THE GALLOWS’ DUE: Martin Gottfried Weiss – A Career of Carnage Spanning Dachau and Majdanek, From the Spring of 8,000 Deaths to the Unchecked Killings That Sealed His Fate _us202

CONTENT WARNING: This article details graphic acts of violence, human experimentation, and genocide during the Holocaust. It is intended for historical education and remembrance, not to glorify or sensationalize cruelty. Reader discretion is advised.

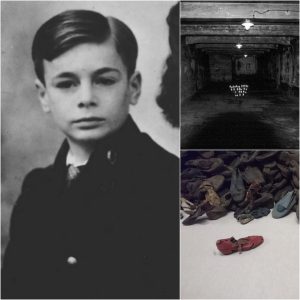

He was not the most famous name among the SS monsters, but Martin Gottfried Weiss left behind a trail of corpses that stretched from the pine forests of Lublin to the barbed wire of Bavaria. Born on 3 June 1905 in Weiden in der Oberpfalz, the son of a modest court clerk, nothing in his early life suggested the cold-blooded efficiency he would later display in running two of the Reich’s most lethal concentration camps.

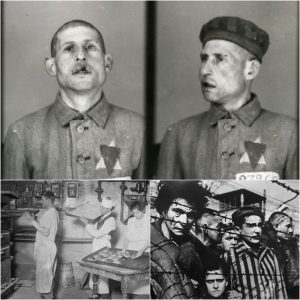

Weiss joined the NSDAP in 1932 and the SS a year later. By 1938 he was already adjutant at Dachau, learning the machinery of terror under some of its earliest commandants. In April 1942, the SS sent him east, to the newly constructed extermination camp at Majdanek, near Lublin. There, under Odilo Globocnik’s Operation Reinhard, Weiss served as Schutzhaftlagerführer – the man directly responsible for the camp’s internal “order.”

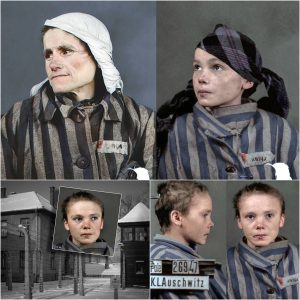

It was in the spring and summer of 1942 that Majdanek earned its most horrifying footnote. Between March and June alone, approximately 8,000 prisoners – mostly Polish Jews, Soviet POWs, and political detainees – were murdered under Weiss’s administration. Gassing with Zyklon B had not yet begun on a large scale; most were shot in the woods behind the camp or died from deliberate starvation and typhus epidemics that the SS refused to control. Witnesses later recalled Weiss personally touring the blocks, deciding which barracks would receive no food at all, calmly marking the lists with a pencil while men, women and children collapsed around him.

In September 1943, after a brief stint as commandant of the Neuengamme sub-camp Arbeitsdorf, the SS returned him to Dachau – this time as commandant of the main camp itself, replacing the dismissed Eduard Weiter. He arrived in April 1944 and would remain until the camp’s liberation exactly one year later.

Under Weiss, Dachau became a factory of slow death. More than 30,000 prisoners were crammed into barracks built for 8,000. Medical experiments – high-altitude, freezing, malaria, and seawater – continued unabated. Invalid transports arrived almost weekly from Auschwitz as it was evacuated; most were simply shot in the crematorium yard or left to die in the overflowing “invalid blocks.” When typhus broke out in the winter of 1944–45, Weiss forbade any improvement in sanitary conditions and ordered the execution of anyone too weak to stand for roll call. The deathchaft records show at least 4,000 registered deaths in the first four months of 1945 alone – a conservative figure that excludes the thousands murdered without registration.

American troops liberated Dachau on 29 April 1945. Weiss had fled southward two days earlier with a small entourage, hoping to blend into the chaos of the collapsing Reich. He was captured near Munich on 2 May by a U.S. Army patrol. He still wore his SS-Standartenführer uniform and carried forged papers identifying him as “Hans Schmitt.”

