Mxc- It Was Just an Old Photo of WWII — Until Researchers Deciphered the Message in Their Hands

It was just an old photo of propo katus until researchers deciphered the message in their hands. The photograph surfaced in the archives of the Virginia Historical Society in the fall of 2019. It had been donated years earlier as part of a larger collection of World War II memorabilia cataloged simply as military group portrait Camp Lee Virginia 1943 and filed away in a climate controlled storage room where thousands of similar images waited in silent obscurity.

Dr.Jerome Patterson, a military historian specializing in the segregated armed forces, was conducting research for a book on African-American soldiers during World War II when he requested access to the society’s photographic archives. He had seen hundreds of such images before, formal military portraits, training exercises, deployment ceremonies.

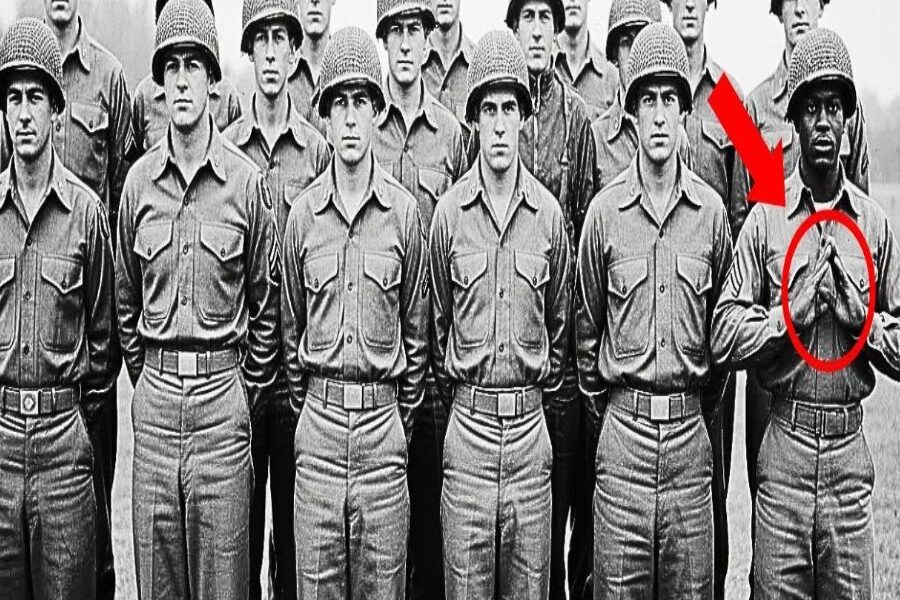

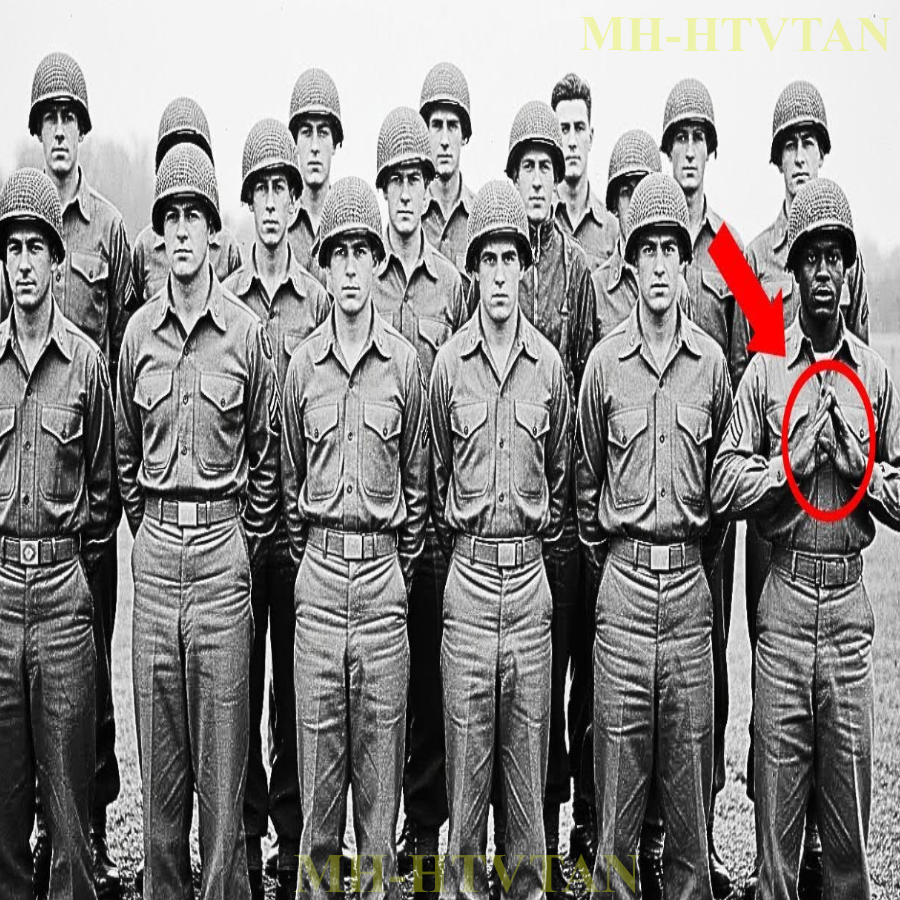

But this one made him stop. The photograph showed 15 soldiers arranged in two neat rows against a backdrop of Virginia pine trees. 14 white soldiers stood in standard military formation, back straight, chins up, arms held rigidly at their sides, their uniforms pressed and identical.

