THE LAST MAN DECAPITATED IN THE WEST: The Shocking Death of Hamida Djandoubi Under the Blade That Ended 200 Years of Guillotine History in Europe – THE END OF AN ERA

EXTREMELY SENSITIVE CONTENT – 18+ ONLY:

This article discusses sensitive historical events related to capital punishment and violent crimes, including acts of judicial violence and descriptions of torture and murder. The content is presented for educational purposes only, to foster understanding of the past and encourage reflection on how societies can prevent similar injustices in the future. It does not endorse or glorify any form of violence, crime, or extremism.

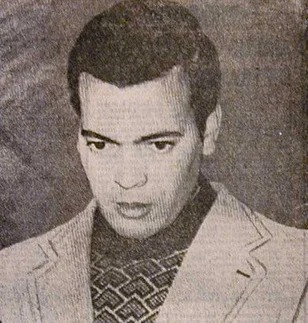

In the waning years of capital punishment in France, Hamida Djandoubi, a Tunisian immigrant, became a pivotal figure in legal history as the last person executed by guillotine on September 10, 1977. Convicted of the kidnapping, torture, and murder of his former girlfriend Élisabeth Bousquet, Djandoubi’s case unfolded against a backdrop of growing opposition to the death penalty in Europe. The execution, carried out in Marseille’s Baumetes Prison, marked the end of the guillotine’s nearly 200-year use in France and the Western world. This event sparked significant controversy, highlighting issues of justice for immigrants, the ethics of capital punishment, and the guillotine’s role as a symbol of state-sanctioned death. It contributed to the momentum for abolition, achieved in 1981 under Justice Minister Robert Badinter and President François Mitterrand. Examining this case objectively reveals the intersections of crime, migration, and penal reform, underscoring the importance of humane legal systems and the lessons from history in preventing the perpetuation of irreversible punishments.

Hamida Djandoubi was born on September 22, 1949, in Tunisia, into a modest family. He immigrated to France in 1968 at age 19, settling in Marseille, where he worked as a laborer in agriculture and landscaping. In 1971, he suffered a severe workplace accident, losing two-thirds of his right leg, which led to unemployment and reliance on disability benefits. This period marked a turning point, as financial struggles and personal frustrations contributed to his descent into criminal behavior. Djandoubi began relationships with several women, some of whom he coerced into prostitution to support himself.

The crime for which Djandoubi was convicted centered on Élisabeth Bousquet, a 21-year-old French woman he met in 1973. Initially a romantic relationship, it deteriorated as Djandoubi became abusive. He forced Bousquet into sex work, using violence to control her. On July 3, 1974, after Bousquet attempted to leave him and filed a complaint for assault, Djandoubi lured her to his apartment under the pretense of reconciliation. There, he subjected her to prolonged torture, including burning her with cigarettes on sensitive areas, beating her, and ultimately strangling her to death. He then disposed of her body in a rural area outside Marseille, where it was discovered weeks later.

