American Medic Delivers German Woman’s Baby During Battle — Her Reaction Shocked Him-Mex

The walls are screaming, not metaphorically. The stone foundation of the half-colapsed farmhouse shrieks as another shell lands 50 meters away. And Rosa, his becker, his hands clench around the medic, his wrist hard enough to leave marks. Her fingernails draw blood. She does not notice. Corporal James Hayes does not pull away.

I cannot, she gasps in broken English. Please, I cannot. You can. His voice is steady. impossibly steady as the ceiling showers them with plaster dust. You are doing this right now with me. The foxhole smells of wet earth and cordite, of blood and fear. Rosa can taste copper on her tongue.

Can feel the November cold biting through her soaked dress. Her body is doing things beyond her control, tightening, releasing, preparing for something that should happen in a warm bed with a midwife. His gentle hands not here in this hole in the ground with death reigning from above. Rosa, his mind locks on a single thought.

An American soldier has his hands inside me while his artillery kills my neighbors. The absurdity nearly makes her laugh. 3 days ago, she watched Frowholer his house disintegrate in a direct hit. Two days ago, she buried what was left of her husband, Carl. Yesterday she was running through the Werkin forest, 9 months pregnant, trying to reach safety before the Americans overran her village.

She did not make it. Now this boy, because that is what he is, a boy with Tennessee vowels and hands that will not stop shaking, is delivering her baby in a foxhole while the battle of Horton Forest rages above their heads. Why? She manages between contractions. Why? Help me. Hayes does not answer.

His face is pale in the dim light. He is 22 years old, trained to patch holes in soldiers, not bring new life into a world that is trying its hardest to end it. His hands move with mechanical precision, following half-remembered training he was never supposed to use. The artillery has a rhythm 3 seconds between impacts, then five, then two.

Rosa counts without meaning to. Her body tightening with each crash, unable to tell the difference anymore between contractions and explosions. The baby is crowning, Hayes says in his voice cracks on the second word. Above them, through the hole in the roof, Rosa can see smoke rising black against November gray. The village is dying. Germany is dying.

She is dying probably because women die doing this, even in hospitals. And this is a foxhole with a terrified American medic who learned obstetrics from a single lecture. But he is still here. His hands are still steady. And when the next contraction hits, Rosa Becker pushes. 6 months earlier, Rosa had received a letter from Carl on the Eastern Front that made her hands shake.

“The Americans will shoot you on site if the lines collapse,” he had written. “I have seen what they do. This is not propaganda, Lee. Run if they come.” Carl had never lied to her. not once in their three years of marriage. If he believed this, it must be true. The propaganda reinforced everything.

Posters across Bergstein showed American soldiers as monsters. “This is the face of your liberator,” one read, showing exaggerated, threatening features. Another depicted bombed hospitals with dead children. “American precision bombing of civilian targets.” Rosa, his mother, remembered the Great War blockade.

children starving while British admirals sipped tea. “They starved us then,” Ingrid said. “They will do worse now.” By November 1944, Rosa was 9 months pregnant, and Carl was dead. The Americans were 3 km away. She could hear their artillery at night, walking closer each day. The village was evacuating, but she had waited too long.

Labor could start any hour, and travel was impossible. Her mother left with the last wagon convoy. Rosa stood in the doorway, one hand on her belly, watching the road disappear into the forest. Perhaps 50 civilians remained the old, the stubborn, the afraid. The Americans came on November 16th.

Rosa was in the cellar when she heard the tanks, the grinding of treads on cobblestone, rifle fire, shouting in English, harsh and incomprehensible. She pressed herself against the stone wall, hands over her belly, and prayed, “They will kill me. They will kill my baby. This is how it ends.” The fighting lasted 3 hours. Then silence.

Rosa stayed in the cellar for 2 days. She had water, a little bread, no way to start a fire. The temperature dropped. November cold seeped through the stone as she wrapped herself in blankets, feeling her baby kick. On the third day, the contraction started. The first contraction was a lie. Rosa felt the tightening and thought, “Not yet.

Not now, not here.” The second contraction, 15 minutes later, shattered that delusion. She was alone in a cellar in occupied territory. No midwife, no mother, no Carl. If she screamed, the Americans would find her. And then they would do what Americans do. The contractions came faster. 20 minutes apart, 15 10.

By the third hour, when they hit every 5 minutes with the force of something tearing her in half, she could not keep quiet anymore. The first scream escaped without permission. The cellar door opened 30 seconds later. Rosa, his hand, found the kitchen knife she had kept beside her, dull, useless, but something. She raised it with shaking hands as boots descended the stairs.