They stared directly at the camera with the serious expressions common to military photography of that era. Young faces marked by the gravity of impending war, but it was the 15th soldier who caught Dr. Patterson’s attention. At the far right edge of the formation stood a black soldier, slightly separated from the others, present but apart, included but excluded.

While his 14 white counterparts maintained perfect military posture, with their hands at their sides, this soldier had positioned his hands deliberately in front of his body. The gesture was subtle but unmistakable once noticed. His hands were forming a specific sign, fingers and palms arranged in a configuration that seemed intentional, purposeful.

Doctor Patterson leaned closer to the photograph, his pulse quickening. He had spent decades studying images of segregated military units, and he had never seen anything quite like this. The soldier’s expression was neutral, professional, giving nothing away. But his hands told a different story.

He requested a highresolution scan of the photograph and spent the next 3 hours examining every detail. The image quality was remarkably good for 1943. Sharp enough to see individual faces clearly to read unit insignas on uniforms to discern the exact positioning of the black soldiers hands. The back of the photograph bore minimal information.

3007th quartermaster company camp Lee VA April 1943 written in faded pencil. Doctor Patterson photographed the image with his phone and sent it to three colleagues. a specialist in African-American cultural history, an expert on World War II military organization, and a scholar who had written extensively about resistance and survival strategies in oppressive systems. His message was brief.

Look at the soldier on the far right. Look at his hands. What do you see? The responses came within hours, each historian noting the same anomaly. The hand gesture was deliberate. The positioning was too precise to be accidental.

The soldier was communicating something, but what? And more importantly, why would he risk such a gesture in an official military photograph during an era when any deviation from expected behavior could result in severe punishment? Dr. Patterson requested permission to remove the photograph from the archives for further study.

That night, alone in his office at the University of Virginia, he laid the image on his desk under a bright lamp and stared at those hands. At that gesture frozen in time for 76 years, waiting for someone to understand its meaning. The soldier’s face offered no clues. young, perhaps 22 or 23, with strong features and eyes that seemed to look beyond the camera into some distant point.

But his hands spoke volumes to anyone who knew how to listen. Dr. Patterson began his investigation with a single question that would consume the next 18 months of his life. What message was this soldier trying to send across the decades? And who was he? Dr. Patterson’s first step was to understand the gesture itself.

He enlarged the photograph until the soldier’s hands filled his computer screen, studying the exact positioning of each finger, the angle of the palms, the spacing between the hands. It wasn’t random. It wasn’t simply a moment caught between movements. It was a deliberate sign held long enough for the photographer to capture it clearly. He began by ruling out what it wasn’t.

It wasn’t standard military hand signals he had memorized those years ago while researching combat communication. It wasn’t American Sign Language in its formal sense. The configuration didn’t match any ASL dictionary he consulted. It wasn’t semaphore or any other official signaling system used during World War II.

But something about the gesture nagged at him. A sense of recognition he couldn’t quite place. He had seen something similar before, though not in military contexts. He began searching through anthropological studies, cultural documentation, historical records of African-American community practices and social customs. Three days into his research, Dr.

Patterson attended a faculty meeting where a colleague, Professor Diane Harper from the African-American studies department mentioned a graduate students thesis on cultural gestures and identity markers within black communities during the early 20th century. After the meeting, Dr. Patterson approached her with the photograph.

Professor Harper studied the image in silence for a long moment, then her eyes widened slightly. “May I show this to someone?” she asked. “I think I know what this is, but I want to confirm it.” She introduced Dr. Patterson to Marcus Williams, a 72-year-old community historian and activist who had spent his life documenting African-American cultural practices and resistance traditions.

Marcus had grown up in Richmond’s historically black neighborhoods and had learned from elders who remembered the Jim Crow era intimately. When Marcus saw the photograph, his reaction was immediate and visceral. He touched the image gently, his finger tracing the outline of the solders’s hands. “He’s making the sign,” Marcus said quietly, his voice thick with emotion. The equality sign. Dr.

Patterson leaned forward. The equality sign? Marcus nodded slowly. It’s not widely known outside our community, especially not among younger folks today. But back then, during segregation, during the worst years of Jim Crow, black folks developed their own ways of communicating, ways of saying things we couldn’t say out loud without risking violence or worse.

He explained that the gesture, hands positioned in a specific configuration that symbolized balance, sameness, equal measure, had been used as a silent affirmation of humanity and dignity. It was a way of saying, I am equal to you, or we deserve equality, without speaking the words that could get you killed in the wrong place at the wrong time.

