“**THE EXECUTIONER OF BUCHENWALD**”: Martin Sommer – The man who transformed Goethe’s forest into a hillside forest where bound arms and lethal injections were the only answer to his crimes _de407

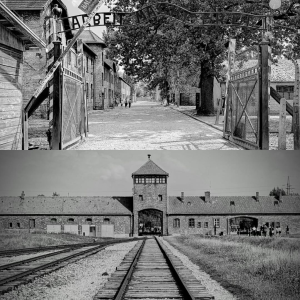

In the shadow of Weimar, the cradle of the German Enlightenment and home of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, lies the site of one of the Nazi regime’s most infamous concentration camps: Buchenwald. Built in 1937 on the Ettersberg hill, the camp owed its name – “Buchenwald” – to the natural beauty of the area, a place where Goethe himself had wandered and found inspiration. But under the Third Reich, this forest became a symbol of unimaginable horror. At the center of this development was Martin Sommer, an SS guard whose sadistic methods earned him the nickname “The Butcher of Buchenwald.” His actions not only terrorized thousands of prisoners but also horrified his own Nazi comrades, ultimately leading to his transfer from the camp. This article sheds light on Sommer’s life, his crimes, and the legacy of brutality that forever marked a landscape once associated with poetry and philosophy.

Early life and rise in the SS

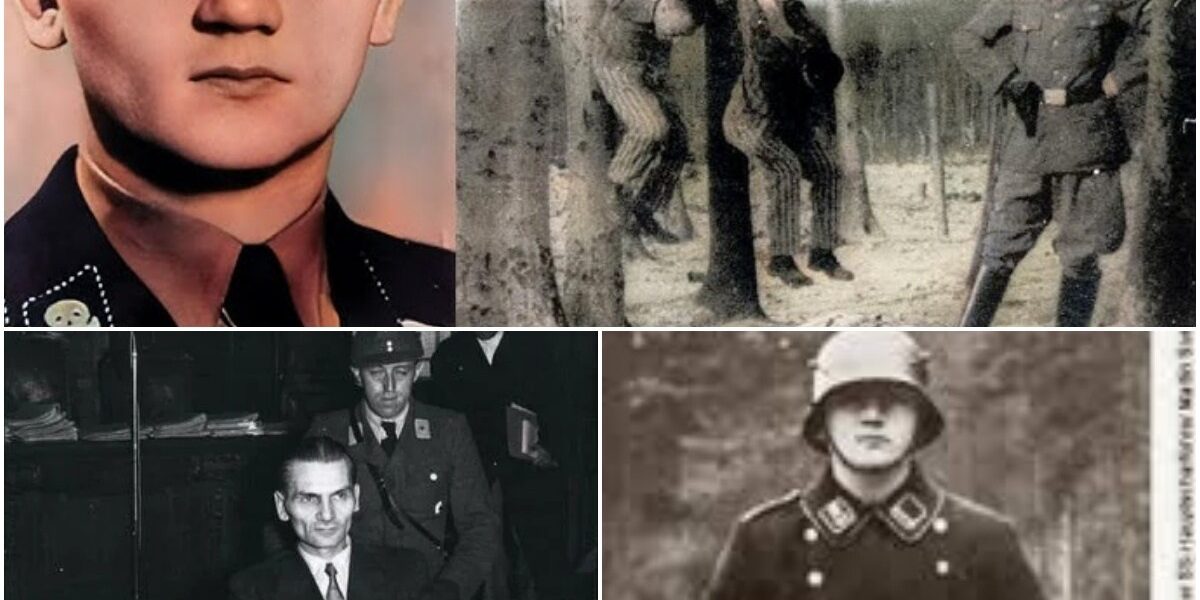

Walter Gerhard Martin Sommer was born on February 8, 1915, in Germany. Little is known about his early years, but like many young men of his generation, he fell under the spell of the Nazi Party (NSDAP) during the turbulent 1930s. He joined the Schutzstaffel (SS) and began his career in 1938 as a guard at the Dachau concentration camp. Dachau, the first Nazi concentration camp, served as a model for others, and it was here that Sommer honed his skills within the regime’s repressive apparatus.

