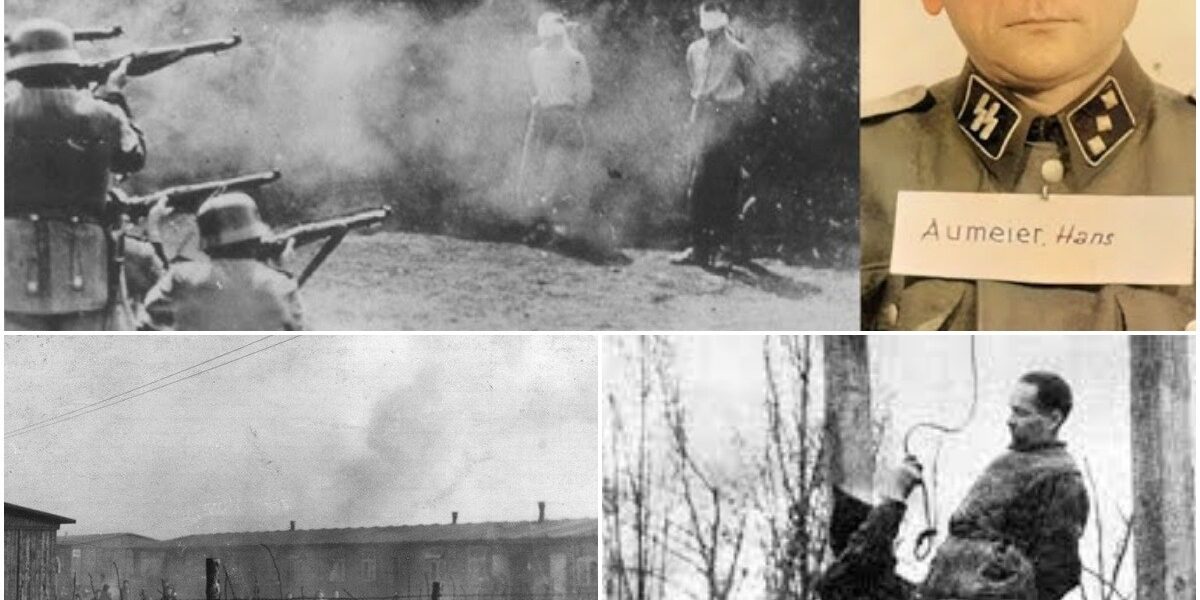

“THE DEPUTY: Inside the brutal regime of Hans Aumeier, the man who oversaw the crematoria and had 144 women executed in a single day.” _de105

In the dark annals of the Holocaust, few figures embody the cold machinery of genocide as much as Hans Aumeier. As deputy commandant of Auschwitz I, this SS-Hauptsturmführer was not merely a bureaucrat in Hitler’s extermination camps—he was an architect of terror who personally carried out the atrocities. Under his supervision, the main camp became a labyrinth of forced labor, systematic mistreatment, and mass executions, where human lives were incinerated in the crematoria he personally oversaw. Aumeier’s legacy is etched in the screams of the condemned: On a single spring day in 1942, he ordered the execution of 144 women against the blood-stained wall of Block 11. Their bodies remained as a gruesome testament to his relentless cruelty. This is the story of a man who transformed obedience into atrocity, and whose end came not in glory, but on the gallows.

From unknown craftsman to SS executioner

Hans Aumeier was born on August 20, 1906, in the Bavarian town of Amberg, far removed from the ideological turmoil of postwar Germany. The son of an experienced turner and locksmith in a rifle factory, young Hans followed a predetermined path: four years of elementary school, three years of secondary school, and then an apprenticeship in the same trade. As early as 1918, at the age of only twelve, he left school without graduating and eked out a living in factories in Munich, Berlin, Bremen, and Cologne. The unemployment during the Weimar Republic’s economic crisis took its toll on him, forging a restless spirit ripe for radical views.

Aumeier’s entry into the Nazi world was inconspicuous yet fateful. In December 1929, he joined the National Socialist German Workers’ Party (NSDAP), drawn by the promise of stability and purpose. Two years later, in 1931, he volunteered for the Sturmabteilung (SA), the party’s paramilitary wing, before transferring to the elite Schutzstaffel (SS) later that same December. Assigned as a driver at SS headquarters under Heinrich Himmler’s supervision, Aumeier rose through the ranks through loyalty and connections. By the end of the 1930s, he had honed his skills within the repressive apparatus of the Third Reich and held various administrative positions that foreshadowed the horrors to come. No one suspected then that this former factory worker would soon be directing the extermination of thousands of people.

The Descent to Auschwitz: Architect of the Main Camp’s Nightmares

Aumeier’s true baptism of fire began on February 1, 1942, when he arrived at Auschwitz I as the new Protective Custody Camp Leader (SLA) and head of Department III. He replaced Karl Fritzsch and took over a sprawling complex of barbed wire and barracks that had already claimed countless lives. As deputy to Camp Commandant Rudolf Höß, Aumeier exercised virtually unlimited power over the daily operations of the main camp and enforced a draconian disciplinary regime that blurred the line between labor and liquidation.

His responsibility was as immense as it was abhorrent. Aumeier oversaw the forced laborers who toiled prisoners to exhaustion in munitions factories and on construction sites. Malnutrition and mistreatment claimed more victims there than the quotas had to be met. He granted criminal Kapos—trusted, sadistic prisoner guards—unfettered power, which further intensified the terror in the camp. Whips cracked, fists flew, and fear hung heavy in the air under his gaze. But it was Aumeier’s oversight of the crematoria that made him immortal as “Death’s representative.” He ensured the efficient disposal of corpses through gassing, shooting, and starvation, transforming the ovens into a relentless machine of industrial murder. Witnesses later described how he strode through the smoke-filled courtyards, barking orders as the flames consumed the evidence of his crimes.