You’d use it in photographs sometimes, Marcus continued, especially official photographs where you were being documented as inferior or separate. It was a way of leaving evidence, of saying to whoever might see the image in the future, “I was here. I was human. I deserved better than this.” Doctor Patterson felt a chill run down his spine.

“How do you know this? My grandfather taught me,” Marcus said. He served in World War II. He was in a quartermaster company, labor battalion, segregated. He came home and never talked much about the war, but he taught me and my brother certain things. Ways to stand tall when the world wanted you bent, ways to speak truth when speaking could get you hurt.

This sign was one of them. He looked at Dr. Patterson directly. This soldier in your photograph. He knew exactly what he was doing. He was leaving a message. He was testifying. With the meaning of the gesture confirmed, Dr. Patterson faced a new challenge, identifying the soldier who had made it.

The photograph provided limited information, just the unit designation, location, and date. But Dr. Patterson had spent his career navigating incomplete military records, and he knew where to start. He submitted requests to the National Archives in College Park, Maryland, asking for all available records related to the 347th Quartermaster Company stationed at Camp Lee in April 1943.

Quartermaster companies were support units responsible for supplies, equipment, and logistics, essential to military operations, but rarely celebrated or well documented. Companies with black soldiers were even more poorly recorded. Their contributions often reduced to statistics rather than individual names and stories.

The response came three weeks later. two boxes of documents, most badly organized and incomplete. Muster rolls listed names without photographs. Morning reports documented daily activities without personal details. Transfer orders and deployment records showed movements, but revealed little about the men themselves.

Doctor Patterson cross- referenced everything he could find. The 347th Quartermaster Company had been activated in early 1943 and trained at Camp Lee before shipping to England in July of that year. The company consisted of approximately 150 men, nearly all African-American, commanded by white officers. A standard arrangement in the segregated military.

Among the muster roles, Dr. Patterson found names, but no way to connect them to faces in the photograph. He needed more information, more context, more pieces of the puzzle. He began searching for anything related to Camp Lee in 1943.

Local newspapers, base newsletters, command reports, even personal letters donated to various archives. In the Library of Congress, he found a collection of letters written by soldiers from Camp Lee during 1943. Most were from white soldiers describing training expressing homesickness asking for care packages. But buried in the collection was a single letter from a black soldier named Isaiah addressed to his sister in North Carolina.

The letter was dated May 1943, just weeks after the photograph had been taken. Isaiah wrote about the difficult conditions, the discrimination, the exhausting labor details. But one paragraph made Dr. Patterson’s hands tremble as he read, “We had our company photograph taken last month.

I made sure to stand where I could be seen, and I made the sign like daddy taught us. Maybe someday somebody will see it and understand what we went through here. Maybe someday it will matter.” Dr. Patterson immediately requested copies of all documents related to the letter’s donor and any information about the soldier who had written it.

The records indicated the letter had been donated by a woman named Dorothy in 1987, along with several other family documents. A forwarding address was listed in Durham, North Carolina. It took two weeks of searching, but Dr. Patterson finally located Dorothy’s daughter, Patricia, who still lived in Durham. When he called and explained what he had found, Patricia was silent for a long moment.

“My uncle Isaiah served in World War II,” she finally said, her voice shaking. “He died in 1989. My mother kept all his letters, everything he sent home from the war. She always said there was something important in them, something that needed to be remembered.” “Do you have any photographs of your uncle?” Dr. Dr. Patterson asked anything from his time in the service.

I have one, Patricia said. Just one. He’s in uniform standing in front of barracks. It was taken at some camp in Virginia. Dr. Patterson’s heart raced. Would you be willing to share it with me? I think your uncle might be in a photograph I’m researching. A photograph where he left a very important message. 3 days later, an envelope arrived at Dr. Patterson’s office.

Inside was a small faded photograph of a young man in an army uniform, smiling slightly, standing with his hands at his sides. On the back, written in careful script, Isaiah Camp Lee, 1943. Doctor Patterson placed the individual photograph next to the enlarged section of the group formation, showing the soldier making the equality sign. The face was the same. The uniform matched. The timeline aligned perfectly. He had found him.

After 76 years, Isaiah’s message had finally reached someone who understood. With Isaiah identified, Dr. Patterson began piecing together his story from fragments scattered across archives, letters, and family memories. Isaiah had been born in 1921 in a small town outside Durham, North Carolina.

The youngest of four children, his father worked as a carpenter. His mother is a domestic worker for white families. The family attended church every Sunday, maintained a small garden, and saved every penny they could. Isaiah had been an excellent student, graduating from the local black high school in 1939 with honors.

He had dreams of attending college, perhaps becoming a teacher, but the family couldn’t afford tuition. He worked alongside his father for two years, learning carpentry and saving money until December 1941 when everything changed. After Pearl Harbor, Isaiah registered for the draft, like millions of other young American men. He was inducted into the army in February 1942 and sent to Camp Lee for basic training.

