When He Weighed German POW Women, the Scale Read 72 Pounds – ‘Step Aside,’ Said the Medic

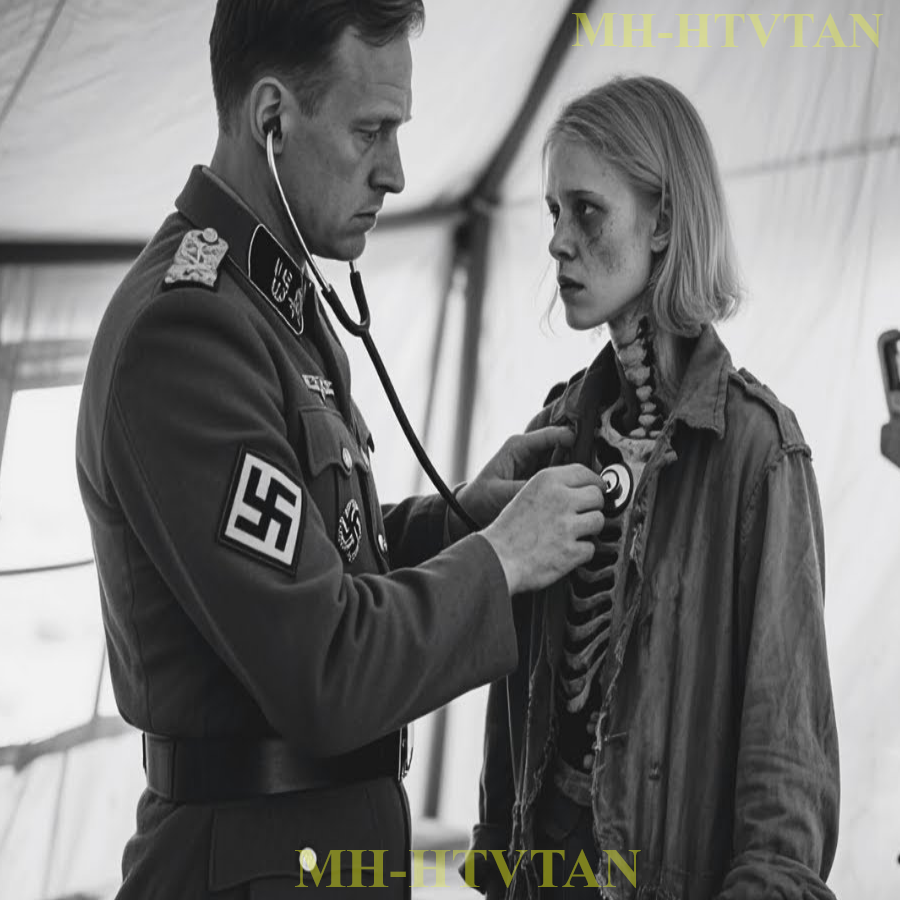

Texas, 1945. The air hung heavy over Fort Clark, thick with heat that bent the horizon into liquid. A medical tent stood near the processing center, canvas walls rippling in the breeze. And inside, Captain James Morrison pressed his stethoscope against a woman’s chest, counting heartbeats that came too fast, too weak.

The scale beside him read 72 lb. She was 19 years old. He had treated soldiers from Baton, men who’d survived death marches, and none had weighed less than this girl standing before him in a threadbear uniform that hung like a shroud. The convoy arrived at dawn, when shadows still stretched long across the desert, and the camp was just beginning to stir.

Sergeant William Hayes stood at the gates of Fort Clark, coffee cup in hand, watching the trucks roll in with their cargo of German prisoners. He expected men. Africa Corps’s veterans may be Luftvafa personnel. But when the canvas tarps lifted, women climbed down. 53 of them moving slowly, carefully as if their bones might shatter with sudden movement.

Their uniforms were vermached gray, faded to something like ash. Their faces were hollow. The war had been over in Europe for three weeks. News of victory had spread through the camp like wildfire. Men cheering, guards pouring whiskey into tin cups, radios crackling with Truman’s voice announcing surrender. But these women looked like they’d been at war longer than anyone else. They stood in formation.

Years of military discipline holding them upright despite exhaustion that carved shadows beneath their eyes. The youngest was 16, the oldest, 48. Most were in their 20s. women who’d been conscripted into auxiliary services when Germany began scraping the bottom of its manpower reserves. Hayes stepped forward, clipboard in hand, and began the intake process. Names, ranks, service numbers.

The women answered in German, voices barely above whispers. One of them, a woman who gave her name as Greta Hoffman, swayed while standing at attention. Hayes caught her before she fell, surprised by how little she weighed, how her uniform slipped loose when he helped her to a bench. She thanked him in broken English, the words coming out fractured, uncertain.

