THE SHAMEFUL END: The Mass Execution of Nazi Generals and Officers Hanged for Killing Millions in Belarus _us

The Minsk Trial of 1946 stands as a significant moment in the aftermath of World War II, bringing justice to those responsible for devastating atrocities in Belarus. Following the German occupation, which resulted in immense suffering and loss of life, Soviet authorities held 18 Nazi officers accountable for their roles in war crimes. Conducted in Minsk, the capital of Soviet Belarus, this trial addressed the horrors inflicted on the region, ensuring that the perpetrators faced consequences. This analysis, crafted for history enthusiasts and readers on platforms like Facebook, explores the historical context of the occupation, the trial’s proceedings, and its lasting impact, presenting a thoughtful reflection on justice and remembrance in a way that respects the sensitivity of the topic.

The German Occupation of Belarus

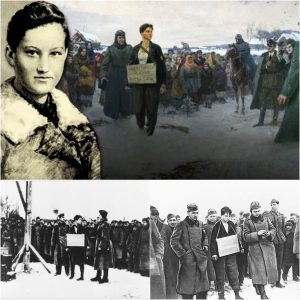

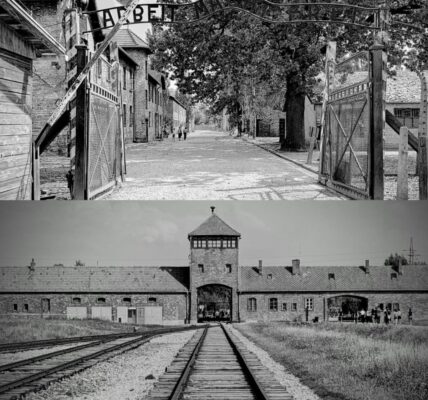

On June 22, 1941, Nazi Germany launched a massive invasion of the Soviet Union, targeting Belarus with devastating force. By June 28, Minsk was captured, marking the beginning of a brutal occupation. The Nazis implemented policies aimed at suppressing the local population, particularly targeting Jewish communities. On July 3, 1941, approximately 2,000 Jewish intellectuals were executed in a forest near Minsk, a tragic act intended to weaken the cultural fabric of Belarusian society.

Under orders from Reinhard Heydrich, head of the Reich Security Main Office, the persecution escalated. By August, Nazi policies expanded to target Jewish women, children, and the elderly, leading to widespread loss of life. Specialized units, including the Einsatzgruppen and collaborating police forces, carried out these acts in areas near ghettos, often using mass graves or gas vans. In late July 1941, the Minsk Ghetto was established, confining around 80,000 Jews from Minsk and nearby areas in dire conditions. Between November 1941 and October 1942, nearly 24,000 Jews from Germany, Austria, and Bohemia-Moravia were deported to Minsk, with many facing immediate execution at Maly Trostinets, a site eight miles east of the city. Those who survived were segregated in a separate ghetto section, isolated from local Belarusian Jews.

The occupation left Belarus with profound losses, with estimates suggesting over two million lives were lost, including 500,000 to 550,000 Jews, alongside the destruction of thousands of villages. This period remains one of the darkest in Belarusian history, underscoring the need for accountability.

