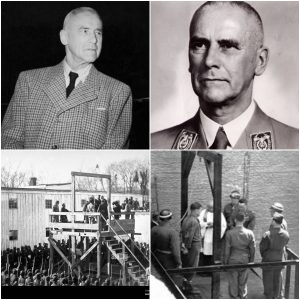

“BEYOND THE HAGUE JUDGMENT: The icy calm and the last defiant cry of Arthur Seyss-Inquart – the architect of the destruction of the Netherlands, who sent hundreds of thousands to their deaths and plunged through the gallows’ trapdoor at 2:45 a.m.” _de106

In the gloomy, echoing gymnasium of Nuremberg Prison, as the clock passed 2:40 a.m. on October 16, 1946, a limping figure ascended the wooden scaffold—the last of ten condemned Nazi architects to face the gallows. Arthur Seyss-Inquart, the bespectacled bureaucrat whose clubfoot mirrored the convoluted path of his ideology, climbed the thirteen steps with uncanny composure. His voice, deep and penetrating, was a final plea for peace amidst the ruins of the war he had helped to ignite: “I hope that this execution is the final act of the tragedy of the Second World War, and that the lesson of this war will be that peace and understanding should prevail among nations.” But as the trapdoor opened beneath him, his composure shattered into a guttural roar: “I believe in Germany!”—a defiant cry that echoed through the hall like a ghost refusing to die. At 2:45 a.m., Seyss-Inquart fell through the gallows, his body twitching in the final gasp of a regime that had devoured entire nations. This was not merely an end; it was the terrifying conclusion of a life built on destruction, of a man who—much like his counterpart Hans Frank in occupied Poland—had transformed sovereign territory into slaughterhouses of the soul.

Arthur Seyss-Inquart was born on July 22, 1892, in Stannern (now Hranice na Moravě in the Czech Republic), Bohemia. He came from the ruins of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy, was a highly decorated veteran of the First World War, wounded in the war, and later a lawyer in Vienna. In the 1930s, his fervent Pan-Germanism brought him under the influence of the National Socialists. He represented the “legal” faction of the Austrian National Socialists and advocated the annexation of Austria by Germany while serving as Minister of the Interior and Security in the government of Chancellor Kurt Schuschnigg. When Hitler sought to appoint him Chancellor on March 11, 1938, Seyss-Inquart complied without hesitation and held the office for only two days before German troops crossed the border. He welcomed the invasion with open arms, became Reich Governor of the newly created province of Ostmark, purged the professions of Jews, and thus laid the foundation for the Holocaust in his homeland.

Seyss-Inquart’s rise was unimpeded. In May 1939, Hitler appointed him Reich Minister without Portfolio, and by October he was serving under Hans Frank as Deputy Governor-General in the brutal General Government of occupied Poland—a territory Frank administered with genocidal zeal and where he was responsible for ghettos, mass shootings, and the deportation of millions to extermination camps like Auschwitz and Treblinka. Seyss-Inquart, the ever-efficient administrator, mirrored Frank’s territorial tyranny: he suppressed resistance, enforced Aryanization, and ensured the smooth operation of the killing machine. Their roles were eerily parallel—bureaucrats of barbarity who transformed conquered territories into laboratories of death, where human lives were reduced to quotas on balance sheets.

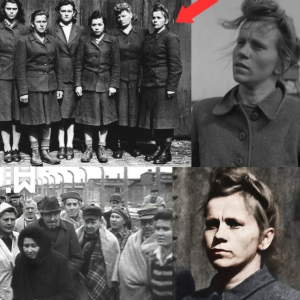

But in the Netherlands, Seyss-Inquart’s campaign of annihilation crystallized into a notorious reputation. Appointed Reich Commissioner on May 29, 1940, just weeks after the Blitzkrieg, he ruled the five-year occupation with kid gloves rather than an iron fist and was directly subordinate to Hitler. From his headquarters in The Hague, he orchestrated a campaign of calculated cruelty. He banned opposition parties, politicized culture through the Dutch Chamber of Culture, and deployed the paramilitary Dutch Guard to terrorize dissidents. Strikes in Amsterdam, Arnhem, and Hilversum in 1943 were immediately punished: summary trials before military courts, collective fines of 18 million guilders, and over 800 executions—some sources cite more than 1,500—of hostages, resistance fighters, and innocent bystanders caught in the crossfire. During the 1944 raid in Putten, a reprisal for an attack on SS leader Hanns Albin Rauter, 117 villagers were shot dead and thousands deported; their village was razed to the ground.