Captain Morrison arrived within the hour. The camp physician was a man who’d served in field hospitals from North Africa to Normandy, who’d sewn up wounds and amputated limbs and written letters to mothers about sons who wouldn’t come home. He’d seen starvation before. prisoners liberated from camps in Germany.

Refugees fleeing the Eastern front, but it still made something twist in his chest when he examined the first woman and found ribs like ladder rungs beneath paper thin skin. “Step aside, ladies,” he said to the nurses assisting him. “I need room to work.” The medical examinations took all day. Morrison worked through lunch, through the afternoon heat that made the tent feel like an oven, checking vitals, and making notes in neat handwriting that would later become official reports.

72 lb, 68, 81, 94. The numbers varied, but the pattern was clear. These women were dying. Malnutrition, dysentery, tuberculosis, infections that had gone untreated for months. Their teeth were loose from scurvy. Their hair fell out in clumps. Some had wounds that hadn’t healed, gashes and burns wrapped in dirty bandages that smelled of rot.

Morrison ordered immediate hospitalization for 12 of them. The others were placed on strict medical supervision, their rations carefully calibrated to prevent refeeding syndrome, a condition where starving bodies, suddenly given adequate food, go into shock. He explained this to Sergeant Hayes while washing his hands in a basin.

Water turning gray with dust and sweat. Where were they held? Morrison asked. Brittany, Hayes said. French coast. The Vermach evacuated them ahead of Allied advances. Shipped them through various camps. Looks like they spent time in a holding facility near Hamburgg before being transferred here. Hamburgg was bombed to rubble. Yes, sir.

Morrison dried his hands slowly. Hamburg had burned in 1943. Firestorms consuming the city. Temperatures hot enough to melt glass. If these women had been anywhere near those ruins, it explained some of what he was seeing. But not all of it. The systematic nature of their malnutrition suggested something more deliberate, more organized.

Rations withheld, medical care denied, women considered expendable. In the final collapse of the Third Reich, the barracks assigned to the female prisoners stood at the edge of the camp, separate from the main P compounds, where German men worked in maintenance details and messaul rotations. Fort Clark had held enemy personnel since 1942, mostly Africa Corps soldiers captured in Tunisia.

Submarine crews pulled from the Atlantic. Luftvafa pilots shot down over England. They’d settled into routines over the years, playing cards, writing letters home, working in kitchens and repair shops. Some even worked on local ranches, tending cattle under minimal guard, their presence so normalized that towns people barely noticed them anymore.

But the women were different. They moved through the camp like ghosts, silent and watchful, expecting cruelty that never quite materialized. The guards spoke to them with awkward courtesy, uncertain how to treat female prisoners. The German male PSWs stared with something like shock when they saw them during meal times.

And the American nurses, women who’d volunteered for Red Cross duty or enlisted in the Army Nurse Corps, looked at these skeletal figures and saw themselves. Lieutenant Barbara Chen was one of those nurses. Born in San Francisco to Chinese immigrants. She joined the service in 1943, served in England tending bomber crews and requested transfer to Fort Clark after VE Day to be closer to her family in California.

She wasn’t prepared for what she found in the medical ward that first evening. Women barely alive, lying in metal frame beds, breathing shallow and labored morphine for pain, Morrison told her. IV fluids when possible and watch them constantly. Some might try to refuse food, others might eat too much. Both will kill them.” Chen nodded, making notes, but her hands trembled slightly.

The woman in the nearest bed, Greta Hoffman, was watching her with eyes that held no animosity, no hatred, just exhaustion so profound it seemed to radiate from her like fever heat. “Do you speak English?” Chen asked quietly. A little, Greta whispered. You are Chinese. American, Chen said firmly. But yes, my parents came from China.

Greta closed her eyes. I have never seen Chinese person before. The conversation ended there, but it was a beginning. Over the following days, Chen and the other nurses worked 12-hour shifts, feeding patients with eyroppers when they were too weak to hold spoons, changing dressings, monitoring temperatures. The women improved slowly.

Color returned to faces. Hands stopped shaking. Some began to sit up, to speak in longer sentences, to ask questions about where they were and what would happen to them. The answer was uncertain. The war in Europe had ended, but treaties hadn’t been signed. Repatriation plans hadn’t been finalized. Germany was divided into occupation zones. Berlin a ruin.

