How the strategic location of the diamond-shaped peninsula overwhelmed the Germans.

I. Introduction

The three principles of real estate are: “Location, location, location.” The size of the house, the price, the pool in the backyard: everything is important, but nothing is as important as the location of the house. Some locations are more desirable than others, and houses lucky enough to be built in one of these places are usually the subject of bidding wars.

It’s no different in military history. Some places simply seem to attract more attention, attract more invaders, and trigger more wars.

Take Crimea. The diamond-shaped peninsula high above the Black Sea has attracted hundreds of would-be rulers over the millennia. While it is a natural naval base, the tenuous connection to the mainland via the Isthmus of Perekop is just wide enough to attract land forces. And so it did, one after the other: Taurians and Scythians, Greeks and Romans, Byzantines and Kievan Rus’, Mongols and Ottomans and Russians, Soviet commissars and German field marshals. All were attracted by its beauty and temperate climate, but what really attracted them was its location. The ruler of the peninsula has a 360-degree projection of power at his disposal: to the north as far as Ukraine, to the east as the Caucasus, to the south as far as Asia Minor, or to the west as far as the Balkans.

“Take Crimea?” Many people have tried.

II. The Crimean War

The Crimean War of 1854–56 was a classic example of the lure of the peninsula. In December 1852, a diplomatic conflict arose between Russia and France over the status of some Christian shrines and churches in the Holy Land, then under Ottoman rule. Both powers claimed the right to protect the Christians living in the Ottoman Empire, with Russia representing the Orthodox believers and France the Roman Catholic population. To show his seriousness, the French Emperor Napoleon III sent a French ship of the line, the Charlemagne, to the Black Sea. The Ottoman Sultan Abdul Mejid was so impressed that he ruled in favor of France.

Russian protests against his decision fell on deaf ears in Istanbul, and in July 1853, Tsar Nicholas I ordered Russian troops to cross the border into the principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia (now Romania and Moldavia)—territories then still nominally under Turkish control. After Ottoman protests in St. Petersburg also fell on deaf ears, the empire declared war on Russia in October.

It’s easy to downplay this and highlight the obscure Monks’ Quarrel that triggered it all, but the stakes were high. The long-term trigger was the “Eastern Question,” the unrest in the Middle East caused by the decline of the Ottoman Empire. With Ottoman power seemingly waning, all the major powers wanted to protect their own strategic interests in the region. From the perspective of London or Paris, a direct war between Russia and the Ottomans would certainly have led to a decisive Russian victory, and Russian dominance in the Middle East was unthinkable. And so, British and French navies marched into the Black Sea to show their support for the Turks.

The situation escalated on November 30, when a Russian naval squadron operating from Sevastopol, the major naval base in Crimea, destroyed a Turkish squadron of thirteen ships off Sinope with its innovative explosive shells, causing approximately 4,000 casualties. Under enormous pressure from public opinion incited by the “barbarism” of this “Sinope Massacre,” Great Britain and France declared war on Russia in March 1854.

Their goal was to prop up the faltering Ottoman Empire, but that hardly seemed necessary. After the declaration of war, Turkish troops took the fight to the Russians, invading Wallachia and fortifying several positions along the Danube. The Russian advance south stalled, and in April 1854 they began a haphazard siege of the fortress of Silistra. The Ottomans held their ground, but unfortunately, an Allied expeditionary force was already at sea. It landed in Varna on the Black Sea in May, where poor sanitary conditions promptly sparked a cholera epidemic that killed thousands. At the same time, the Russians realized they would never take Silistra and abandoned the siege in June. Following an ultimatum from neutral Austria, they completely evacuated Wallachia and Moldavia.

The matter could well have ended here, but the Allies were in a war zone, and simply turning around and heading home would have been a public relations fiasco. They had to attack Russia somewhere. It had to be a prestigious and valuable target, nearby, and in a location vulnerable to Allied naval power. Given the region’s geography and strategic realities, there was only one solution: an attack on Crimea. The Allies would capture Sevastopol, punish the Russians for Sinope, and reduce the threat to the Ottoman Empire once and for all.