“American boots?” “Do not,” she gasped in German. “Do not touch me.” The soldier froze. He was young, terrifyingly young, with a medic, his armband, and a face that belonged in a classroom, not a war zone. He raised both hands, showing empty palms. “Easy,” he said in English. Then, in terrible German, Nick Chason, no shooting, I help a trick. This is a trick.

Another contraction hit like artillery. The knife clattered from Rosa, his hand. She doubled over. And when she looked up again, the American was kneeling beside her. Not grabbing, not forcing, kneeling. His hands hovering uncertainly, asking permission with his eyes. “Baby,” he said, pointing at her belly.

“Baby coming?” Rosa forced the words out in English. “Yes, baby. now. Okay. He nodded too quickly, his fear obvious. Okay, I help. I am medic James. My name is James. James Yakob. Almost a German name. He was fumbling with his medical kit, pulling out supplies that were not meant for this. Bandages, sulfa powder, morphine, nothing remotely appropriate for delivering a baby.

He looked at the contents with something approaching panic. Have you done this? She asked. No, he admitted. Never. Something in her chest loosened slightly. Because he could have lied. Could have pretended competence. Instead, he was honest. This enemy soldier with his terrible German and shaking hands. We do it together.

Rosa heard herself say. Yes. Yes. James agreed. The artillery started 20 minutes later. Not small arms fire. the deep earthshaking thunder of German 88s firing from the forest. The Americans responded immediately. 105 mm howitzers that made the cellar walls shake and dust rain from the ceiling. We have to move, James shouted.

This building, it is not safe. I cannot move. But James was already lifting her one arm around her shoulders, supporting her weight as he guided her up the cellar stairs. Her legs were moving somehow, and he was supporting her. And then they were outside in the November cold. The village was unrecognizable. Houses that had stood for centuries were rubble.

The church steeple was gone, replaced by a jagged tooth of stone. American soldiers were taking cover, shouting orders, returning fire. James half carried Rosa toward what had been a farmhouse. The roof was partially collapsed, but three walls still stood, and there was a foxhole dug deep enough to provide cover.

He lowered her into it, then jumped in after her. The world above them was ending. The world below was beginning. “How close?” James asked, his hands checking her pulse, falling back on the training he actually had. “Close,” Rosa managed. “Very close. I feel I need to push.” “This is insane. You do not deliver babies in foxholes during artillery bargages.

” But it was happening. The contractions were 90 seconds apart now. Each one drowning out even the artillery. Rosa, his body, had made its decision. The baby was coming here. Now, whether the war allowed it or not, James positioned himself at Rosa, his feet. His hands were shaking so badly he had to clench them twice before they steadied.

He had had one lecture on emergency childbirth. One, the instructor had said they would never need it. Rosa saw the terror in his face and felt something unexpected. Pity. This boy was about to do something he was completely unprepared for. And he was doing it anyway. Not because he had to, because she needed help. Between contractions, in a moment of strange clarity, Rosa noticed details.

The freckles across James, his nose, the way his atom, his apple bobbed when he swallowed. The wedding ring missing from his finger. too young to be married, probably. Or maybe he had taken it off before deploying, afraid of losing it in the mud and chaos of war. “Do you have family?” she asked suddenly.

“Brothers, sisters?” James looked startled by the question. “Two sisters, younger Mary and Elizabeth. You think of them when you are scared?” “Always,” he admitted. His hands steadied slightly. I think about getting home to them, about teaching Mary to drive, about walking Elizabeth down the aisle someday.

Rosa understood then this was not just duty. He was thinking of his sisters, thinking that if they were trapped in a cellar, terrified and alone, he would want someone to help them, even an enemy. Why? She asked again. You could leave. Say you found me dead. No one would blame you. James looked up. His eyes met hers.