Millions displaced and homeless. Sending these women back to that chaos felt cruel. Keeping them indefinitely felt wrong. So they remained in a kind of limbo. Prisoners who were also patients, enemies who were also victims. Sergeant Hayes found himself thinking about that distinction more than he wanted to. He’d fought in the Pacific before being reassigned stateside.

Had seen what Japanese forces did to prisoners. Had friends who died at Baton and Wake Island. He’d come home believing in clear lines, us and them, good and evil, victory and defeat. But these women complicated everything. They wore German uniforms but hadn’t chosen their service. They’d followed orders but hadn’t committed atrocities.

They’d survived horrors inflicted by their own side as much as by Allied bombs. One afternoon, Hayes was checking supply requisitions when one of the recovered prisoners approached him. Her name was Ilsa Verer, 32 years old, a former signals operator who’d served in France. She spoke better English than most of the others, having worked as a translator before the war.

Her face still looked gaunt, but her eyes had regained focus. Sharpness. Sergeant,” she said formally. “I wish to request work assignment.” Hayes looked up from his paperwork. “You’re still recovering. I am strong enough, and idleness is,” She searched for the word. “Unbearable. We sit all day. We think too much.

” He understood that the camp’s male PS had been requesting work assignments for years, not just for privileges or pay, but for the simple mercy of distraction. Men needed purpose even in captivity. Apparently women did too. What kind of work? Anything useful? Kitchen, laundry, sewing.

We are trained for support roles. Hayes made a note. I’ll bring it up with command. Thank you. She hesitated, then added, the nurses here, they are kind. This is not what we expected. What did you expect? Ilsa’s expression flickered. Revenge. The word hung between them for a moment before she saluted the crisp Vermach salute that was technically illegal now and walked away.

Hayes watched her go, thinking about news reels. He’d seen concentration camps liberated, bodies stacked like cordwood. Survivors who looked exactly like these women had looked when they arrived. The Germans had done that. these specific women, maybe not, but their country had, their military had, and yet treating them with cruelty because of that felt like becoming what they’d fought against.

Major Thomas Bradford, the camp’s commanding officer, approved work assignments for the recovered prisoners. Within a week, German women were working in the laundry facility, sorting linens, and operating industrial washers under the supervision of American personnel. Others helped in the sewing room, mending uniforms and repairing torn fabric.

A few with clerical experience were assigned to administrative work, filing papers and organizing records. The integration happened gradually, awkwardly with moments of tension and unexpected connection. American soldiers who’d lost brothers in Europe found themselves unable to look these women in the eye.

Others treated them with exaggerated courtesy, as if kindness could somehow balance the scales of war. The German male PWs watched from a distance, proud and resentful and confused, their own captivity suddenly less significant than these women who’d suffered more. Greta Hoffman recovered enough to leave the medical ward after 3 weeks.

She’d gained 16 lb, still dangerously thin, but no longer skeletal. Morrison cleared her for light duty and she was assigned to the camp library, a small room with donated books where PS could read during recreation hours. She spent her days organizing shelves, cataloging titles, occasionally recommending books to prisoners who asked for suggestions.

Lieutenant Chen visited her there one afternoon, finding Greta reading a worn copy of The Grapes of Wrath with a German English dictionary beside her. “How is it?” Chen asked, nodding at the book. Sad, Greta said simply. But beautiful, Steinbeck understands suffering. Chen sat down across from her. They’d spoken several times since that first night.

Conversations that stayed carefully neutral. Weather, health, simple observations. But something in Greta’s voice now invited deeper connection. Did you suffer? Chen asked quietly. I mean before you came here in Germany. Greta closed the book slowly. Yes, but many suffered more. I am alive. That’s not an answer. No. Greta looked at her hands, fingers still too thin, nails that had grown back riged and discolored.

We were stationed in Britany communications unit. When allies invaded, we were supposed to evacuate inland, but orders kept changing. We moved from camp to camp. Food became scarce. Medicine ran out. Some women died from illness, others from bombs. I watched my friend Margot bleed to death from shrapnel wound because we had no supplies to treat her.

She said this matterof factly as if reciting a weather report, but her hands trembled slightly against the book cover. Chen said nothing, just listened. Then we were captured by French resistance, Greta continued. They were not kind. We were German, you understand? We represented everything they hated. They kept us in a cellar for 2 weeks before Allied forces took custody.

By then, several more had died. The rest of us, she gestured vaguely at herself. Like this. I’m sorry, Chen said, and meant it. Greta looked up sharply. You should hate me. I wore that uniform. I served that regime. Did you have a choice? Does anyone? The question lingered between them, unanswerable, heavy with implications that neither wanted to fully examine.

