The Eastern Front: German Strategic Planning, 1942

Germany’s need for oil was a key factor in Hitler’s decision to invade Russia in 1941: Operation Barbarossa, which began on June 22, involved 3.8 million Axis troops—the largest military invasion in history. But after Barbarossa failed in the winter of 1941 and Soviet counteroffensives eliminated the immediate threat to Moscow, oil remained crucial to German strategy for the following year.

In September 1939, German oil reserves amounted to 842,000 tons. The subsequent conquest of large parts of Western Europe added another 280,000 tons of oil, and imports from the Soviet Union added another 225,000 tons. However, a study from May 1941 showed that reserves would be exhausted by August of that year, as military demand exceeded imports and domestic production.

The Soviet exploitation of the 1939 German-Russian Non-Aggression Pact to annex the Romanian provinces of Northern Bukovina and Bessarabia posed a direct threat to the Romanian Ploesti oil fields, which were crucial to the German war effort. As early as July 31, 1940, Hitler informed the top commanders of his intention to “smash Russia to its core with one blow.” He also emphasized the need to capture the Baku oil fields in present-day Azerbaijan: These were the richest in the Caucasus (between the Black and Caspian Seas) and among the most productive in the world.

The failure of Barbarossa to knock Russia out of the war prompted Hitler to make the conquest of the Caucasus oil fields his top priority for 1942. To achieve this goal, German planners developed “Fall Blau,” a three-stage offensive:

Blue I : The 2nd Army and the 4th Panzer Army under the command of Hermann Hoth, supported by the 2nd Hungarian Army, were to attack from Kursk towards Voronezh on the upper Don and protect the northern flank of the offensive towards the Volga.

Blue II : The 6th Army, under Friedrich Paulus, was to attack from Kharkov and advance parallel to the 4th Panzer Army to reach the Volga at Stalingrad. (Initially, the city was considered only a secondary objective—Hitler’s Directive 41 stated: “Every effort will be made to reach Stalingrad itself, or at least to bombard the city with heavy artillery so that it is no longer usable as an industrial or communications center.”)

Blue III : The 1st Panzer Army would advance south towards the lower Don, flanked by the 17th Army to the west and the 4th Romanian Army to the east, thus clearing the way for an advance into the Caucasus.

The Panzer divisions deployed for the offensive were reinforced by tanks from other sectors, each with three Panzer battalions. The heavy German losses since the beginning of Barbarossa necessitated the deployment of foreign troops. A total of 52 divisions were deployed – 27 Romanian, 13 Hungarian, 9 Italian, 2 Slovak, and one Spanish volunteer division.

Although 1,100,000 replacement troops were sent to the Eastern Front between June 22, 1941, and May 1, 1942, the average strength of the infantry divisions of Army Group South was approximately 50%, while that of the other two army groups was only 35%. Army Group South was given priority: its infantry units were to reach full strength by the start of the offensive in 1942.

The strategic targets of the operation were the Caucasus oil fields of Maikop, Grozny, and Baku—they together accounted for 84% of Soviet production. On June 1, 1942, four weeks before the offensive, Hitler declared to his senior officers: “If I don’t get the oil from Maikop and Grozny, I must end this war.”

However, it appears that he never seriously considered the practical possibilities of transporting oil to the Reich. A special unit, the Caucasus Mineral Oil Brigade, was formed to develop captured oil fields. However, when it reached Maikop in August 1942, it found that Soviet sabotage was so extensive that fewer than 1,000 tons of oil could be extracted before the Germans were forced to withdraw in January 1943.

Stalin’s problems

Despite the defeat of the final German offensives in 1941, Stalin was well aware of the continuing threat posed by the Axis powers—by early 1942, the Red Army had lost over 6,127,000 men, almost 50% of whom were taken prisoner. Although Axis losses during this period totaled 850,000 of the 3,800,000 men originally committed to Barbarossa, Russian losses were about seven times higher.