Aumeier’s brutality was not abstract, but personal and grotesque. He reveled in the spectacle of punishment, personally administering blows with a riding crop or his fists to any prisoner who hesitated. Testimonies from survivors describe him as a man with a fiery temper who ordered floggings even for the slightest offenses. In a terrifying escalation, he participated in mass reprisals following prisoner escapes, in which entire city blocks were razed to the ground to spread collective fear.

A day of carnage: The execution of 144 women

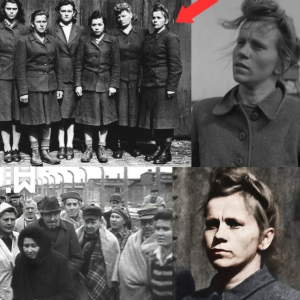

No single act illustrates Aumeier’s cruelty more clearly than the massacre of March 19, 1942. In the courtyard between Blocks 10 and 11—the infamous “death block” of Auschwitz I—144 Jewish women, selected from arriving transports, were lined up against the execution wall. Aumeier, the ever-meticulous officer, gave the order personally. SS guards raised their rifles, and in the hail of bullets, the women fell to the ground, their pleas silenced forever. The bodies were left to decay as a memorial and only later, under Aumeier’s supervision, were they taken to the crematoria.

This was not an isolated incident. Just over two months later, on May 27, 1942, Aumeier stood idly by as 168 more prisoners—men and women—met the same fate at the same wall. And on June 10, 1942, in retaliation for a mass escape attempt by the camp’s penal company, he oversaw the execution of dozens of survivors, their blood mingling with the spring mud. These executions were not mere punishments; they were a spectacle designed to break the survivors’ will to live and to satisfy Aumeier’s insatiable lust for power.

Yet even in this inferno, Aumeier’s downfall was foreshadowed. In August 1943, rumors of his corruption reached Berlin. He was accused of embezzling gold teeth and valuables from gassing victims. He was transferred out of Auschwitz in disgrace—degraded in the eyes of his superiors from a monster to a mere thief. It was a rare touch of irony in an otherwise seamless descent into evil.

Exile and the Illusion of Salvation

Aumeier’s release from Auschwitz did not end his complicity. Promoted to SS-Sturmbannführer (major), he was transferred to Estonia as commandant of the Vaivara concentration camp, where he continued to conduct selections for the gas chambers and was responsible for the deaths of thousands through starvation and death marches. In August 1944, as the Red Army advanced, he evacuated the camp, driving the survivors to their certain death. Briefly assigned to a police battalion near Riga, he participated in killings modeled on the Einsatzgruppen before being transferred to his final posting: the short-lived Mysen concentration camp in Norway, which opened on May 7, 1945 – just days before Germany’s surrender.

In a bizarre turn of events, Aumeier showed a fleeting flicker of humanity in Mysen. He negotiated with the Norwegian Red Cross for aid supplies and released prisoners the day after liberation. Some historians suspect it was self-preservation, an attempt to whitewash his past as the Allies drew ever closer. But the redemption was an illusion; the ghosts of Auschwitz haunted him like smoke from the crematoria.

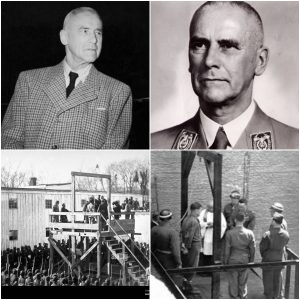

Justice at the gallows: The Krakow trial

The Allied victory was followed by swift reprisals. On June 11, 1945, British troops arrested Aumeier at the Terningmoen camp in Norway and unmasked him using Gestapo files. During interrogation by MI6 and the US intelligence service, he initially denied any knowledge of the gas chambers and claimed to have known nothing about the extermination operations at Birkenau, just a few kilometers from his post. However, under pressure—and later in detailed statements that came to light in 1992—he confessed to having overseen the gassings in Bunkers 1 and 2 and described the Zyklon B process with chilling precision.

After his extradition to Poland in 1946, Aumeier stood trial before the Supreme National Tribunal in Krakow from November 25 to December 16, 1947, in the First Auschwitz Trial. Accused along with 39 other SS men, he resisted and maintained that he had not personally killed anyone. The testimonies of survivors refuted his claim: accounts of beatings, executions, and the incessant roar of the crematoria ovens portrayed him as a willing cog in the machine of the Nazi killing apparatus. On December 22, 1947, the court sentenced him to death for crimes against humanity.

On January 24, 1948, Hans Aumeier, the deputy death judge, met his end within the grim walls of Montelupich Prison. At the age of 41, he was led to the gallows and hanged; his neck snapped in the cold Polish winter air. As the trapdoor fell, the last breaths of 144 women—and countless others—finally ceased.

A legacy from ashes

Hans Aumeier’s story is a harrowing reminder of how ordinary men can become monsters under the banner of an ideology. From the factories of Bavaria to the firing squads of Auschwitz, his life was a steadily escalating descent into depravity, a descent only brought to an end by the scales of justice. Today, as we commemorate the six million murdered souls of the Holocaust, Aumeier’s name serves as a warning: evil thrives not in the exceptional, but in the conformist. The crematoria he oversaw may be extinguished, but the flames of remembrance burn eternally, ensuring that harbingers of death like him are never forgotten.