Chen stood, preparing to leave, but Greta spoke again. Why do you treat us well, Americans? I mean, you have every reason for cruelty. Chen considered her answer carefully. Because cruelty is easy, humanity is harder, and if we become cruel, what did we win? Later that evening, Chen wrote a letter to her mother in San Francisco trying to explain what she was seeing at Fort Clark.

The words came slowly, inadequately. How could she describe the strange moral landscape of caring for former enemies? The way hatred dissolved in the face of individual suffering, the realization that war created victims on all sides, even among those who’d fought for monstrous causes. She didn’t send the letter.

Some truths were too complicated for mail. By midsummer, the German women had become part of the camp’s routine. They worked their assignments, attended medical checkups, participated in recreation hours where they played cards and wrote letters to families they hoped still existed. Some learned more English, practicing with guards and nurses who were patient with their accents.

Others remained withdrawn, locked in memories and trauma that would take years to process. The camp held a Fourth of July celebration, fireworks visible from the barracks, music drifting across the compound. Greta stood at a window, watching colored light bloom against the darkness, and thought about other fireworks she’d seen.

Tracer fire over Normandy, explosions tearing through Hamburgg, the world burning in every color of the spectrum. These were different. These were celebratory, joyful, marking independence and victory. She felt no resentment, only a strange detachment, as if watching from outside her own life. Ilsa Verer approached, carrying two cups of coffee.

Real coffee, not the Ursat Chikory they’d drunk in Germany. The Americans had luxuries that seemed impossible after years of rationing. They are happy, Elsa observed, nodding toward the Americans celebrating outside. They should be. They won and we lost. Elsa sipped her coffee. But I am glad it is over. Does that make me a traitor? Greta smiled faintly.

If so, we are all traitors. I cannot mourn the Third Reich. I can only mourn what it cost. That night, several of the women wrote in makeshift journals, recording their thoughts in German script that flowed across salvaged paper. These diaries would survive the decades, eventually donated to archives, primary sources for historians studying the war’s aftermath.

Greta wrote about the fireworks, about Lieutenant Chen’s kindness, about the strange mercy of American captivity. Ilsa wrote about guilt, not for what she’d personally done, but for what her nation had become. Another woman, Katherina Schmidt, wrote a prayer thanking God for survival and asking forgiveness for being grateful in defeat.

August brought news that Germany had formally surrendered all territories, that occupation zones were being established, that the process of denatification had begun. The male PS at Fort Clark grew restless, anxious about their futures. Would they be sent home to labor camps, tried for war crimes? The uncertainty bred tension, arguments breaking out over card games, men snapping at guards over trivial matters.

The women remained calmer, perhaps because they’d already survived worse, or perhaps because they’d internalized a different kind of resilience. They continued working, continued recovering, continued existing in the strange space between war and peace. Captain Morrison conducted final medical examinations in September, noting improvements with professional satisfaction.

The woman, who’d weighed 72 lbs, now registered at 96, still underweight, but alive, functional, healing. Others showed similar progress. The tuberculosis cases had stabilized. Infections had cleared. Hair was growing back. Teeth had been treated. Bodies had remembered how to hold nutrients and convert them to strength.

“You’ve done well,” Morrison told Lieutenant Chen, reviewing charts in his office. “These women should have died. Most would have, without proper care.” Chen nodded, accepting the praise, but feeling strange about it. They’d simply treated patients, done their jobs. The fact that it felt remarkable that showing basic medical competence to former enemies seemed extraordinary said something troubling about how war twisted human nature. In October, orders came through.

The German women would be repatriated in November, transported to Bremen, and placed in displaced persons camps until permanent housing could be arranged. The news was met with mixed reactions. relief that captivity was ending, fear of what they’d find in Germany, uncertainty about families, homes, futures in a destroyed nation.

Greta received the notification during her shift at the library. She read it twice, then carefully set it aside and continued shelving books as if normal routine could hold back the approaching change. Lieutenant Chen found her there an hour later, still working, moving with mechanical precision.

“You heard?” Chen asked. Yes. Are you afraid? Greta placed another book on the shelf. Moby Dick. Spine cracked from repeated readings. I do not know what I am. Germany is rubble. My city Dresden is gone. My family. She didn’t finish the sentence. Chen moved closer. I’m sorry we couldn’t keep you here longer. Get you fully recovered.

You saved my life, Greta said simply. That is enough. They stood in silence for a moment. Two women whose paths had crossed because of war, whose connection existed only in this temporary space between combat and aftermath. In another world, they might have been friends, colleagues, neighbors. In this one, they were nurse and patient, victor, and vanquished American and German.