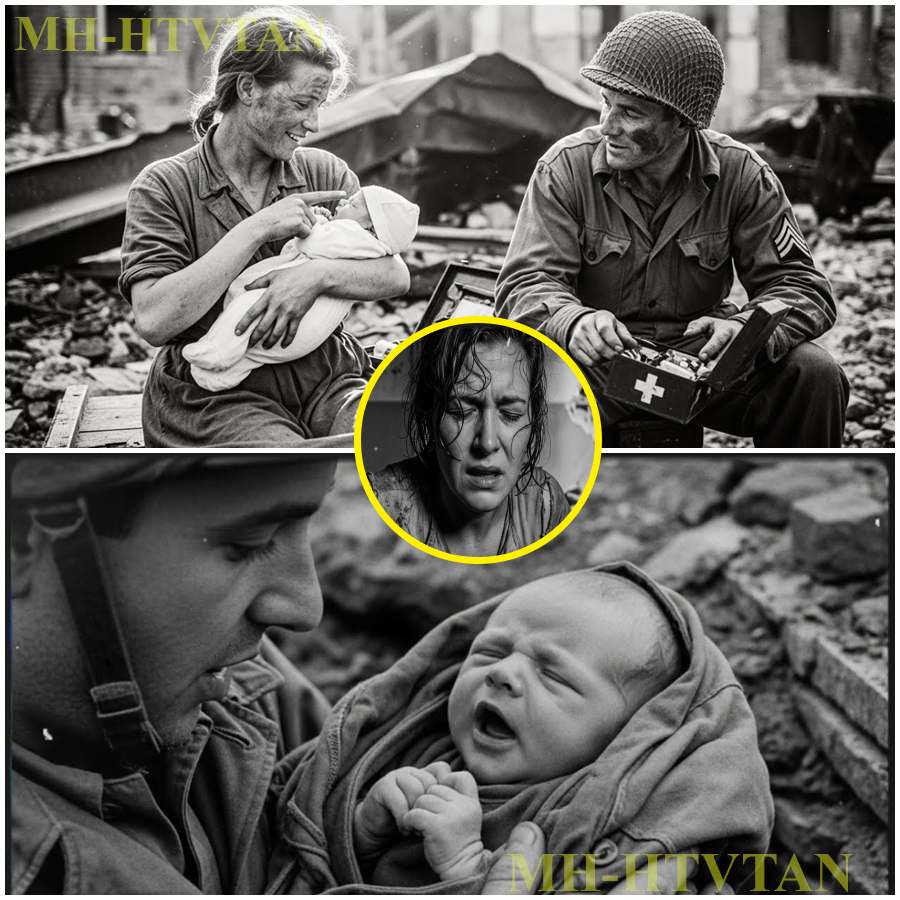

And there was something in them that reminded her of Carl. The same stubborn decency. Because I am a medic, James said simply. It is what I do. Another shell landed. Closer. Close enough that dirt rained into the foxhole. Rosa tasted earth and blood and fear. Push, James said. Rosa, push now. She did. The baby crowned during a lull in the shelling.

Rosa would remember this forever. the strange stillness. 5 seconds were the artillery paused like God taking a breath. And in that impossible silence, James Hayes said, “I see the head. Oh God, I see the head.” His voice cracked with wonder. “Not fear anymore.” “Wonder. One more,” he urged. “Rosa, one more.” She gathered everything left all her strength, all her determination, all the stubborn refusal to die that had carried her this far, and pushed with every fiber of her being.

The baby slid free into James his waiting hands. For a moment there was no sound, not from the baby, not from the battlefield. Rosa, his heart stopped. Then a whale, high and indignant and furiously alive. James was laughing, crying and laughing simultaneously, holding this tiny human like it was made of glass.

“It is a boy,” he said, voice thick with emotion. “Rosa, you have a son.” He wrapped the baby in his own jacket, his field jacket, US Army issue, with his name stencled on the front and placed the bundle in Rosa, his arms. The baby was red and wrinkled and furious, his tiny fist waving at the injustice of being born into a war zone.

He was perfect. Rosa looked down at her son, then up at the American medic who had just delivered him, and felt her entire understanding of the world tilt sideways. This was not how it was supposed to go. Americans were monsters, invaders. The enemy who would show no mercy. But James was cutting the umbilical cord with a sterilized knife.

his hands gentle and precise. He was making sure Rosa was comfortable. He was treating her like a person, like someone who mattered. Why? The artillery resumed. But in this foxhole, for this moment, there was peace. James was checking the baby, his breathing, counting heartbeats with his fingers on the tiny chest.

He is strong, he said. He is going to be fine. His name, Rosa said suddenly. The words came without thought. YaKob. His name is Jacob. James looked up confused. Jacob. It is German for James like you. She watched understanding dawn on his face. This baby born in a foxhole while their countries tried to kill each other would carry this American.

His name would be a walking testament to one moment when the war did not win. James opened his mouth, closed it, tried again. I do not know what to say. Say you will help me reach hospital, Rosa replied. Say you will make sure my son lives. I will, James promised. I swear to God I will. The American aid station was 3 km away through active combat, through streets where every corner might hide a sniper, through a forest where artillery had turned trees into splinters.

