collapsed as they approached the exit; others refused to leave the barracks, too broken to believe the nightmare was over.

But those who managed to pass through the iron gate—often marked with cynical slogans like “Work sets you free” —took this step as an act of rebirth.

One man raised his eyes to the sky and whispered, “At last, silence is human.”

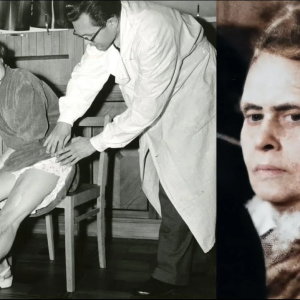

Reconstruction was slow, painful, marked by hunger, disease, and above all, loss.

Entire families had vanished, names erased, languages reduced to whispers.

Yet, in the heart of this emptiness, some found the strength to bear witness, to speak, to bring back to life those whom they had sought to extinguish.

Through them, memory took hold where life had been extinguished.

The photographs taken during the liberation have become universal symbols.

They show not only the misery of the survivors, but also the first spark of humanity returning to a devastated world.

They remind us that a single glance, a gesture of sharing, a word like “freedom” can outweigh the deepest hatred.

These images endure even today, surviving the decades.

They compel us to look, to understand, to pass them on.

For to forget would be to open the door to the return of evil.

To remember means to keep alive the fragile light that once almost went out.

The day the Allied soldiers opened the gates of the camps did not just end a war.

It was the return of humanity itself – fragile, trembling, but standing upright.