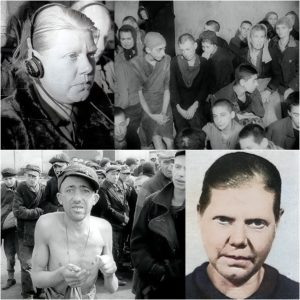

In the early 1940s, Sommer was transferred to Buchenwald, where he rose to the rank of SS-Hauptscharführer (SS Captain). He took command of the punishment block, the so-called “Bunker,” an isolated area where prisoners deemed unruly were subjected to intensified torture and isolation. Buchenwald, originally intended for political prisoners, Jehovah’s Witnesses, homosexuals, and other “undesirables,” was soon expanded during the course of the war to include Jews, Roma, and Soviet prisoners of war. At its peak, the camp housed over 100,000 prisoners, many of whom were forced into slave labor for the German war economy.

The crimes that shocked the empire

Sommer’s reign of terror in Buchenwald was characterized by a cruelty that surpassed even the already horrific standards of the concentration camp system. He earned his infamous nickname, “The Hangman of Buchenwald,” through a particularly gruesome torture method: tree hanging. Prisoners were bound at the wrists and suspended from trees in the camp’s wooded areas, their arms twisted behind their backs. This caused excruciating pain and often resulted in dislocated shoulders, permanent injuries, or death from hypothermia and exhaustion. The camp’s location in Goethe’s once-beloved Buchenwald added a bitter irony to the whole affair—Sommer transformed this idyllic forest refuge into an “executioner’s forest,” where the trees that had inspired literary greatness became instruments of torture.

One tree, the Goethe Oak, stood out amidst the horror and became a poignant symbol. It is believed that Goethe rested and conversed here during his walks. The oak was deliberately preserved during the camp’s construction, while the surrounding forest was cleared. For the SS, it embodied a perverse claim to German cultural heritage; for the prisoners, it evoked a lost world of humanism. Executions and other punishments reportedly took place near or even at this tree, although it was destroyed in an Allied bombing raid in 1944. Today, its stump, encased in concrete, serves as a memorial to the prisoners’ resilience.

Besides executions by hanging, Sommer devised other barbaric punishments. He injected prisoners with lethal substances such as carbolic acid or air to induce fatal embolisms. He sometimes hid the victims’ bodies under his bed or in secret hiding places. He forced prisoners to stand exposed to the elements for days without food or water and personally beat them to death. His prominent victims included clergymen: Sommer ordered the upside-down crucifixion of two Austrian priests, Otto Neururer and Matthias Spanlang, and beat a Catholic priest for administering sacraments. He also tortured a German pastor by hanging him naked in winter and dousing him with water until he froze to death.