While Hitler saw the German economy under pressure, the Soviet economy was in a far worse situation. Despite Red Army counteroffensives, the Germans still controlled the regions that had supplied the majority of Russia’s key raw materials, including iron ore and manganese. By early 1942, the Reich was producing around 80% more coal and 70% more steel than the Soviet Union. At that time, the Caucasus was one of the few sources of oil and raw materials accessible to Stalin—but the German offensives of 1941 had overrun 40% of the Soviet railway network. This loss, combined with the damage inflicted by the Luftwaffe, threatened to disrupt vital supplies from the Caucasus.

Another strategic factor was anti-Soviet uprisings in the region: in early 1942, a major uprising that began in Chechnya and Ingushetia spread to neighboring Dagestan. German intelligence services quickly began to exploit the situation—presumably, both the Abwehr (military intelligence agency) and the SS were involved in the establishment of several “National Committees” composed of émigrés, defectors, and prisoners of war, intended to act as governments-in-exile for various ethnic groups in the Caucasus. Regiment-sized “legions” were established from the same sources to provide these committees with at least symbolic forces and to provide local knowledge to the German formations spearheading the planned advance.

Could “Operation Blue” have worked? In retrospect, it’s easy to dismiss the plans as unrealistic, yet they came remarkably close to success. Hitler’s failure was largely due to his disregard for the basic military principle of “objective maintenance”—his growing obsession with capturing Stalingrad was arguably the factor that doomed the campaign. Had he given absolute priority to capturing the oil fields, the war on the Eastern Front might have ended very differently.

The Second Battle of Kharkov: May 12–28, 1942

The origins of this significant battle date back to January 1942, when the Red Army launched the Barvenkovo-Lozovaya Offensive, one of several winter counteroffensives to recapture large swathes of Axis-held territory. It was a highly ambitious operation by the Soviet army groups of the Southwestern and Southern Fronts. The objective was to recapture the Ukrainian city of Kharkov before advancing into the rear of the German Army Group South in the Donbas-Taganrog area. Although the Red Army succeeded in destroying three German infantry divisions, the offensive failed to achieve its overall objectives. This was primarily because the German strategy of building a defensive network of fortified towns and villages drastically slowed the Soviet advance. Crucially, the successful defense of two key cities, Balakleya and Slavyansk, diverted the Soviet advance into the so-called “Barvenkovo Front” or “Izyum Bulge,” where it was finally halted in late January, having advanced 80 km deep and 115 km wide.

Mutual exhaustion and the thick mud of the spring thaw forced a pause in major operations, giving both sides a chance to plan their summer campaigns. While Hitler was determined to concentrate German efforts on capturing the Caucasus oil fields, Stalin feared that the reinforcements of Army Group South indicated preparations for a renewed assault on Moscow using an indirect approach. The fundamental problem was whether to forestall the German offensive or pursue a defensive strategy until the Red Army had rebuilt its strength. The more thoughtful senior officers—notably Marshal Shaposhnikov, Chief of Staff of the Stavka, the Soviet High Command—realized that the Soviet counteroffensives had succeeded only because the Germans were ill-equipped for war in the exceptionally harsh winter. Stalin, however, was fixated on the danger to Moscow and ordered Marshal Timoshenko to prepare an attack to recapture Kharkov in order to disrupt German preparations for an offensive of their own. These goals were ambitious enough, but Timoshenko soon expanded them to include the recapture of a large swath of territory as far as the Dnieper. Stavka’s planning staff feared that the offensive could be dangerously overstretched, but Stalin angrily dismissed these concerns, asking: “Should we remain on the defensive… and wait for the Germans to attack first?”