The Minsk Trial: A Pursuit of Justice

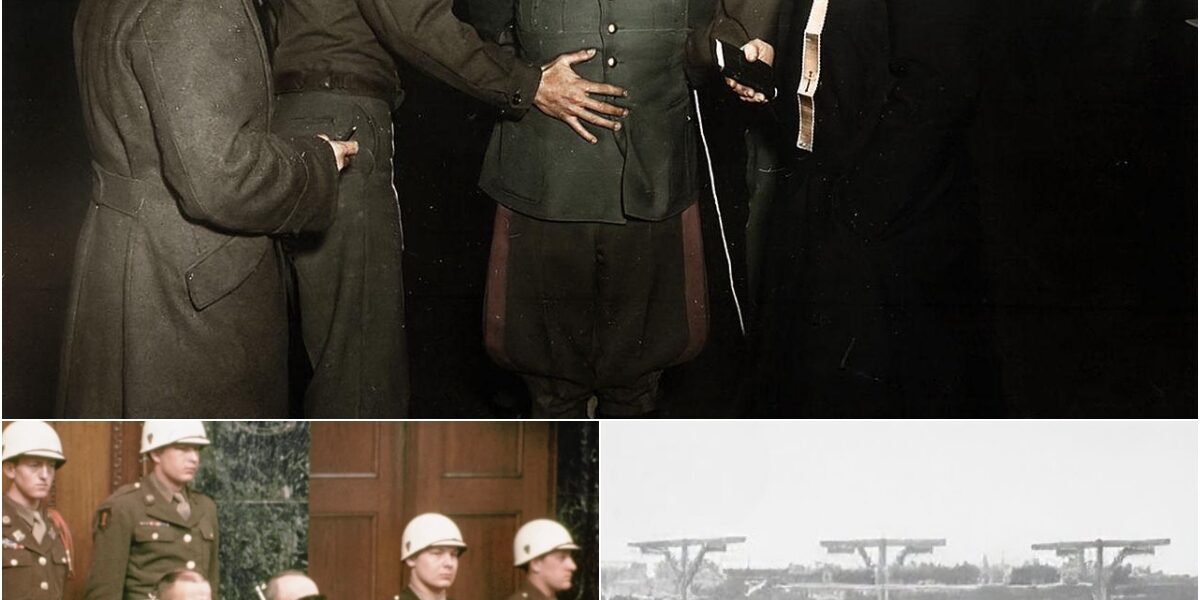

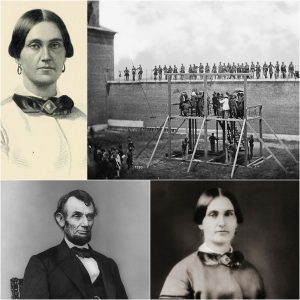

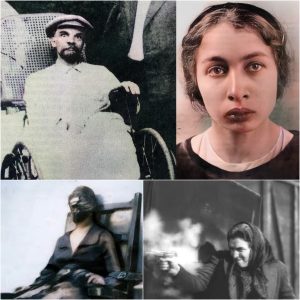

Following the liberation of Belarus by the Red Army in 1944, Soviet authorities began investigating the extent of Nazi atrocities. The Minsk Trial, held from December 1945 to January 1946 at the Red Army House, brought 18 German military personnel to justice. The defendants included 11 Wehrmacht members, such as generals Johann-Georg Richert and Gottfried von Erdmannsdorff, four Order Police officers, and three members of the Waffen-SS and SD. These individuals were linked to policies and actions that caused immense suffering, including the destruction of villages and the operation of the Minsk Ghetto.

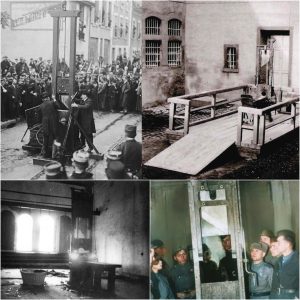

The trial relied on survivor testimonies, confessions, and documented evidence to detail the scale of the crimes. Witnesses recounted the devastating impact of mass executions and ghetto conditions, providing a clear picture of the occupation’s brutality. The tribunal, conducted by a Soviet military court, aimed to hold those responsible accountable, focusing on their roles in orchestrating or executing orders that led to widespread harm. On January 29, 1946, the court delivered its verdicts at Minsk’s horse racing venue: 16 defendants were sentenced to death, while two received lengthy labor sentences due to their lesser roles. The trial highlighted the involvement of various Nazi units, including the Wehrmacht, challenging narratives that limited responsibility to the SS.

The Outcome and Its Significance

The sentences were carried out shortly after the trial, with the 16 condemned defendants executed publicly in Minsk. These executions served as a moment of closure for a region scarred by years of occupation, offering a sense of justice to survivors and communities. The public nature of the proceedings allowed Belarusians to witness accountability for the suffering endured, reinforcing the importance of confronting war crimes.

The Minsk Trial, while less known than the Nuremberg Trials, played a crucial role in documenting the atrocities committed on the Eastern Front. It provided a platform for survivors to share their experiences and ensured that the historical record reflected the scale of Nazi crimes in Belarus. However, some historians, such as Manfred Zeidler in his 2004 study, have noted that the trial’s reliance on confessions—some possibly coerced—raises questions about its methods. Despite these concerns, the trial’s contribution to justice and remembrance remains significant, offering a framework for understanding the occupation’s impact.

A Lasting Legacy

The Minsk Trial’s legacy lies in its effort to address the immense suffering caused by Nazi policies in Belarus. By holding high-ranking officers accountable, it underscored the importance of confronting those who enable or perpetrate atrocities. The trial also highlighted the resilience of survivors, whose testimonies brought the truth to light. For modern audiences, the trial serves as a reminder of the consequences of unchecked power and the need to preserve historical memory.

The Minsk Trial of 1946 was a pivotal moment in Belarus’s journey toward healing, holding 18 Nazi war criminals accountable for their roles in the region’s suffering. From the horrors of the Minsk Ghetto to the mass executions at Maly Trostinets, the trial exposed the devastating impact of the German occupation. For readers on platforms like Facebook, this story offers a compelling look at justice in the face of unimaginable loss, encouraging reflection on the importance of accountability and remembrance. The Minsk Trial reminds us to honor the memory of the millions affected by Nazi atrocities and to remain vigilant against hatred, ensuring that history’s lessons guide us toward a more just future.