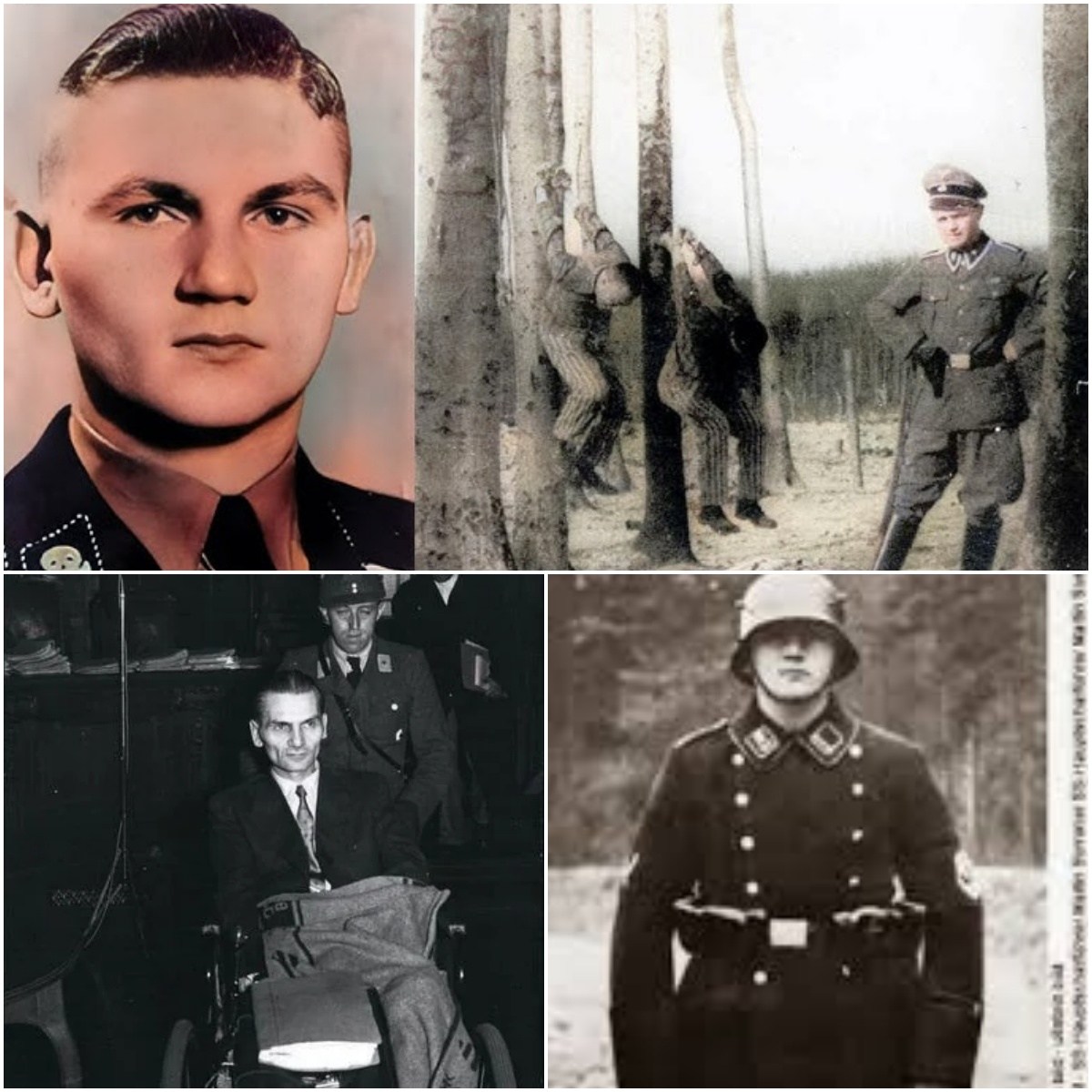

These acts were so extreme that they attracted attention even within the SS. In 1943, SS judge Georg Konrad Morgen, acting on Heinrich Himmler’s orders, investigated corruption and unauthorized killings at Buchenwald. Sommer confessed to murdering 40 to 50 prisoners, but was formally charged in only a few cases. His brutality was considered a threat to the camp’s “efficiency,” and he was transferred to a combat unit of the 9th SS Panzer Division Hohenstaufen.

War injuries and the aftermath of the war

Sommer’s frontline service was short-lived. In April 1945, he was severely wounded in an American bombing raid and lost his left arm and right leg. He was taken prisoner by the Allies, concealed his identity to avoid immediate execution, and was released in 1947 into a home for the disabled. There he lived a secluded life for a time, married, became a father, and received a disability pension.

His past caught up with him in 1950 when a former inmate recognized him, leading to his arrest. Initial charges were dropped due to his injuries, but in 1957 he was charged with aiding and abetting the deaths of 101 prisoners. In a 1958 trial in Bayreuth, Sommer was convicted of 25 counts of murder and sentenced to life imprisonment. The verdict was upheld on appeal in 1959. However, due to his deteriorating health, he was transferred to a hospital in 1971 and later to a nursing home, where he lived under certain conditions until his death on June 7, 1988.

The legacy of horror in a cultural landscape

Martin Sommer’s story is a harrowing reminder of the depths of human depravity during the Holocaust. His methods, which “shocked even other Nazis,” illustrate how the concentration camp system enabled individual sadism within the context of genocide. In Buchenwald, liberated by American troops in April 1945, over 56,000 people died of starvation, disease, medical experiments, and executions. Sommer’s crimes contributed to this high death toll and transformed a forest once celebrated in Goethe’s works—such as his reflections on nature in Faust —into a place of bound arms, lethal injections, and silent suffering.

The Buchenwald Memorial today preserves the history of the site as a memorial against totalitarianism and hatred. The stump of Goethe’s oak tree testifies to the prisoners’ hope for a better world and stands in stark contrast to the darkness perpetrated by Sommer. By commemorating figures like him, we honor the victims and reaffirm the values of humanity that the Nazis sought to destroy.