Due to weaknesses in the Soviet command, particularly the lack of a deception plan, German intelligence was able to detect the buildup of Soviet forces and came up with a fairly accurate estimate of 750,000 men, 1,000 infantry fighting vehicles, 10,000 guns and mortars, and 400 aircraft. The bulk of the tanks were concentrated in tank brigades, which in most other armies were barely equivalent to a tank battalion, each with a nominal strength of 10 KV-1 heavy tanks, 20 T-34 medium tanks, and 20 T-60 light tanks. Shortly before the offensive, some of these brigades were consolidated into tank corps, each of which was supposed to have 100 tanks. In fact, Timoshenko fielded 923 tanks, one-third of which were modern heavy and medium tanks (80 KV-1s and 239 T-34s). There were also 117 British Matilda II and 81 Valentine tanks suitable for infantry support. However, the remaining Soviet armor consisted of a mix of low-combat T-60 light tanks, along with obsolete T-26, BT-2, and BT-5 light tanks in some tank brigades. The extent of the damage inflicted on the Red Army since June 1941 was demonstrated by the fact that only six of Timoshenko’s 19 tank brigades were fully equipped. In the sectors selected for the main thrusts, the Soviets had, at best, a numerical superiority of 3:1 in tanks and infantry and 2:1 in artillery. The tank formations had a significantly higher proportion of medium tanks than the Soviet tank brigades, in particular the 112 Pz.IIIJ and 17 Pz.IVF2 (armed with long-barreled 50 mm and 75 mm cannons), which gave them the opportunity for the first time to compete with the T-34 on a nearly equal basis.

Initially, the Soviet Air Force enjoyed significant numerical superiority over the Luftwaffe in this sector. It commanded a total of 142 Yak-1, LaGG-3, and MiG-3 fighters, 85 Su-2 and Pe-2 light bombers, 67 Il-2 Shturmovik ground-attack aircraft, and 125 Po-2/U-2 biplane night bombers. In contrast, the IV Air Corps commanded only 40 Bf-109F fighters and 60 He-111H bombers. However, the Soviets’ numerical superiority was largely offset by poor aircraft production standards and inadequate crew training, which led to massive losses. (In 1942, the Russians fielded a total of 33,000 aircraft, losing 7,800 in combat and another 4,300 in accidents.) Any remaining Soviet advantage was wiped out when a large portion of Fliegerkorps VIII was hastily withdrawn from the Crimea, including 43 of the new Hs 129 anti-tank aircraft, over 100 Ju 87 dive-bombers, 144 Bf 109F fighters, and 170 Ju 88 bombers. These reinforcements began arriving on May 14, allowing the Luftwaffe to quickly regain air superiority and German bombers to conduct virtually unhindered attacks on battlefield targets and Soviet supply lines.

Timoshenko planned to launch the northern pincer line of his offensive with the 21st, 28th, and 38th Armies from the Staryi Saltiv bridgehead east of Kharkov. The southern pincer line was to begin with the 6th, 9th, and 57th Armies in the Barvenkovo Salient. After breaking through the German front, the 6th Army was to deploy a mobile group based on the newly formed 21st and 23rd Panzer Corps to encircle the German 6th Army from the south. The breakthrough of the northern group was to be exploited by the 3rd Guards Cavalry Corps, and it was assumed that the Soviet pincer line would converge within 15 days. Timoshenko formed Army Group Bobkin on April 27 using assets from the 6th Army to provide combined-arms flank protection for his main operation. However, this only resulted in the blurring of command responsibility in the Barvenkovo Salient, which was already divided between the 6th Army of the Southwestern Front and the 9th and 57th Armies of the Southern Front.

While Tymoshenko was planning his offensive, the Germans were preparing their own attack, codenamed “Unternehmen Fridericus” (Operation Friedrich), which was intended to serve as a prelude to the main attack, “Fall Blau” (Case Blue), against the oil fields in the Caucasus. It was intended to be a simple offensive with two concentric thrusts that would meet at Izyum and cut off the Barvenkovo salient. Originally planned for mid-April, Fridericus was postponed to May 18 to allow sufficient time for troop concentration – but Tymoshenko’s attack thwarted the operation.

The fight begins

The Russian offensive began on May 12 with a 60-minute artillery barrage and achieved initial successes due to its numerical superiority. However, after advancing an average of 25 km in the first 48 hours, Timoshenko was unable to maintain the pace of the offensive. The northern offensive arm lost momentum while attempting to break through the network of German strongpoints. It was subsequently met with a counterattack led by the 3rd and 23rd Panzer Divisions. On May 17, the 3rd Guards Cavalry Corps had to be deployed to prevent a complete collapse in this sector.