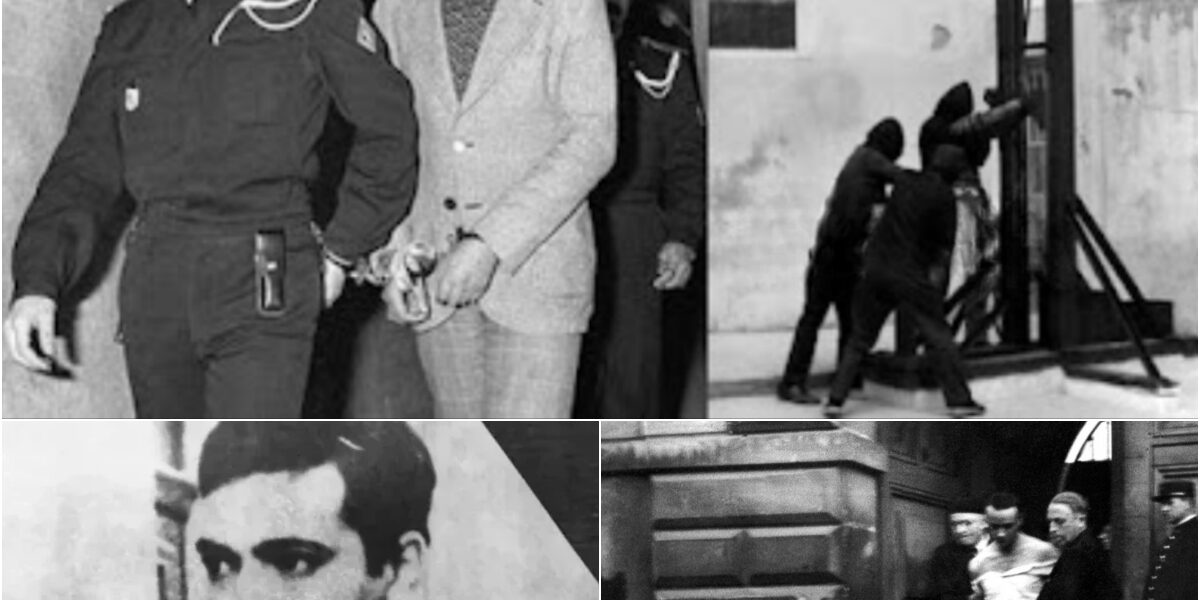

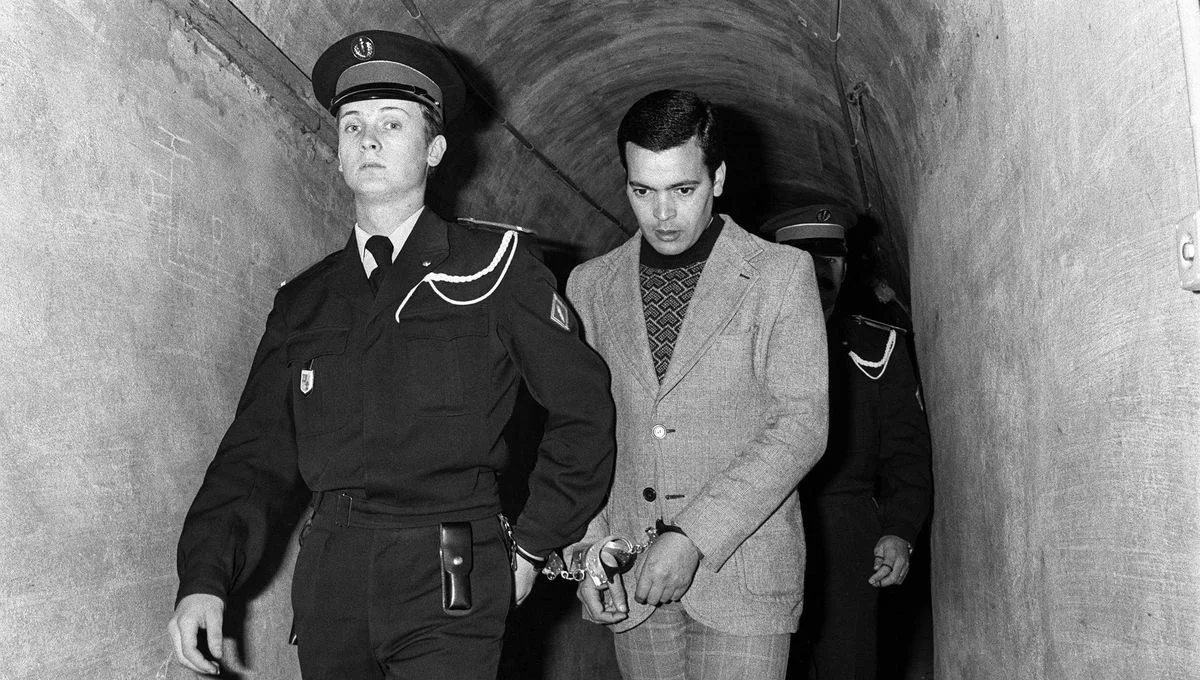

Djandoubi was arrested shortly after, following Bousquet’s disappearance and witness testimonies. During the investigation, two other women came forward, accusing him of similar acts of torture and coercion into prostitution. He was charged with murder, kidnapping, and aggravated assault. His trial in February 1977 at the Aix-en-Provence Assize Court lasted several days, with graphic evidence presented, including medical reports on Bousquet’s injuries. Djandoubi’s defense argued diminished responsibility due to his disability and psychological state, but the jury convicted him, sentencing him to death—the guillotine being France’s standard method at the time.