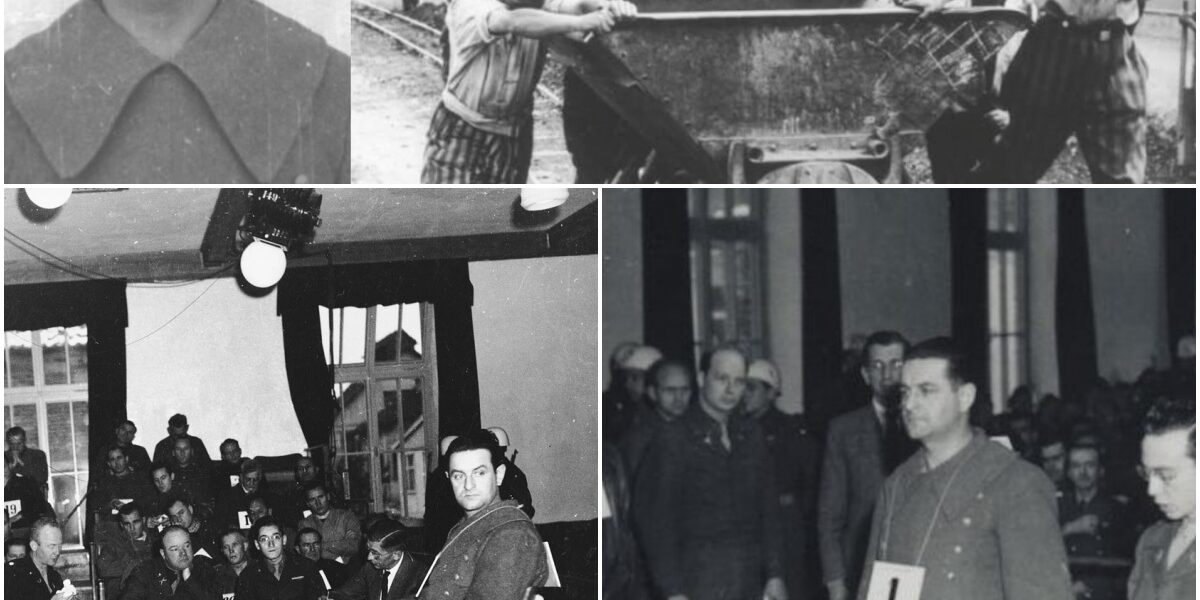

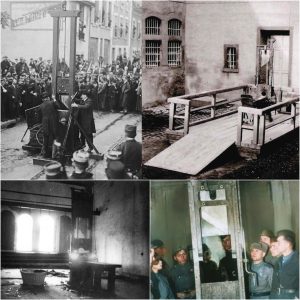

The Dachau Trials began in November 1945 on the very grounds of the former camp. The main trial – United States v. Martin Gottfried Weiss et al. – opened on 15 November. Forty men and one woman stood accused of war crimes committed at Dachau and its 123 subcamps. Weiss, case defendant No. 1, faced charges of “acting jointly and in pursuance of a common design to subject prisoners to killings, beatings, tortures, starvation, abuses and indignities.”

The evidence was overwhelming. Former prisoners – Polish priests, French resistance fighters, Norwegian students, Russian officers – took the stand one after another. They described Weiss walking the camp with his dog Lord, a massive wolfhound trained to attack on command. They spoke of the “Weiss whip,” a special riding crop he used himself. They told of Christmas 1944, when he ordered the hanging of twelve escaped Soviet officers recaptured nearby, forcing the entire camp to watch while a band played cheerful marches.

On 13 December 1945, after only nine days of deliberation, the military court pronounced its verdict: death by hanging for Martin Gottfried Weiss and thirty-five of his co-defendants.

Weiss showed no emotion. He spent his last months in the same war crimes enclosure where he had once imprisoned thousands. On the night of 28 May 1946, he wrote a brief letter to his wife claiming he had only “done his duty.” At dawn on 29 May 1946, Master Sergeant John C. Woods – the U.S. Army’s veteran executioner – led him to the gallows erected in the former SS workshop area at Landsberg Prison.

Weiss was the eighth man hanged that morning. The trapdoor opened at 10:03 a.m. His body dropped, the rope snapped taut, and the former commandant of Dachau and Majdanek was pronounced dead fourteen minutes later.

The American newsreel cameras rolled. The footage shows a small, ordinary-looking man in a patched Wehrmacht coat, hands bound behind his back, stepping forward without hesitation. There is no final statement, no plea for mercy, no theatrical defiance – only the same bureaucratic calm he had displayed while signing thousands of death orders.

Martin Gottfried Weiss was forty years old when the rope ended a career that had claimed, by the most conservative estimates, well over 40,000 lives. The gallows had finally collected their due.