The southern offensive also initially made good progress but failed to achieve a complete breakthrough. However, it did open gaps in the German front, allowing the 6th Cavalry Corps to advance to the important railway junction of Krasnograd by May 16. The situation was critical, but an ad hoc combat group, the Ziegelmayer Blocking Unit, consisting of an engineer battalion and a motley crew of rearguard troops, was able to repel the Soviet cavalry, which lacked the manpower and heavy weapons to break through even the improvised defenses.

It became apparent that the Red Army was still no match for German tactical flexibility. One tank officer recalled how Soviet tank units “got in each other’s way and were thwarted by our anti-tank guns… Back then, individual 88s could disable more than 30 Soviet tanks in an hour. We thought the Russians had created a tool they would never be able to properly handle.”

Nevertheless, the Soviet forces continued to advance on May 17, when the 1st Panzer Army, under Colonel-General Ewald von Kleist, with a total of nine divisions, including the 14th and 16th Panzer Divisions, launched a devastating counteroffensive against the southern flank of the Barvenkovo Salient. It defeated the Russian 9th Army within 24 hours and further disrupted the Soviet command structure on May 18 when it overran the headquarters of the 57th Army. At the same time, the 16th Panzer Division captured Izyum, cutting off one of the most important Russian supply lines across the Donets River near Donetsky.

Timoshenko hesitated for several hours before informing headquarters of the situation late on May 17. Colonel General Vasilyevsky, the acting Chief of Staff at headquarters, realized that the Germans intended to cut off the Barvenkovo Salient and recommended halting the offensive to free up forces that could stop Kleist. However, Stalin ordered Timoshenko to continue the attack on Kharkov while simultaneously deploying the 21st and 23rd Panzer Corps to prevent a German breakthrough. When they finally redeployed their forces 48 hours later, Kleist was already threatening Protopopovka, a vital communication line and one of the last important Soviet-held border crossings on the Donets.

On May 19, Vasilevsky finally persuaded Stalin to abandon the attempt to capture Kharkov and instead focus on defeating Kleist. However, constant Luftwaffe attacks thwarted Timoshenko’s attempts to regroup his troops, whose mobility and combat effectiveness were also hampered by a lack of fuel and ammunition. By May 21, the narrows of the Barvenkovo Salient had been reduced to just 18 km and were completely closed the following day by a final German assault. Such a large proportion of the Red Army’s armored forces were committed to the offensive that virtually no tanks were available to break through the German cordon and rescue Timoshenko’s troops, who were desperately trying to escape the encirclement. On May 25, the remnants of four encircled divisions launched a major offensive that was bloodily repulsed. However, further escape attempts became increasingly disorganized as the command structure within the pocket collapsed. By May 26, over 200,000 Soviet soldiers and hundreds of vehicles were concentrated in a 20-kilometer-wide strip of the Bereka Valley, where they were bombarded by German artillery and subjected to repeated air raids. The Luftwaffe (especially Luftflotte IV) played a decisive role in the German victory, flying 15,648 sorties (an average of 978 per day) and dropping 7,700 tons of bombs.

The Red Army’s personnel losses probably totaled 170,000 killed, captured, or missing, and 106,000 wounded. Twenty-two rifle divisions, seven cavalry divisions, and 15 tank brigades were destroyed. Equally severe were the losses of equipment: 1,200 armored personnel carriers, 1,600 guns, 3,200 mortars, and 540 aircraft. Equally serious was the widespread destruction of the commanders and staffs of the 6th, 9th, and 57th Armies, which further exacerbated the already severe shortage of qualified staff officers.

The Kharkov disaster clearly demonstrated the fragility of the Red Army at this stage of the war. Its ranks were filled with poorly trained conscripts, and the officer corps, decimated by Stalin’s purges, struggled to learn the basics of tank warfare while fighting a highly sophisticated enemy.