James made the journey four times that day. First, he went alone to find help. He returned with a stretcher and another medic, a sergeant named Patterson, who took one look at Rosa and the baby and whistled low. “Jesus Christ, Hayes, you delivered a baby in a foxhole.” Apparently, James said, his hands shaking again now that the adrenaline was fading.

They carried Rosa through the village as carefully as the situation allowed. Every hundred meters, they stopped to take cover. When Yakob started crying, Patterson pulled a chocolate bar from his rations and broke off a piece, letting it melt in Rosa his mouth. For energy, he explained gruffly. “Baby needs you strong.

” Rosa stared at him. “American chocolate given freely.” She had been told Americans hoarded supplies let civilians starve. But here was this sergeant sharing his rations without being asked. At the aid station, the doctors were overwhelmed. The battle of work and forest was producing casualties faster than they could process them.

The tent was organized by triage, immediate, delayed, expectant. Rosa watched men die while waiting for surgery. When her turn came, the chief medical officer examined her efficiently. “You and the baby are stable,” Captain Morrison concluded. “But you need rest, proper nutrition, somewhere warm.” “Where?” Rosa asked. My house is destroyed.

Morrison looked at James who was hovering nearby. Hayes, what is the status of the displaced person’s facility? Full, sir, overflowing. Find her a spot anyway. Special circumstances. And Hayes, good work. That baby would not have made it without you. After Morrison moved on, James stayed. Rosa expected him to leave. His duty was done.

But he remained by her cot, checking on YaKob, bringing her water, finding a clean blanket. “You should go,” Rosa said. “You have other wounded. They will manage without me for an hour.” It was not professional responsibility. They both knew it. This was something else, some connection forged in that foxhole that neither knew how to name.

Rosa found herself talking. Maybe it was exhaustion. Maybe she needed to fill the silence. She told him about Carl, about the letter warning her to run, about the propaganda and her mother, his fear, and her own terror in that cellar. I thought you would kill me, she admitted. I thought all Americans were the things we were told.

James was quiet for a long moment. We were told things about Germans, too, he said finally. About how you all worshiped Hitler, how you all wanted this war. And now James looked at YaKob sleeping in Rosa his arms. Now I do not know what to believe anymore. James visited three times in the next week, always officially checking YaKob his weight, examining Rosa his recovery, bringing vitamins from medical supplies.

But he had lingered afterward, asking about her life before the war, telling her about Tennessee, about his family, his tobacco farm. At the end of November, James brought news. Rosa and Jacob were being transferred to a larger displaced person’s camp near Doran where conditions were better, more food, actual medical facilities.

When? Rosa asked. Tomorrow. I am sorry. I know it is sudden. Rosa looked around the crowded tent at the other displaced persons wearing their fear like a second skin. At the American soldiers moving among them with casual efficiency. She thought about the journey that had brought her here. The terror in the cellar. The foxhole delivery.

The moment James had placed YaKob in her arms. I need to tell you something, she said. Before I go in the cellar when you found me, I had a knife. I was going to use it. I saw the knife, James said quietly. You saw it and you helped me anyway. You were in labor. What was I supposed to do? Walk away. Report it. Let me die.

Any of those would have been easier. James was quiet when he spoke. His voice was careful. My first week here, we captured a German soldier, 18 years old, Hitler youth, hit by shrapnel. He was crying for his mother. Literally crying in German. Rosa waited. I gave him morphine, patched him up, and he ended up telling us where his unit was planning an ambush.

Probably saved 20 American lives because I treated him like a person. Rosa understood. Because you were kind to him. Because kindness matters, James corrected. Even in war, especially in war. Yakob woke, his tiny face scrunching with displeasure. Rosa adjusted him, let him nurse, and felt the familiar pull of exhaustion.

Four weeks old now. Four weeks of survival against impossible odds. I do not know how to thank you, she said finally. Do not thank me. Just take care of Jacob. Make sure he knows that people can be decent even in the worst circumstances. That is enough. But it was not enough. This man had given her something immeasurably precious.

Not just her son his life. He had given her hope. Proof that the propaganda was lies. Evidence that mercy still existed in a world designed to stamp it out. Before he left, James pressed something into her hand. Dog tags. his dog tags for after the war, he explained. So you can find me if you want to. Rosa closed her fingers around the metal.

It was warm from his skin. I will want to, she promised. Yakob should know the man who delivered him. James smiled, a real smile. The first she had seen that was not tinged with fear. I would like that. The next morning, Rosa and a group of displaced persons were loaded onto a truck bound for Darren. James had been called away.