Like nearly all black soldiers, he was assigned to a service unit rather than a combat role, the 347th quartermaster company, where he would spend the war loading trucks, organizing supplies, and performing the essential but unglamorous labor that kept the military functioning. Patricia shared more of her uncle’s letters with Dr.

Patterson, and together they painted a picture of a thoughtful, observant man struggling with the contradictions of serving a country that denied him basic rights. In one letter from March 1943, Isaiah wrote, “We work twice as hard as the white companies and get half the respect. The officers treat us like we’re stupid, like we can’t be trusted with anything important.

But we do our jobs and we do them well because that’s who we are. We have dignity even when they try to take it from us.” Another letter from April 1943, the same month as the photograph, revealed Isaiah’s awareness of being documented and his determination to leave evidence. They took our company picture today.

All of us lined up nice and neat, like we’re really part of this army as equals. But I made sure anyone looking close enough will see the truth. I made the sign Daddy taught me, the one that says what we can’t say out loud. Someday somebody’s going to look at that picture and understand.

Doctor Patterson also discovered that Isaiah’s father had been active in early civil rights organizing in North Carolina, working quietly to register black voters and advocate for better schools and fair treatment. He had taught his children about dignity, resistance, and the importance of leaving evidence, of making sure their truth was documented even when it couldn’t be spoken. The equality sign that Isaiah made in the photograph wasn’t just a personal gesture.

It was part of a family tradition of quiet resistance, of finding ways to assert humanity and demand recognition, even in systems designed to deny both. Isaiah had shipped to England in July 1943 with his company, then crossed to France after D-Day in 1944.

His unit supported combat operations, hauling ammunition and supplies through dangerous territory, often under fire, but never officially recognized as combat soldiers. He survived the war and returned to North Carolina in 1946. According to Patricia, Isaiah came home changed. He rarely spoke about his service, but he became involved in local civil rights efforts, attending meetings, supporting voter registration drives, and quietly advocating for equality.

He worked as a carpenter like his father, married in 1950, raised three children, and lived a long life. He died in 1989 at the age of 68, surrounded by family. He used to tell us that being seen was important, Patricia said during a phone conversation with Dr. Patterson. He’d say, “They try to make us invisible, but we’re here. We exist, and someday people will know we were here and what we contributed.

” I never fully understood what he meant until now. Dr. Patterson asked if any other family members might remember Isaiah or have information about his service. Patricia mentioned that Isaiah’s eldest daughter, his niece Claudia, lived in Atlanta and had spent considerable time with her father before his death, recording some of his stories. Within days, Dr.

Patterson was on a plane to Atlanta carrying the photograph and copies of Isaiah’s letters, ready to learn more about the man who had made a silent declaration of equality in 1943 and trusted that someday someone would understand. Claudia opened her door in Atlanta and immediately recognized the soldier in the photograph. “That’s my father,” she said, her voice catching.

I’ve never seen this picture before, but that’s definitely him. She invited Dr. Patterson inside, and for the next four hours, they sat at her dining room table, surrounded by photographs, letters, and recordings as she shared everything she knew about Isaiah’s life and legacy.

Claudia was 62 years old, a retired social worker who had dedicated her career to serving marginalized communities. She explained that her father had rarely discussed the war when she was young, but in his final years, sensing his time was limited, he had begun opening up. She had recorded several of their conversations, preserving his voice in his stories. “He told me about the photograph,” Claudia said, pulling out a small digital recorder.

Not specifically, but he talked about making sure he left evidence. He said that in a system where speaking up could get you punished or killed, you had to find other ways to testify. She played one of the recordings. Isaiah’s voice, aged but strong, filled the room. When you’re treated as invisible, when they act like you don’t matter or don’t exist, you have to remind yourself and remind the world that you do.

Every chance I got in whatever small way I could, I made sure there was proof that I was there, that I saw what was happening, that I deserve better. That photograph they took of our company, I made the sign my father taught me. I figured maybe someday somebody would see it and understand what we went through. Dr. Patterson listened with tears in his eyes. Here was confirmation directly from Isaiah himself.

Not speculation or interpretation, but his own words explaining exactly what he had done and why. Claudia shared more recordings. Isaiah talked about the daily humiliations of serving in a segregated military, being denied access to facilities that German prisoners of war could use, being called slurs by the officers who commanded him, being assigned the most dangerous and degrading tasks, while being told he wasn’t brave enough for combat.

He described the exhaustion of working twice as hard to prove his worth, only to be dismissed and degraded regardless of his performance. But he also talked about moments of resistance and solidarity. He described how black soldiers in his unit supported each other, shared information, found small ways to assert their dignity.

He mentioned the equality sign specifically, explaining that several men in his company knew the gesture and used it when they could in photographs in moments when they were being observed or documented as a way of saying silently what they couldn’t say aloud. We weren’t just victims, Isaiah’s recorded voice said firmly. We were witnesses. We saw the injustice.