Semyon Konstantinovich Timoshenko (1895–1970) was the son of a peasant family. In 1915, he was drafted into the Imperial Russian Army and served in the cavalry. In 1918, he joined the Bolsheviks and fought throughout the Russian Civil War in the 1st Cavalry Army. There, he first met Stalin, who was then Commissar of the Red Army. Stalin’s patronage ensured his steady promotion and survival during the purges of the late 1930s. Timoshenko commanded the Soviet forces that overran eastern Poland in 1939 and subsequently forced the Finns to surrender after the Red Army’s humiliating defeats in the early stages of the Winter War. In May 1940, in recognition of his role in the victory over Finland, he was promoted to the Red Army’s highest rank—Marshal of the Soviet Union—and became People’s Commissar of Defense. After the German invasion, Stalin sent Timoshenko as a “firefighter” to salvage as much as possible after the series of Soviet defeats in the summer and autumn of 1941. Despite the magnitude of the Kharkov disaster, he was given command of the Northwestern Front in July 1942. Although he had served primarily in the cavalry before the war, Paul Ludwig Ewald von Kleist (1881–1954) quickly demonstrated an innate talent for armored warfare. He commanded Panzergruppe Kleist (later the 1st Panzer Army), the first operational grouping of several Wehrmacht armored corps in the Battle of France. Among the units under his command in this campaign were the five Panzer divisions that participated in the Ardennes attack, which was decisive for the final German victory. During Operation Barbarossa, Kleist’s 1st Panzer Army destroyed 20 Soviet divisions in the opening phase of the offensive and participated in the destruction of another 50 divisions in the Kiev pocket. Following his brilliant victory at Kharkov, he commanded Army Group A in its advance to the oil fields of the Caucasus. Following the Axis defeat at Stalingrad, he led a remarkably successful withdrawal from the region, but growing disagreements with Hitler led to his dismissal in March 1944. After the war, Kleist was extradited to the Soviet Union, where he was sentenced to 25 years in prison for war crimes; he died in the Vladimir prisoner of war camp.

The Siege of Sevastopol: October 30, 1941 – July 4, 1942

The original plan for Barbarossa assumed that Crimea would be a secondary target after the destruction of the Red Army west of the Dnieper. However, in July 1941, Russian aircraft bombed Romanian oil refineries from Crimean airfields, destroying 12,000 tons of oil. This stark demonstration of the threat posed by Soviet control of Crimea prompted Hitler to order the conquest of the region in an addendum to Führer Directive 34 of August 12, 1941.

The need to eliminate the four Soviet armies, totaling nearly 50 divisions, encircled in the vast Kiev Pocket delayed the start of the assault on Crimea until September 24, 1941. Colonel-General Erich von Manstein’s 11th Army made good progress along the main route to Crimea via the Perekop Peninsula, but then had to divert troops to repel a Soviet counterattack near the Ukrainian city of Melitopol. The Germans were not able to resume their offensive until mid-October, by which time the defenders had been reinforced by 80,000 men evacuated by sea from Odessa. In just over a week of bitter fighting, Manstein broke through the remaining defenses and, by November 17, cleared all of Crimea, except for the heavily fortified naval base at Sevastopol. Initial attempts to storm the port between November 11 and 21 failed after parts of the outer defenses were overrun. Further attempts in December made only limited progress before being halted by Soviet reinforcements.

The situation changed dramatically on December 26, when the Russians launched an unusually resourceful amphibious operation across the narrow Kerch Strait, followed by further landings in the port of Feodosia. This forced the Germans to evacuate eastern Crimea and establish a new north-south defensive line across the Parpach estuary. Headquarters rapidly reinforced the area and, on January 28, 1942, created the Crimean Front under Lieutenant General Dmitry Kozlov. It consisted of the 44th, 47th, and 51st Armies, commanding the Independent Coastal Army (garrisoned in Sevastopol) and the Black Sea Fleet.