A force of five British and four French divisions dutifully sailed toward Crimea and landed at Eupatoria in September. Neither of the opposing armies had fought a serious war since 1815, and the impact was palpable. The Allies landed without transport and with little equipment except rifles, drove directly down the main road to Sevastopol, and encountered the Russians, who immediately blocked their path. There was no preparatory jousting, no attempt to find a flank, no real reconnaissance. On September 20, the opponents clashed at the Alma River.

It was the largest battle since Waterloo. Around 62,000 British, French, and Turks faced 35,000 Russians, but no one could cover themselves in glory at the Alma. The British and French began with a haphazard frontal assault. The Russians initially defended their entrenchments south of the river valiantly, but the Allies’ superior firepower, thanks to the new Minié rifle, soon forced them to retreat. The attack initially proceeded fairly orderly, but when their shaky leadership collapsed, it degenerated into a disorganized rout. Fighting far from home and with weak cavalry, the Allies could not mount a pursuit, and their victory ended in disappointment. The casualties, however, spoke volumes. The British had done the brunt of the attack, suffering 362 dead and 1,640 wounded. The French had difficulty climbing the cliffs in their sector of the battle and arrived late, suffering 60 dead and 500 wounded. The Russians fought in dense columns with smoothbore muskets and suffered over 5,000 casualties of all kinds.

The Russian defeat only ended in Sevastopol. The arriving force was more of a beaten rabble than a cohesive army, and the Allies could have easily captured the city with a swift assault. However, since this was a war of caution, the Allied command opted instead for a long flanking march around the city. This maneuver allowed them to capture new supply ports—Kamietch for the French and Balaklava for the British. They were forced to abandon their original base in Eupatoria, which had already been rendered untenable by the Cossack attacks.

A good idea, then, but one that also wasted valuable time. The Allies didn’t bomb Sevastopol until October 17, and by that point, any hope of a quick victory was gone. Instead, there was a siege, always long, difficult, and costly. It began with a new outbreak of disease that struck the expedition members—this time a combination of dysentery and cholera—and in late November, a violent winter storm struck, destroying their supply fleet. While such things happen in every war, in Crimea there was a new factor: the telegraph. It enabled correspondents like WH Russell of The Times of London to send daily reports with all the gruesome details to shocked readers back home. One of them was Florence Nightingale, owner of a London nursing home. With government support, she traveled to Crimea and performed miracles in reforming the structurally weak Allied medical service, becoming a war media star in the process.

On the ground, the Russians launched three unsuccessful attempts to relieve Sevastopol: in October at Balaklava (site of the attack by the British Light Brigade), in November at Inkerman Hill, and in August 1855 at the Chernaya River. The Allies repulsed each attempt with heavy losses, and the decision was final. Successive Allied bombardments of the fortress met increasingly weak resistance, and a French attack in September 1855 destroyed the main defensive position, the Malakoff Redoubt. Recognizing their defeat, the Russians fired their guns and abandoned the city.

By now, all the side agreements had been exhausted, and the subsequent Peace of Paris reflected this. The treaty returned Sevastopol to the Russians, as a long-term Allied occupation was politically and militarily unfeasible. At the same time, it demilitarized the Black Sea and prohibited the Russians from stationing fleets or armed forces in the war zone. But that was it, and even these tenuous clauses had a very short half-life. With Europe under pressure from the Franco-Prussian War of 1870/71, the Russians denounced the entire treaty.

The Crimean War, largely forgotten today, was a turning point in history for many reasons. The art of war took a quantum leap, with railways, rifles, and the telegraph taking center stage. Russia’s utter ineptitude—incapable of defending even a fortress on home soil—shocked the country. It led to long-overdue social reforms such as the abolition of serfdom, but it also fueled the rise of radical revolutionary groups that ultimately brought down the entire empire. Most importantly, the war demonstrated the importance of Crimea itself, then as ever a strategically vital territory. This time, the lure of the peninsula had summoned the soldiers of four great empires, killing over half a million of them.