Labels that meant everything and nothing. The final weeks passed quickly. The women prepared for departure, gathering meager possessions, donated clothing, personal items, photographs taken at the camp that showed them smiling, healthy, alive. Some wrote letters to the nurses and guards who’ treated them well, expressing gratitude and careful English.

Others remained silent, locked in anticipation or dread. Sergeant Hayes organized a small farewell gathering. Nothing formal, just coffee and donated pastries in the messaul. Several guards attended along with medical staff. The German women came in civilian clothes provided by the Red Cross, dresses and blouses that hung loose but were clean, respectable.

They looked like normal women again, not prisoners, not soldiers, just people preparing for an uncertain journey. Ilsa Verer approached Hayes, extending her hand in the American style rather than saluting. He shook it, surprised by the firmness of her grip. Thank you, she said, for treating us as human. Hayes nodded, uncomfortable with gratitude he wasn’t sure he deserved. Good luck.

I hope you find your family. And I hope, Elsa said carefully, that you never forget we were your enemies, but also that we were women. Both things can be true. She walked away before he could respond, rejoining the other women who were preparing to leave. Hayes stood watching them, thinking about the strange mathematics of war.

How millions died while individuals survived. How hatred could be both justified and insufficient. How mercy didn’t erase crimes but might prevent future ones. The convoy departed on November 12th, trucks rolling out at dawn just as they’d arrived 7 months earlier. But the women who climbed aboard now were different from the skeletal figures who’d arrived.

They were still thin, still marked by trauma, but they moved with strength, with purpose, with the resilience that comes from surviving impossible things. Greta sat near the rear of the truck, watching Fort Clark recede in the distance. She thought about the medical tent where Captain Morrison had first weighed her, the library where she’d read Steinbeck, the window where she’d watched Fourth of July fireworks bloom in the darkness.

She thought about Lieutenant Chen’s quiet kindness, Sergeant Hayes’s awkward courtesy, the strange mercy of American captivity that had allowed her to remember she was human. She would return to Germany, to ruins and occupation, and an uncertain future. She would search for her family, find only partial answers, eventually rebuild a life in the wreckage of the Reich.

But she would carry with her the memory of this place. This unexpected mercy. This proof that even in war’s aftermath, humanity could survive if people chose to protect it. The trucks rolled through Texas desert. Dust rising behind them like memory itself. Visible, then fading, then gone, but not forgotten.

Never entirely forgotten. 53 women entered Fort Clark weighing an average of 84 lb. They departed weighing an average of 118. 12 had been near death. All 12 survived. The camp’s medical records would later become primary sources for studies on starvation recovery and trauma treatment. Captain Morrison published a paper in 1947 detailing his protocols, helping inform care for displaced persons throughout Europe.

Lieutenant Barbara Chen continued serving in military medicine until 1948. then returned to California and became a psychiatrist specializing in trauma. She never spoke publicly about the German prisoners she’d treated, but she kept Greta Hoffman’s photograph in her desk drawer until she died in 1993. Greta returned to Dresden, found her mother alive, but her father and brother dead, and worked as a librarian for 37 years.

She corresponded with Chen until 1967, letters that discussed books and weather and carefully avoided discussing the war. She died in 1989, months before the Berlin Wall fell, leaving behind journals that documented her time at Fort Clark with literary precision. The camp itself closed in 1946, converted to a seminary, then a museum.

The barracks where the women lived were torn down in the 1950s, replaced by parking lots and administrative buildings. Nothing physical remains of their presence except photographs and records. Women in borrowed dresses smiling tentatively at cameras. Alive despite every expectation, 72 lb. That’s what the scale read when Captain Morrison first examined Greta Hoffman in May 1945.

By November, she weighed enough to stand, to work, to hope. The difference, that addition of weight and health and humanity, represented something larger than medical treatment. It represented a choice made daily by guards and nurses and commanding officers, to see enemies as people, to treat prisoners as patients, to preserve life even when revenge might have felt justified.

History remembers wars through battles and leaders, strategies and casualties, but it should also remember moments like these. Not because they redeem wars horrors, but because they prove that even in war’s aftermath, even between former enemies, mercy remains possible if people have the courage to choose it.

The scale read 72 lb, then 96, then more. Each pound represented survival, recovery, the stubborn human capacity to heal even from wounds that should have been fatal. Captain Morrison recorded those numbers in neat handwriting, clinical and precise. But beneath the data was a story about choice. The choice to care, to heal, to remember that enemy soldiers were also human beings worthy of basic dignity.

That choice mattered. It still matters as long as anyone remembers the scale reading 72 lb and remembers what came