Another emergency, another wounded soldier who needed saving. She held Jacob close as the truck pulled away, watching the aid station disappear behind them. In her pocket, the dog tags pressed against her hip like a promise. Rosa did not see James Hayes again for 60 years. After the war, she spent months trying to find him.

She wrote letters to the US Army Medical Corps. She contacted the Red Cross. She showed the dog tags to every American official she encountered. The responses were always the same. We cannot locate Corporal James Hayes. Records from the Hortan Forest engagement are incomplete due to high casualties and difficult battlefield conditions.

Eventually, Rosa stopped searching. She had a son to raise in a devastated country. She found work in Dusseldorf. She remarried in 1949 a good man named Ernst Mueller who accepted Jacob as his own, but she kept the dog tags. And she told Jacob the story, not the sanitized version, the real one.

About the knife in the cellar, about the foxhole delivery, about an American medic who could have walked away and did not. Jacob became a history teacher specializing in the post-war period and how former enemies became allies. His students heard the story of his birth every semester, not as propaganda, but as evidence that individual actions matter, that choices compound, that mercy is never wasted.

In 2004, Yakob, his daughter Anna, decided to find the American medic who delivered her father. She had advantages Rosa never had. The internet, digitized military records, genealogy websites. It took her three months. James Hayes lived in Knoxville, Tennessee. He was 82 years old.

He had returned home after the war, gone to college on the GI Bill, become a family doctor. He had delivered hundreds of babies in his 40-year career. But he had never forgotten the first one. They met at a coffee shop on a warm September afternoon. Yakob saw an elderly man by the window, weathered but kind, and something in those eyes was unmistakable. “Dr. Hayes? Anna asked.

This is my father, YaKob Becker, though you knew his mother as Rosa. James, his coffee mug, hit the table with a clatter. He stared at YaKob with an intensity that might have been uncomfortable if it was not so obviously emotional. Rosa, his son, he whispered. The baby from the foxhole. He was crying, not quiet, tears full, shaking sobs. YaKob found himself crying too.

And then they were embracing. Two men who had never met but who were connected by the most intimate of bonds. I did not know if you made it, James said, pulling back. After you were transferred, records were chaos and I was shipped to the Pacific. And then I came home and tried to forget.

He paused, wiping his eyes. But I never could forget. Not really. Some nights I would wake up and hear the artillery, feel the weight of you in my hands, wonder if you survived. If your mother survived, if it meant anything. It meant everything. YaKob said, “We made it because of you. My mother told me the story my entire life. She never forgot you.

” He pulled something from his pocket. She kept your dog tags. Carried them until she died in 1998. James, his hand shook as YaKob placed the tags in his palm. The metal was worn smooth by decades of Rosa his touch. “I have something for you, too,” James said. He pulled a photograph from his wallet, creased and faded.

Rosa in the displaced person’s facility holding newborn YaKob exhausted and radiant. Patterson took this before you were transferred. I have carried it every day since. They stayed for 3 hours. Before they parted, YaKob introduced his children. This is the man who delivered me in a war zone, he told them. The man who proved that even in the darkest moments, people can choose kindness.

James Hayes died in 2011 at age 89. YaKob was with him at the end, holding the hand that had once delivered him while shells fell. At the funeral, YaKob gave the eulogy to 200 people in a Tennessee church. He told the story one final time. The seller, the foxhole, the impossible delivery. I exist, YaKob concluded, because one person chose compassion over convenience.

Because one medic decided that a woman in labor was a person first and an enemy second. Because James Hayes believed that life is sacred even in war, especially in war. Today, Yakab Becker is 79 years old. He teaches history at the University of Bon, specializing in post-war reconciliation. His students still hear the story of his birth, not as ancient history, but as proof that the choices we make in extreme circumstances reveal who we really are.

In his office hangs a photograph. James Hayes in his Army medic uniform, young and uncertain. Next to it, James at 88, surrounded by Yakob, his family, laughing. Between the photographs, mounted in a simple frame, dog tags stamped with the name James F. Hayes, worn smooth by a German mother, his touch carried across decades as a reminder of what is possible when we refuse to let hate define us.

Yakob sometimes runs his fingers over the metal, feeling the same worn grooves his mother once traced. He thinks about the knife in the cellar, about the foxhole delivery, about an American boy who had every reason to walk away and did not. He thinks about how his mother named him after an enemy who became a savior and how that name YaKob, German for James, became a bridge between worlds that should have stayed separate forever but did not.

Because one person on one impossible day made one impossible choice and changed everything. Thanks for watching. I hope this story from the past intrigued you. Do not forget to like, share, and subscribe for more historical tales.