THE BEAUTIFUL NAZI REVENGE OF AN 18-YEAR-OLD BEAUTY: Dita Kraus – The Girl Who Twice Escaped Auschwitz Concentration Camp, Whose Enemies Had to Surrender to Her Resilience _us

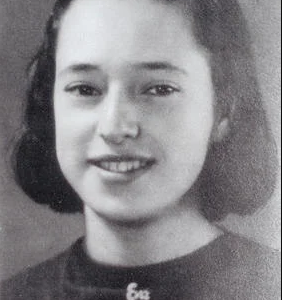

Dita Kraus, born Edith Polachová on July 12, 1929, in Prague, Czechoslovakia, endured the unimaginable horrors of the Holocaust as a young Jewish girl. Deported to the Theresienstadt Ghetto and later to Auschwitz and Bergen-Belsen, she faced starvation, brutality, and loss, yet emerged as a symbol of resilience. As the “librarian” of the Children’s Block in Auschwitz’s Theresienstadt family camp, she preserved a flicker of hope for children. Her survival and subtle acts of defiance, culminating in a life rebuilt after the war, reflect an enduring spirit. This analysis, for history enthusiasts, explores Dita’s journey, her role in the camps, and her quiet revenge through survival and legacy.

Dita grew up as the only child of Elisabeth and an unnamed father in Prague, a city rich with Jewish culture. Her grandfather, Johann Polach, a Social Democratic senator in the Czechoslovak National Parliament, instilled a sense of civic duty. Her parents nicknamed her “Dita,” a name that became synonymous with her courage. When Adolf Hitler was appointed German Chancellor on January 30, 1933, Dita was just three years old, unaware of the gathering storm.

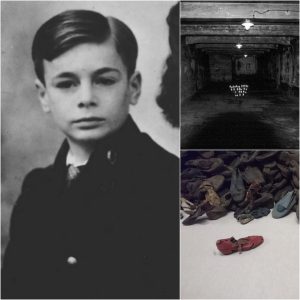

By late summer 1938, Hitler’s annexation of the Sudetenland, a key defensive region of Czechoslovakia, signaled growing danger. The Polach family considered emigration, but restrictive global policies limited options for Jewish refugees. On March 15, 1939, Nazi Germany occupied the remaining Czech territories, establishing the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia. Anti-Jewish laws swiftly followed, stripping Jews of rights and livelihoods. Amid this oppression, the Hagibor youth center in Prague, led by Fredy Hirsch, a German-Jewish athlete and Zionist, offered Dita and other children a haven for play and learning.

Theresienstadt: A Glimpse of Hope Amid Despair

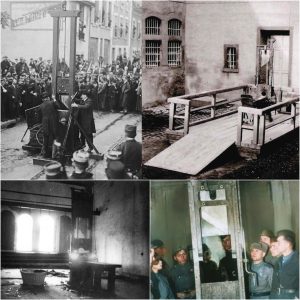

In November 1941, Reinhard Heydrich established the Theresienstadt Ghetto in Terezín, a fortress town used as a propaganda “model ghetto.” Dita and her parents were deported there in November 1942. The overcrowded ghetto lacked water, electricity, and privacy, with men and women housed in separate barracks. Dita slept on the floor inside the ramparts, battling bedbugs, fleas, and hunger. Prisoners aged 14 to 65 were forced to work, while the elderly received 60% less food than laborers. Fredy Hirsch, as Head of the Children and Youth Department, organized activities to maintain morale, creating a semblance of normalcy for children like Dita.

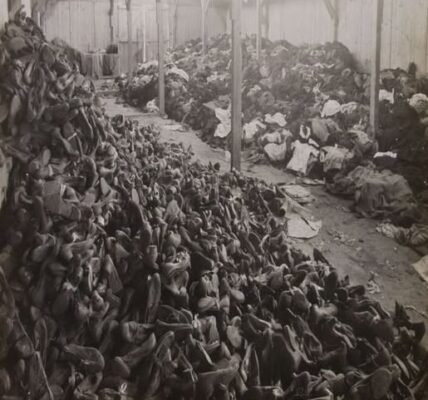

Life in Theresienstadt was harsh, but Dita found purpose in Hirsch’s programs, which fostered education and community. However, the ghetto served as a waystation to death camps. On October 26, 1942, the first transport from Theresienstadt to Auschwitz carried 1,866 people; only 247 were registered as prisoners, while 1,619 were gassed upon arrival.