We experienced it and we documented it however we could. We knew that history tries to erase uncomfortable truths, so we made sure to leave evidence that couldn’t be erased. Claudia also shared her father’s post-war activism. After returning to North Carolina, Isaiah had worked with the NAACP, participated in early civil rights organizing, and mentored young people in the community.

He had taught them the same lessons his father had taught him about dignity, resistance, and the importance of being seen and counted. He used to say that the equality sign was more than just a gesture. Claudia explained it was a philosophy. It meant refusing to accept inferior treatment, insisting on your humanity, and leaving proof for future generations that you existed and that you mattered. Dr.

Patterson asked if he could make copies of the recordings and if Claudia would be willing to participate in sharing Isaiah’s story publicly. She agreed immediately. My father would want this known,” she said. “He spent his whole life making sure black contributions and black experiences weren’t erased from history. This photograph, this story, it’s exactly what he fought for.

People need to know what soldiers like him endured, and they need to know that even in the worst circumstances, we found ways to resist and to testify.” Before Dr. Patterson left Atlanta, Claudia gave him one more item, a small notebook that Isaiah had kept during the war. Most of the entries were mundane notes about supplies, schedules, reminders.

But on one page dated April 1943, Isaiah had written, “Comp today, made the sign for daddy for my children, for whoever sees this someday and understands.” Dr. Patterson held the notebook carefully, realizing he was holding direct evidence of one man’s quiet act of resistance, an act that had waited 76 years to be fully understood and honored. With Isaiah identified and his story documented, Dr.

Patterson turned his attention to the other 14 soldiers in the photograph. Who were they? What had they experienced? And most importantly, had any of them known what Isaiah was doing when he made that gesture? He returned to the military records with renewed focus. This time working to identify every soldier in the formation.

Using the unit rosters, deployment records, and what little documentation existed, he slowly began putting names to faces. The process was painstaking, comparing facial features to other photographs when available, cross-referencing service numbers and deployment dates, tracking down any surviving records or family histories.

Most of the white soldiers had been from Virginia, Maryland, and other Mid-Atlantic states. They had trained at Camp Lee, deployed to England, and participated in the logistics operations, supporting the D-Day invasion and subsequent campaigns across Europe. Several had been killed in action or died from disease. Others had returned home, started families, pursued careers, and lived normal post-war lives. Dr.

Patterson found obituaries, newspaper clippings, memorial notices. He discovered that one soldier, Robert, had become a teacher after the war. Another, William, had worked in manufacturing. A third, James, had died in France in 1944 when his supply convoy was attacked. Each name represented a life, a story, a unique experience of the war. But Dr.

Patterson was particularly interested in whether any of these soldiers had been aware of Isaiah’s presence, or his gesture. Had they noticed, had they understood? or had Isaiah’s silent testimony gone completely unrecognized by the men standing just feet away from him? He found a partial answer in an unexpected place.

The son of one of the white soldiers, a man named Thomas, who had been standing in the front row of the formation, contacted Dr. Patterson after reading a preliminary article about the research. The son, Richard, now in his 70s, said his father had mentioned the photograph occasionally before his death in 1995.

“My father kept a copy of that photo his whole life,” Richard said during a phone conversation. It was in his study in a frame on his desk. When I asked him about it once, he said something strange. He said, “That picture reminds me that I didn’t see what I should have seen.” I never understood what he meant. Dr. Patterson asked if Richard would be willing to share any of his father’s papers or letters from the war.

Richard agreed and mailed several boxes of materials. Among them was a letter Thomas had written to his wife in 1968, 25 years after the photograph was taken and during the height of the civil rights movement. In the letter, Thomas reflected on his military service and his relationship with black soldiers.

I’ve been thinking a lot about the war lately, watching what’s happening in this country now. We had black soldiers in support roles, men who worked harder than most of us ever did, and we barely acknowledged their existence. They were there doing essential work, and we treated them like they were invisible.

I look at that old company photo sometimes, and I see that young black soldier at the edge, and I wonder what he thought about us, about the army, about serving a country that treated him that way. I wish I had seen him then the way I see him now, as a fellow soldier who deserved respect and equality. I was blind to so much back then. The letter moved Dr. Patterson deeply.

It suggested that at least one of the white soldiers had eventually recognized the injustice, even if it had taken decades. But it also confirmed that during the actual moment of the photograph, Isaiah had been functionally invisible to most of his white counterparts, present in the frame, but unseen as a full human being. Dr. Patterson continued identifying the other soldiers and reaching out to their families when possible.

Most had no idea their fathers or grandfathers had been photographed alongside a black soldier, and several expressed surprise that black soldiers had even been at Camp Lee during that period. The selective memory and incomplete historical narratives, had rendered Isaiah invisible, even in retrospect.

But a few family members, particularly younger generations, were moved by the story and eager to learn more. They began asking questions about segregation in the military, about the experiences of black soldiers, about the systemic injustices that had been normalized during that era. The photograph was becoming more than just historical documentation.

