What should have been an ordinary summer day in a Glasgow neighborhood ended in a tragedy so stark and avoidable that years later it continues to shock even seasoned construction professionals, as an inquiry revealed that the manhole which claimed a 10-year-old boy’s life could have been made safe for the cost of loose change.

Ten-year-old Shea Ryan died on July 16, 2020, after falling more than 20 feet down an unsecured manhole shaft at a building site in the Drumchapel area of Glasgow, a site that experts now say was left dangerously exposed despite simple and cheap safety solutions being readily available.

The revelation came during a Fatal Accident Inquiry that has reopened deep wounds for Shea’s family and reignited public anger over how basic safety failures can have irreversible consequences.

Shea was just a child enjoying his summer, at an age when curiosity often outweighs caution and the world still feels like a place meant for exploration rather than danger.

Unbeknown to him, behind a fence that was easy to climb through, lay a construction site holding a hazard that even trained workers would approach with care.

That hazard was a manhole, known as MH22, positioned in an area called the Garscadden Burn Area, and covered only by a heavy metal lid that was not bolted, weighted, or secured in any meaningful way.

According to testimony heard at the inquiry, the lid weighed around 80 kilograms and could be pushed aside by two adult men, making it dangerously inadequate as a barrier to prevent access.

Plant operator Stuart Reid, an experienced digger driver who worked on the site, told the inquiry that while such lids were considered “standard,” they were far from safe when left unattended in an area that could be accessed by the public.

When asked what it would have taken to secure the lid properly, his answer stunned the courtroom.

“You could probably do it for a fiver,” he said, explaining that a simple trip to a hardware store would have been enough to buy bolts to fix the lid in place.

He added that drilling holes into the concrete and bolting the lid down would have taken roughly half an hour, a task so routine that it barely registered as extra work in the industry.

Other options were just as simple.

A ballast bag weighing several hundred kilos could have been placed on top.

A heavy iron road plate could have been laid over the opening in under a minute.

Any one of these measures, Reid said, would have stopped unauthorized access and drastically reduced the risk of a fatal fall.

None of them were used.

On July 16, 2020, Shea managed to climb through the unsecured fence surrounding the site.

Inside, the manhole sat waiting, its lid either partially displaced or easy enough to move aside.

At some point, Shea fell into the shaft, plunging more than 20 feet down into darkness.

He did not survive the fall.

The following morning, workers arriving on site were met with police tape and emergency vehicles, a scene that immediately signaled something had gone terribly wrong.

Reid told the inquiry that he first heard vague reports on the radio while driving to work, only learning the full horror once he arrived.

A child had died.

A boy.

Ten years old.

As the inquiry unfolded, it became clear that responsibility for the manhole had shifted shortly before the accident.

The manhole had been constructed by one company and then handed over to another as work on the site progressed.

Emails and photographs shown to the inquiry indicated that MH22 had been covered by a ballast bag shortly before the handover.

But when the new team took over, that bag was gone.

Reid testified that from the moment he began work on July 1, 2020, he never saw a ballast bag on MH22 or on any other manholes at the site.

“There was no ballast bag on MH22,” he told the inquiry plainly.

He also stated that no one on his team had any reason to access that manhole, as they were carrying out completely different work elsewhere on the site.

Despite this, no one replaced the ballast bag or took steps to secure the lid.

The inquiry heard that ballast bags are easy to source and can be filled with stone, gravel, or any heavy material to provide sufficient weight.

There was no logistical barrier.

There was no technical difficulty.

There was only inaction.

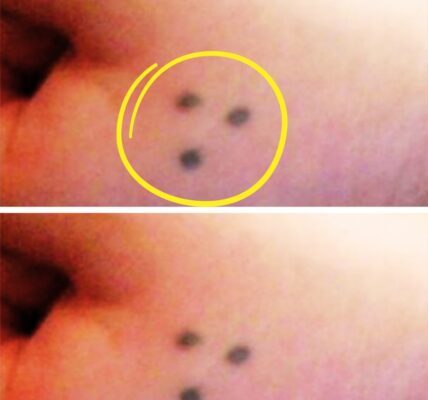

Photographs presented to the inquiry painted a chilling picture.

One image showed the manhole lid sitting half open, leaving a gap large enough for a person to fit through.

Another showed water at the bottom of the shaft, confirming it was what workers refer to as a “live manhole.”

Reid explained that the ladder inside the vertical shaft was made of hard plastic, which could become slippery, especially in wet conditions.

“If you slip or fall down there,” he was asked, “there’s a risk you fall into that water?”

“Yes,” he replied.

For trained workers, entering such a space requires certification and strict safety protocols.

For a child, there was nothing but danger.

Perhaps the most damning moment of the inquiry came when Reid was asked how the construction industry would view a manhole being left unsecured.

His answer was blunt and uncompromising.

“If somebody left it open, they should be sacked,” he said.

The words hung heavily in the room.

Because the manhole had been left unsecured.

And a child had died as a result.

Further evidence revealed that when the site changed hands, securing MH22 was never discussed or acted upon.

When questioned about why no action had been taken despite awareness of the manhole’s condition, a former assistant site manager admitted that it was not policy.

“It wasn’t considered,” he said.

That admission has since become a focal point of public outrage.

Not considered.

Not prioritized.

Not fixed.

All for the sake of a few pounds and a few minutes of time.

In the aftermath of Shea’s death, tributes poured in from across the community.

Flowers, cards, and messages were laid near the site, each one carrying a mixture of grief, anger, and disbelief.

Photos of Shea show a smiling boy with a bright future, a child who should have been worrying about school holidays and football, not navigating lethal hazards.

For his family, the pain has been constant and unrelenting.

Every new detail revealed by the inquiry is another reminder that Shea’s death was not the result of fate or bad luck, but of preventable failures.

Failures so small on their own, yet catastrophic when combined.

The case has sparked renewed debate about construction site safety, particularly in areas close to residential neighborhoods where children live and play.

Experts warn that unsecured manholes are a known risk, especially because heavy lids can be moved, displaced, or even stolen for scrap value.

That is precisely why additional safeguards exist.

And why ignoring them can be deadly.

As the Fatal Accident Inquiry continues, it is not just about understanding how Shea died, but about confronting the uncomfortable reality of how easily responsibility can be lost during transitions and handovers.

It raises urgent questions about accountability, oversight, and whether “standard practice” is good enough when lives are at stake.

Shea Ryan did not understand construction protocols, safety policies, or handover procedures.

He was ten years old.

He trusted that the spaces around him were safe enough to explore.

That trust was broken.

Years later, his name is spoken in courtrooms rather than classrooms, his life measured in evidence, photographs, and testimonies.

His death has become a stark lesson written in the harshest terms possible.

Sometimes, safety really does come down to the smallest actions.

A bolt.

A bag of stones.

Thirty seconds of effort.

For Shea, those seconds never came.

And the cost of that failure is one that can never be repaid.