Auschwitz: The Children’s Block and Defiance

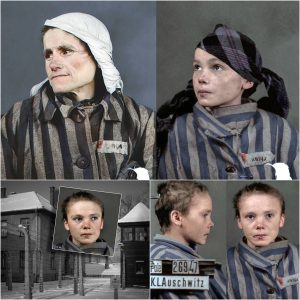

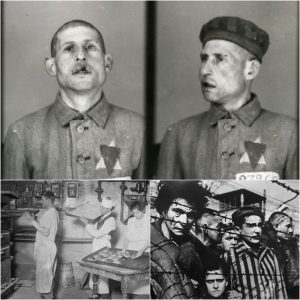

In December 1943, Dita and her parents were deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau’s Theresienstadt family camp (BIIb), established on September 8, 1943, for propaganda purposes. Housing around 18,000 Jews from Terezín between 1943 and 1944, it allowed families to stay together, unlike other camps, but conditions remained brutal—hunger, beatings, and minimal water. The camp’s 32 wooden barracks, former horse stables, held 300 prisoners each, with narrow apertures for ventilation. Meals consisted of a midday bowl of soup and evening bread with margarine or watery jam.

Dita, then 14, became the “librarian” of the Children’s Block (Barrack 31), led by Fredy Hirsch. Hirsch persuaded camp authorities to allow the block, arguing it kept children occupied while parents labored. He secured extra food, indoor roll calls, and heating, and enforced strict hygiene to combat lice. Dita managed a small collection of smuggled books, offering children a refuge through stories and learning. This role, though small, was a quiet act of resistance, preserving humanity amid dehumanization.

In February 1944, the Auschwitz resistance decoded “SB6,” meaning “special treatment” or gassing after six months. On March 8, 1944, 3,800 prisoners from the September transport, including Hirsch, were murdered in the gas chambers. Dita, arriving in December, knew her time was limited. In May 1944, Josef Mengele, the notorious “Angel of Death,” conducted selections for labor. Dita was chosen for work, sparing her from immediate death. The family camp was liquidated in July 1944, with 7,000 gassed; Dita and 3,000 others were sent to labor camps like Stutthof and Neuengamme subcamps.

Bergen-Belsen and Liberation

By March 1945, as the war neared its end, the Neuengamme subcamps were evacuated due to catastrophic death rates. Dita and her mother were transferred to Bergen-Belsen, where conditions were dire—overcrowding, disease, and starvation. On April 15, 1945, the British 11th Armored Division liberated the camp, providing food and clothing. Dita and Elisabeth survived, but Elisabeth died shortly after due to the toll of captivity. Dita’s father had perished earlier, likely in Auschwitz.

Dita’s revenge was not violent but profound: she survived, reclaiming her life against the Nazis’ intent to destroy it. Returning to Prague, she met Otto Kraus, a fellow survivor. They married in 1947, moved to Israel in 1949, and raised three children, finding happiness despite their scars. Otto passed away in 2000, but Dita continued sharing her story, notably through her memoir A Delayed Life.

Legacy of Resilience

Dita’s role as the “librarian” and her survival embody resistance through endurance and hope. The Children’s Block, under Hirsch’s leadership, defied Nazi brutality by nurturing young minds. Her story, preserved through her writings and testimonies, challenges the narrative of passive victimhood, highlighting the power of small acts in genocide.

Historians see Dita as a symbol of youth resilience, her guardianship of books a metaphor for safeguarding culture. Her post-war life—building a family and sharing her story—serves as a quiet triumph over Nazi ideology.

Dita Kraus’s journey from a Prague childhood to surviving Auschwitz and Bergen-Belsen reflects extraordinary courage. Her role in the Children’s Block and survival were acts of defiance, her life after the war a testament to reclaiming humanity. For history enthusiasts, Dita’s story urges remembrance of Holocaust victims and celebration of their resilience. Her legacy inspires us to preserve hope and culture, ensuring such atrocities are confronted and never repeated.