III. World War II:

The same dynamic is evident in World War II. The war between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union was the largest land conflict in history. Both sides mobilized millions of soldiers, and the fighting raged from the Arctic Circle to the Caucasus. And yet, at times, it seemed as if Crimea had become the focal point of the entire gigantic struggle.

Here, too, it was a question of location. In short, neither side could advance beyond a certain point in Ukraine as long as Crimea was in enemy hands. The Germans felt the pull first. As Army Group South advanced at top speed on Rostov in the summer of 1941, Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt had to halt and divert an entire field army, the 11th, to capture Crimea. When the commander of the 11th, General Eugen von Schobert, had the misfortune of landing his Fieseler Storch in a freshly laid Russian minefield, General Erich von Manstein took command. He penetrated Crimea through the deeply echeloned Soviet defenses on the Perekop Isthmus, eyeing the great prize of Sevastopol.

Before he could get there, however, problems arose all over the map. Crimea’s central location is a double-edged sword: events in many different sectors can profoundly affect it. A Soviet counteroffensive on the northern coast of the Sea of Azov forced him to withdraw a corps to contain the offensive; the fall of Odessa in the west brought another evacuated Soviet division to Sevastopol. Although German intelligence reported three Soviet divisions on the peninsula, there were now at least seven.

As a result, the Germans had great difficulty evacuating Crimea and were not ready to storm Sevastopol until December. They had to break through three concentric rings of Soviet fortifications, including strongpoints, machine-gun emplacements, medium and heavy batteries in tank turrets, and positions built in caves and rocky slopes. They had come within a stone’s throw, but just as they were about to break through, Soviet reinforcements arrived in the form of the 79th Independent Naval Brigade. Dispatched to Severnaya Bay with a small flotilla, they hurried ashore, rushed into the threatened sector, and held back the onrushing Germans. The Soviet crisis over Sevastopol was over.

Now the Germans were in trouble. While Manstein pondered his failure, the Soviets launched an assault on the eastern side of Crimea with a series of amphibious landings on the Kerch Peninsula. Three entire armies landed (51st, 44th, 47th), and the Soviet commander, General D.T. Kozlov, then hurled them at the German defenses in the Parpach Pass. Four times he sent them forward, four times they staggered back with massive losses. The final attempt in April was particularly gruesome: tanks, guns, and trucks became bogged down in the sticky mud, and the men had to carry the grenades forward by hand.

Kozlov had failed, and once again Manstein had the advantage. His response was Operation Trappenjagd (“Bustard Hunt,” named after the flightless bird that inhabits Crimea). The Soviet offensives had petered out, with slight successes in the northern sector, a spur advancing toward the German lines. Manstein, smelling blood, launched an attack on May 9. He deployed the 33rd Corps in the north to pin down the Soviet forces and let the reinforced 33rd Corps take over the main offensive in the south, breaking through the Soviet front and clearing a path for the 22nd Panzer Division. Once through, the Panzers swung sharply left, drove north, and penetrated the rear of the Soviet 51st and 47th Armies in the coastal spur, cutting off their path and encircling them. Throughout the offensive, the German Air Force was the superior air force; Virtually the entire 4th Air Fleet was stationed in Crimea. Normally tasked with supporting an entire army group, it flew thousands of sorties daily over this tightly confined battlefield. Soon, the encirclement transformed into a seething cauldron of fire and destruction. Kerch itself fell on May 16, the eighth day of the operation. After two more days of mopping up, the bustard hunt was over. Soviet losses were colossal: some 170,000 men, over 1,100 guns, and 250 tanks; the Germans, by contrast, had lost only 7,500 men.

Nevertheless, Sevastopol held firm. Russian skills in siege and field fortification were legendary, and the fortress’s defenders (the 1st Independent Coastal Army) had been busy in the final months. New strongpoints, bunkers, and tank traps were built along the perimeter, and key sections such as the northern shore of Severnaya Bay boasted some of the most heavily fortified concrete blockhouses in the world. Among the most important defenders were the monstrous twin fortresses “Maxim Gorky I” and “Maxim Gorky II,” each containing two heavily armored turrets, each mounting two 305 mm guns. Superlatives are always difficult to prove, but Sevastopol may well have been the strongest fortress in the world in 1942.