It was prompting conversations, challenging assumptions, and forcing people to confront uncomfortable truths about the past and its continuing legacy. Dr. Patterson spent eight months compiling his research into a comprehensive report. He documented Isaiah’s identity and life story, analyzed the meaning and significance of the equality gesture, contextualized the photograph within the broader history of segregation in the military, and traced the experiences of the other soldiers in the formation.

The result was a 150page document that combined rigorous historical scholarship with deeply human storytelling. He presented his findings first at an academic conference on World War II history in Washington, DC. The presentation room was packed with historians, military scholars, and journalists. Dr.

Patterson displayed the photograph on a large screen, walking the audience through his investigation step by step. The discovery, the identification of the gesture, the search for Isaiah, the recordings, the letters, the broader context. When he finished, the room sat in silence for several long seconds before erupting in applause.

During the question and answer session, multiple scholars commented that they had never seen such clear evidence of deliberate documented resistance within the segregated military. Several mentioned that they would be returning to their own archives to look for similar gestures and hidden messages and photographs they had previously examined only superficially.

But the real impact came when the story moved beyond academic circles. A journalist from the Washington Post attended the conference and wrote a feature article titled The Solders’s Silent Message: How One Man’s Gesture in a 1943 photo speaks across generations.

The article included the photograph, excerpts from Isaiah’s letters and recordings, and interviews with Claudia and Dr. Patterson. The story went viral within hours. Major news outlets picked it up. CNN, NPR, the New York Times, BBC, social media exploded with shares and commentary. The photograph appeared everywhere, often with close-ups highlighting Isaiah’s hands in the equality gesture.

The response from the African-American community was particularly powerful. People shared their own family stories of resistance and survival during Jim Crow. Elders mentioned that they recognized the gesture that they had been taught similar signs by grandparents and great-grandparents.

Younger generations expressed amazement that such a system of silent communication had existed and gratitude that these stories were finally being told. Civil rights organizations reached out to Dr. Patterson asking to use the photograph in educational materials and exhibitions. The National Museum of African-American History and Culture in Washington DC.

They contacted him about acquiring the original photograph and creating a permanent display about Isaiah and the broader phenomenon of cultural resistance in the segregated military. Schools incorporated the story into their curricula. Teachers used it to discuss World War II, segregation, resistance, and the importance of questioning official narratives and looking closely at historical evidence.

Students wrote essays, created art projects, and conducted their own research into local histories of discrimination and resistance. Dr. Patterson also received messages from active duty military personnel, particularly black service members, who said the story resonated deeply with their own experiences of navigating predominantly white institutions and finding ways to assert their identity and demand respect.

But perhaps the most moving responses came from ordinary people, descendants of black soldiers, family historians, community members who said the photograph and Isaiah’s story validated experiences and stories they had been told, but that had never been officially recognized or documented. One woman wrote, “My grandfather served in World War II and came home angry and silent.

He died when I was young, and I never understood why he seemed so bitter about his service.” Seeing this photograph and learning Isaiah’s story helps me understand what my grandfather might have gone through and why it affected him so deeply. Thank you for making his experience visible.

The photograph that had sat in an archive for decades, noticed by no one, had become one of the most significant historical images of World War II, not because it showed dramatic combat or historic meetings, but because it captured one man’s quiet, courageous refusal to be invisible. 6 months after the story broke nationally, the National Museum of African-American History and Culture opened a special exhibition titled Silent Testimony: Resistance and Dignity in the Segregated Military.

The centerpiece was Isaiah’s photograph displayed at large scale with detailed annotations explaining the context, the gesture, and the significance. But the exhibition went far beyond just that single image. Dr. Patterson had continued his research and with the help of other historians and community members had identified 12 additional photographs from World War II showing black soldiers making similar gestures, equality signs, dignity symbols, cultural markers that had gone unnoticed for decades, but that represented a widespread practice of silent resistance

and documentation. Each photograph was displayed with accompanying materials, letters from the soldiers if available, historical context about their units in service, information about the gestures they were making, and updates about their post-war lives.

The exhibition revealed a hidden network of resistance, black soldiers across different units, different locations, different years of the war, all finding ways to leave evidence of their humanity and their demands for equality. The exhibition also included a section on the broader history of cultural gestures and coded communication within black communities during Jim Crow.

Historians and cultural experts contributed essays and artifacts showing how African-Americans had developed sophisticated systems of non-verbal communication to navigate dangerous situations, share information, and maintain dignity in oppressive circumstances. Interactive elements allowed visitors to learn some of these gestures and understand their meanings and origins.

Video interviews with elders who remembered the era provided first-person testimony. Recordings like those Claudia had shared of her father, Isaiah, played on loop, letting visitors hear directly from the soldiers themselves. The opening ceremony drew more than a thousand people.