But Seyss-Inquart’s most devastating decree targeted the Jews. A ruthless anti-Semite, he acted swiftly: within a few months, he purged them from the civil service, the press, and industry. By 1941, 140,000 Dutch Jews had been registered, herded into the Amsterdam ghetto, and deported through the Westerbork transit camp—a former refuge that had become a conveyor belt to hell. The roundup in February 1941 deported 600 to Buchenwald and Mauthausen; until the end of the war, trains rattled ceaselessly to Auschwitz, claiming 107,000 lives. Only 30,000 Dutch Jews survived—a 75% extermination rate unparalleled in Western Europe. As the Allies advanced in September 1944, he redirected the survivors to Theresienstadt, a facade of mercy that masked further carnage.

Forced labor was his second scourge. Under his rule, 530,000 Dutch civilians were forcibly recruited, 250,000 of them deported to German factories as forced laborers, where their bodies were broken in the service of the Reich. Camps like Herzogenbusch (Vught), Amersfoort, and the infamous Erika near Ommen became outposts of his terror state. In the Hunger Winter of 1944–45, another 20,000 people starved to death, as his policies undermined food supplies amidst scorched-earth retreats—although, in a rare display of restraint, he negotiated Allied airlifts in April 1945. In total, Seyss-Inquart’s death register recorded hundreds of thousands: Jews were gassed, forced laborers murdered, hostages killed, and civilians starved to death. He was the architect of the Dutch annihilation, a quiet engineer whose decrees were reminiscent of Frank’s Polish strategy, but on the windswept dunes of the Netherlands.

With the collapse of the Third Reich, Seyss-Inquart’s star faded. In Hitler’s will of April 1945, he was appointed Foreign Minister—an empty honor in the madness of the bunker. On May 5, 1945, he was captured in Hamburg by British troops—ironically, by a German Jewish survivor of a Kindertransport—and tried before the International Military Tribunal in Nuremberg. Defended by Gustav Steinbauer, he achieved an outstanding score of 141 on an IQ test, placing him second only to Hermann Göring among the defendants. This testified to the intelligence that drove his atrocities. Acquitted of conspiracy, he was convicted on all other charges: crimes against peace, war crimes, and crimes against humanity. The judges condemned his reign of terror in the Netherlands—the deportations, the executions, the relentless oppression of the nation.

In his final testimony before the court, Seyss-Inquart claimed to have known nothing of the atrocities and asserted moral qualms about the deportations of the Jews, which he nevertheless equated with the Allied expulsions of Germans after the war. “My conscience is clear,” he declared, claiming to have “improved” the situation in the Netherlands—a grotesque revisionism from the man who had led an entire nation to ruin. At the sentencing, he shrugged fatalistically: “Death by hanging… well, given the circumstances, I expected nothing else. It’s alright.” He returned to the Catholic faith and asked the chaplain, Father Bruno Spitzl, for absolution, but the blood on his hands could not be washed away.

On that autumn night, the execution chamber resembled a theater of retribution. One after another, the condemned men—Keitel, Kaltenbrunner, Rosenberg, Frick, Streicher, Sauckel, Jodl, Frank, and Ribbentrop—fell to the floor, their bodies swinging like pendulums of justice. Göring, who had escaped the gallows by committing suicide, lay carelessly beside him. Seyss-Inquart, the last, limped forward, his unsteady bearing the iron will of his convictions. Guards supported him as he uttered his rehearsed hope for peace, a hollow echo in a hall filled with the cries of millions. Then, as the lever was pulled, the cry rang out: “I believe in Germany!”, a final, hoarse declaration of allegiance to the fatherland that had spawned its monster. At 2:45 a.m., his neck snapped, the dull thud of the trapdoor marking the end of Nuremberg’s gruesome spectacle.

Seyss-Inquart’s body was cremated in Munich’s East Cemetery, his ashes anonymously scattered in the Isar River—the unrepentant man was even denied a grave. Beyond the verdict—not in The Hague, but in the Bavarian court that redefined justice—his end reveals the banality of bureaucratic evil. He was no fanatical agitator like Streicher, no ideologue like Rosenberg; he was the calm calculator who steered chaos, whose spreadsheets decided over life and death. In his defiant cry from the gallows, we hear not only a man’s last breath, but the immortal illusion of the Reich. And in the silence that followed, the world breathed a sigh of relief and vowed that such a thing would never happen again—but history, ever vigilant, knows better.