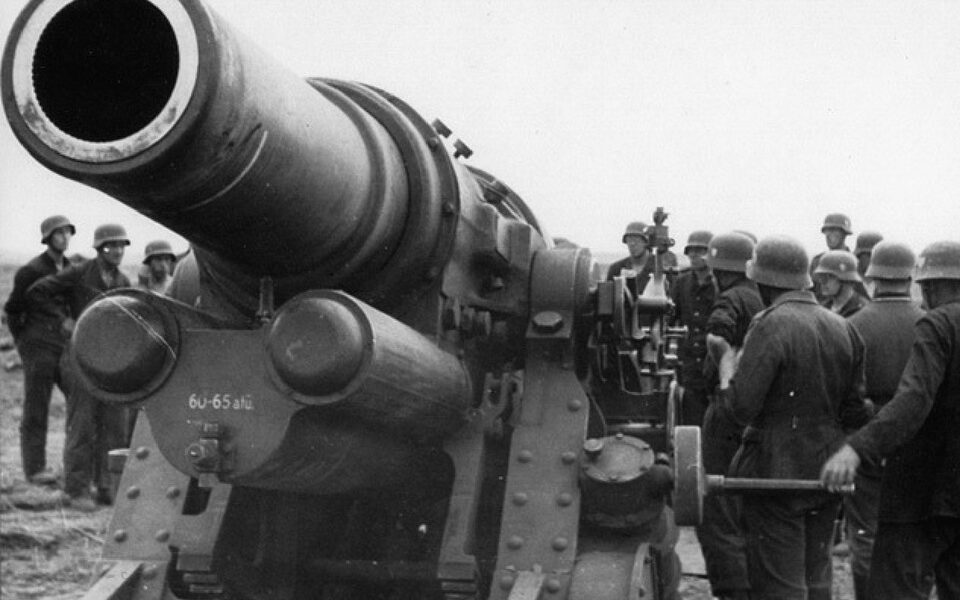

Manstein, however, had a ready answer: a salvo of “annihilating fire.” By the beginning of June, he had made his entire air force operational, and at the front, guns of all kinds were disarmed. Among them were the monsters of the German arsenal, guns so large they still fascinate today: two 600 mm guns (“Karl”) and “Dora,” the world’s largest artillery piece with an 800 mm bore and a 27-meter-long barrel. It was a “crew-arms weapon” with a crew of 2,000 men.

The bombardment began on June 2. 600 ground support aircraft and 611 guns crowded together on a front just 35 kilometers wide. Sevastopol transformed into a “sea of flames,” as the German air commander described it, and remained so for a month. A single shell from Dora, for example, destroyed an entire ammunition depot constructed from 27 meters of thick rock on the northern shore of Severnaya Bay. Not even the underground tunnels connecting these positions, which sheltered the civilian population during the fighting, offered sufficient protection.

With this enormous weight of metal behind them, the Germans broke through the Soviet defenses, with the LIV Corps advancing to the north and the XXX Corps to the southeast. Between them, the Romanian Mountain Corps—superb troops—carried out a holding operation. Soviet resistance was stubborn, and losses were heavy on all sides, but by June 13, the Germans had reached the northern shore of Severnaya Bay. Manstein again recognized an opportunity—his operational talent—and now devised an elegant maneuver to unhinge the Soviet defenses. On the night of June 28-29, elements of the 50th Infantry Division carried out a daring amphibious crossing of Severnaya Bay on 100 assault boats, capturing the steep southern shore in their first assault. During the day they overran the Inkerman Ridge and the old Malakoff Bastion, positions that had been so crucial to the city’s defense in 1855.

Manstein’s stroke had severely damaged Sevastopol’s inner defensive ring and sealed the fortress’s fate. The 11th Army stood at the gates, and air and artillery fire continued to tear away the rubble. Late on June 30, Soviet commanders in Sevastopol received evacuation orders—too late, as it turned out. Many Soviet soldiers were needlessly taken prisoner. The Germans marched into the city on July 1.