Claudia attended along with Patricia and several other descendants of soldiers featured in the exhibition. Veterans organizations sent representatives. Active duty military personnel came in uniform to pay respects. Civil rights leaders spoke about the continuing relevance of the stories being told. When Claudia stood before the massive display of her father’s photograph, seeing his young face and his deliberate gesture honored and explained, she wept. He would be so proud, she said to Dr. Patterson, who stood beside her.

He spent his whole life trying to make sure black contributions weren’t erased. Now his own story is being told in the National Museum. He’s finally being seen. The exhibition was scheduled to run for 6 months, but proved so popular that it was extended indefinitely and eventually became part of the museum’s permanent collection. School groups visited by the hundreds.

Veterans came to pay respects and share their own stories. Families brought children and grandchildren to teach them about this hidden chapter of history. Media coverage continued for months. Documentary filmmakers began working on a featurelength film about Isaiah and the other soldiers.

Academic publishers released books exploring the broader phenomenon of visual resistance and oppressive systems. University courses incorporated the exhibition materials into their syllabi. But perhaps the most significant impact was how the exhibition changed the way people looked at historical photographs. Museums, archives, and historical societies across the country began re-examining their collections with new eyes, looking for similar gestures and hidden messages they might have previously missed. Dozens of new discoveries emerged.

Photographs showing resistance, documentation, silent testimony that had been invisible to researchers who hadn’t known what to look for. The exhibition sparked a methodology shift in historical research, an acknowledgement that marginalized people often left evidence of their experiences in subtle coded ways that required cultural knowledge and careful attention to detect.

It validated the importance of community knowledge and oral history in interpreting visual evidence. And it demonstrated that official narratives often missed or deliberately excluded crucial elements of the past that could only be recovered by listening to and learning from the communities who had lived through them. Isaiah’s gesture in that 1943 photograph had accomplished exactly what he had hoped.

It had testified. It had documented. And ultimately, it had been seen and understood. Three years after Dr. Patterson’s initial discovery, the photograph, and Isaiah’s story had fundamentally changed multiple fields of study and public understanding of World War II history, the impact rippled outward in ways no one had anticipated, touching education, military policy, cultural preservation, and collective memory.

Universities established new research initiatives focused on recovering hidden narratives from visual evidence. Graduate students wrote dissertations analyzing photographs with attention to details previously ignored. Hand positions, body language, spatial arrangements that might encode resistance or testimony.

Conferences dedicated entire panels to methodologies for detecting and interpreting silent communication in historical images. The military itself took notice. The Department of Defense commissioned a comprehensive review of how African-American service members had been treated throughout American military history with particular focus on World War II.

The review acknowledged systematic discrimination, validated the experiences of black soldiers like Isaiah, and committed to ensuring these stories were included in official military histories and taught at servicemies. Several military bases established memorials or dedicated spaces honoring black soldiers who served in segregated units.

Camp Lee, where Isaiah’s photograph had been taken, created a permanent installation featuring the image alongside historical context and information about the 347th Quartermaster Company. Veterans and their families could visit and pay respects to those who had served despite facing discrimination from the very institution they were defending. Educational materials proliferated.

Textbook publishers revised their World War II chapters to include information about segregation in the military and the resistance strategies employed by black soldiers. Documentary films about Isaiah and similar stories aired on major networks and streaming platforms. Museums across the country requested reproductions of the photograph for their own exhibitions.

The gesture itself, the equality sign that Isaiah had made, became a symbol adopted by activists and educators. It appeared in protests, in artwork, in educational materials advocating for racial justice. Some military units with predominantly black personnel incorporated it into informal traditions, honoring the legacy of soldiers like Isaiah, who had demanded dignity and equality.

Claudia became a sought-after speaker, sharing her father’s story at schools, community centers, and conferences. She emphasized that Isaiah’s act wasn’t unique, that countless black Americans had found creative ways to resist oppression and document their experiences, and that many of those stories remained untold and waiting to be discovered.

My father’s photograph got noticed because a dedicated historian took the time to look closely and ask questions she would tell audiences. But there are thousands more photographs, letters, artifacts sitting in atticss and archives with similar stories locked inside them. We need to keep looking, keep asking, keep listening, especially to the communities whose voices have been excluded from official histories. Dr.

Patterson published a book titled Silent Testimony: Visual Resistance in the Segregated Military, 1941 to 1945, which became required reading in college history courses nationwide. He used the advance and royalties to establish a scholarship fund for students studying African-American military history, ensuring that future scholars would continue the work of recovering and honoring these hidden narratives.

The photograph also sparked important conversations about representation and memory. Families began re-examining their own collections, looking for ancestors who might have left similar messages. Community archives worked to digitize and preserve photographs and documents before they were lost. Genealogologists collaborated with historians to connect visual evidence with family stories and oral histories.

But perhaps the most profound legacy was how the photograph changed individual lives. Young black students saw Isaiah’s image and recognized themselves. saw that resistance and dignity had deep historical roots, that their ancestors had fought battles for recognition and equality in every generation, that courage could take many forms, including silent gestures that spoke across decades.