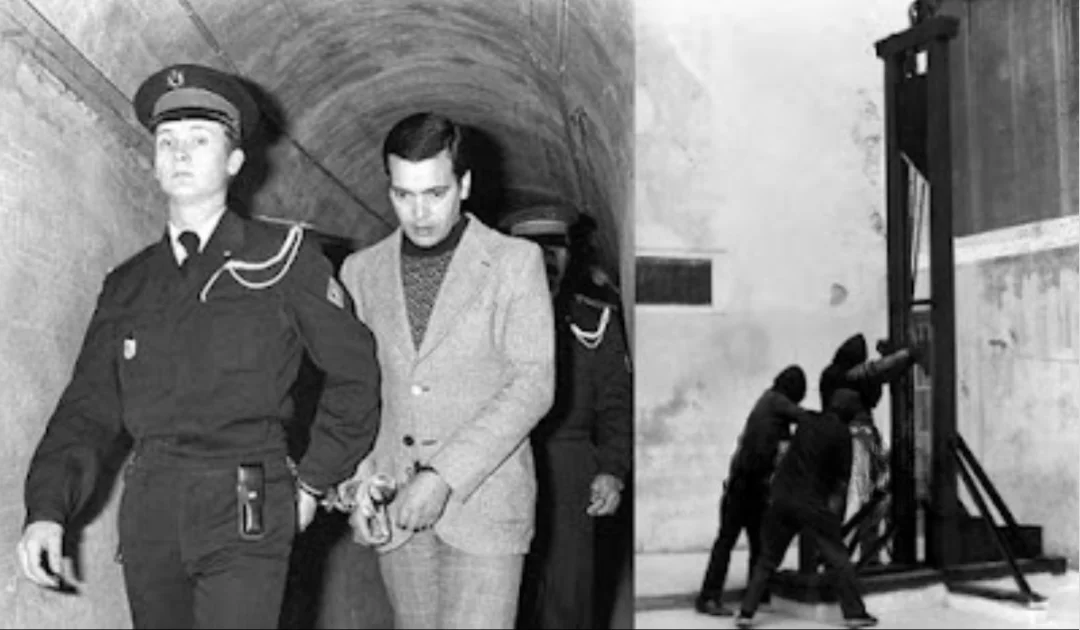

Appeals followed, but President Valéry Giscard d’Estaing denied clemency, influenced by the crime’s brutality amid public pressure for harsh penalties on violent offenders. On September 10, 1977, at 4:40 a.m., Djandoubi was executed in Baumetes Prison by chief executioner Marcel Chevalier. The process was swift, as per the guillotine’s design, but the case drew criticism: Djandoubi was a disabled immigrant, and anti-death penalty activists, including Badinter, argued it exemplified the penalty’s discriminatory application. Witnesses, like court clerk Monique Mabelly, later described the scene as dehumanizing, fueling abolitionist sentiment.

This execution was the last in France and the Western world using the guillotine, following Christian Ranucci (1976) and Jérôme Carrein (1977). It occurred amid debates on capital punishment’s efficacy and morality, with public opinion shifting due to concerns over miscarriages of justice and human rights. Badinter, appointed Justice Minister in 1981, spearheaded the abolition bill, passed on October 9, 1981, ending a practice rooted in the Revolution but increasingly seen as archaic.

The execution of Hamida Djandoubi, while concluding a chapter of violent crime, also marked the guillotine’s final use and accelerated France’s path to abolishing capital punishment. His case, involving severe offenses against a vulnerable victim, nonetheless raised questions about justice, immigration, and the state’s role in taking life. By studying this objectively, we recognize how such events propelled legal reforms, emphasizing rehabilitation over retribution and the irrevocability of death sentences. This history serves as a reminder of the need for equitable systems that protect victims while upholding human rights, encouraging societies to learn from past practices to build frameworks preventing crime through education, support, and fair adjudication rather than irreversible penalties.

Sources

Wikipedia: “Hamida Djandoubi”

History.com: “The guillotine falls silent | September 10, 1977”

Harper’s Magazine: “This Will Be the Last” by Monique Mabelly

Executed Today: “1977: Hamida Djandoubi, Madame Guillotine’s last kiss”

Wired: “Sept. 10, 1977: Heads Roll for the Last Time in France”

Amazon: “When the Guillotine Fell” by Jeremy MercerRealClearHistory: “

Official Record of the Last Beheading in France”

Additional historical references from academic sources on French penal history.