Veterans from more recent conflicts, Iraq, Afghanistan, reached out to share how Isaiah’s story resonated with their own experiences of serving while facing discrimination or questioning their treatment. The photograph became a touchstone for conversations about how far the military had come in terms of integration and equality and how far it still needed to go.

Isaiah’s descendants, his children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren, found themselves connected to a larger community of people who valued and honored his legacy. Claudia’s grandchildren grew up knowing their great-grandfather’s story, understanding that he had been part of something significant, that his quiet act of resistance mattered and would be remembered. The photograph hung in countless classrooms, offices, homes.

People looked at it and saw not just 15 soldiers in a formation, but a testament to the power of bearing witness, the importance of leaving evidence, and the courage it takes to insist on your humanity when systems try to deny it. 5 years after the photograph’s discovery, Dr. Patterson returned to the Virginia Historical Society, where his investigation had begun.

He was there to give a lecture, but he arrived early and asked to see the archives, where the image had been stored for decades before he noticed it. The archivist led him to the climate controlled room, to the very box where the photograph had waited in obscurity. Dr.

Patterson stood there for a long moment thinking about all the researchers who had probably looked at that image over the years and seen nothing remarkable. Just another standard military portrait from World War II. How many other photographs are in these archives with messages we haven’t decoded yet? He wondered aloud. The archivist smiled. Since your discovery, we’ve had dozens of researchers going through our collection, specifically looking for similar gestures and hidden communications.

We found three more so far. Different wars, different contexts, but the same principle. People leaving evidence, trusting that eventually someone would understand. That evening, Dr. Patterson’s lecture hall was packed. He displayed Isaiah’s photograph on the screen and told the full story.

The discovery, the investigation, the identification, the meanings, the impact. But he concluded with something new. A photograph that had been discovered just weeks earlier in a private collection in South Carolina. The image showed a group of black women who had worked as nurses during World War II. Photographed at a military hospital in 1944. And there, partially hidden by the way several women had positioned their hands in their laps, was a variation of the equality sign.

A gesture so subtle it would be invisible to anyone not specifically looking for it, but unmistakable once noticed. Isaiah’s photograph was not an isolated incident, Dr. Dr. Patterson said to the hushed audience, “It was part of a broader phenomenon, a practice of silent testimony, of leaving coded evidence, of refusing to let history erase the truth of discrimination and the dignity of resistance.

We’re only beginning to understand how widespread this practice was, and how many messages are still waiting to be decoded.” He clicked to another slide, showing a dozen recently discovered photographs, each containing similar gestures or hidden messages. Now, these images have been sitting in archives, atticts, and albums for decades.

Some have been digitized and posted online where millions could see them. But no one noticed what was there because we weren’t looking with the right eyes. We weren’t asking the right questions. We weren’t bringing the necessary cultural knowledge to the interpretation. He paused, letting that sink in. History is not just what’s written in official documents and taught in textbooks.

History is also what’s hidden in plain sight, waiting for someone with the knowledge, the curiosity, and the commitment to look closely enough to see it. Isaiah and others like him trusted that their messages would eventually reach us. They believed that future generations would care enough to look, to ask, to understand. Dr.

Patterson concluded his lecture by showing Isaiah’s photograph one more time. That young soldier at the edge of the formation, his hands making a simple gesture that had spoken across 76 years before being heard. Every time we recover one of these hidden messages, every time we identify a soldier like Isaiah and tell his story, we honor not just that individual, but the broader principle he represented.

The truth matters. The documentation matters. that bearing witness matters even when especially when the systems in power want certain truths to remain invisible. The audience rose in a standing ovation. Afterward, several people approached Dr.

Patterson with photographs from their own family collections, asking if he would examine them for similar gestures or hidden messages. He agreed to every request, knowing that each image might contain another story waiting to be told, another message waiting to be decoded, another instance of resistance and dignity that deserved recognition. Later that night, alone in his hotel room, Dr.

Patterson looked one more time at the photograph that had started everything. He thought about Isaiah, that young man who had served his country while being treated as less than fully human, who had found a way to leave evidence of his experience in his demand for equality, who had trusted that someday someone would see and understand.

Isaiah had been right to trust. His message had been received. His story had been told. His gesture had reached across generations and changed how thousands of people understood history, resistance, and the power of bearing witness. But more than that, Isaiah’s act had sparked a movement, a commitment among historians, archavists, educators, and ordinary people to keep looking, to keep questioning, to keep listening to the voices that official narratives had excluded or suppressed.

The photograph would outlive everyone connected to it. Long after Dr. Patterson, Claudia, and all the descendants were gone. That image would remain a young soldier in 1943 making a simple gesture with his hands, declaring his equality, documenting his truth, speaking to a future he would never see, but believed in nonetheless.

And that belief, that trust in future generations to eventually see, understand, and honor the truth, was perhaps the most powerful message of all. Isaiah’s hands would continue speaking. His testimony would continue resonating. His quiet act of courage would continue inspiring because he had been seen. He had been heard.