By early May, the Crimean Front numbered nearly 250,000 troops, supported by 350 tanks and over 400 aircraft. Kozlov had little combat experience beyond the regimental level and, like all other soldiers, feared the NKVD, the Soviet secret police. The malign influence of this organization was embodied by Lev Mekhlis, the Stavka representative on the Crimean Front, who was also head of the Red Army’s Main Political Directorate. He was an incompetent, arrogant tyrant who quarreled with Kozlov and brought about the dismissal of his capable chief of staff, the future Marshal Tolbukhin. Mekhlis persisted with repeated, ill-prepared attacks that undermined Soviet troop strength and was largely responsible for the failure to destroy the 11th Army when it was at its most vulnerable in early 1942. When Manstein launched a counterattack on May 8—codenamed Operation Trappenjagd—Mekhlis’s incompetence contributed to the destruction of the Crimean Front in barely ten days. As at Kharkov, there was little coordination between the Soviet tank brigades, whose 350 IFVs were deployed piecemeal. This negated their numerical superiority over the sole German armored formation, the undermanned 22nd Panzer Division, largely equipped with outdated Panzer 38(t) tanks. Once again, Soviet losses were staggering: the 44th, 47th, and 51st Armies, a total of 21 divisions, were annihilated, and the Germans took 170,000 prisoners and captured 258 tanks and over 1,100 guns.

After the last Soviet forces in Eastern Crimea were destroyed on May 20, 1942, Manstein was able to concentrate on capturing Sevastopol, which had been besieged by General Erick Hansen’s LIV Corps during the Bustard Hunt. Under the overall command of Vice Admiral Filipp Oktyabrsky, Commander-in-Chief of the Black Sea Fleet, Sevastopol’s garrison consisted of Major General Ivan Petrov’s Independent Coastal Army, with approximately 110,000 men in seven infantry divisions and one dismounted cavalry division, as well as an Independent Tank Battalion. They were supported by 6,000 men from three marine brigades, while two additional infantry brigades totaling 3,000 men had landed during the battle. The port’s three defense lines were impressive, comprising 3,600 permanent and improvised fortifications with 600 guns, including eight 305 mm guns in four twin turrets, and 40 tanks. Other permanent defenses included 33 km of anti-tank ditches, 56 km of barbed wire, and 9,600 mines.

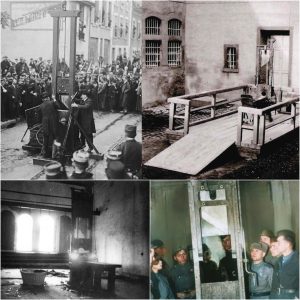

Although Manstein had nearly 204,000 men at his command for the assault, dubbed “Störfang,” he was severely short of infantry. To compensate for this, the 11th Army was assigned a total of 16 engineer battalions—each with 385 men, equipped with flamethrowers, mine detectors, and demolition charges. In addition, the 300th Panzer Battalion deployed a significant number of the new Goliath remotely controlled demolition vehicles for attacks on key strongpoints. Manstein planned to minimize infantry losses by deploying the firepower of his siege train of approximately 700 artillery pieces, including three 60 cm Karl self-propelled howitzers, one 80 cm Gustav railway gun, and 24 rocket launcher batteries.

The Luftwaffe provided generous air support, comprising a total of 600 aircraft from Colonel-General Wolfram Freiherr von Richthofen’s VIII Air Corps (seven bomber groups, three dive-bomber groups, and four fighter groups). The air and artillery assault began on June 2. Luftwaffe formations were deployed within 70 km of Sevastopol and could fly multiple missions each day. In the first 24 hours, 723 sorties were flown, dropping 525 tons of bombs throughout the city. Despite heavy anti-aircraft fire, only a single Stuka from StG 77 was lost, and intensive air support continued with a further 1,783 sorties between June 3 and 5. By the start of the ground offensive on June 7, the Luftwaffe had flown 3,069 sorties, dropping 2,264 tons of bombs and 23,800 incendiary bombs. The outdated Polikarpov I-15s, I-153s, and I-16s of the 62nd Fighter Brigade of the Black Sea Fleet defending Sevastopol were hopelessly outgunned by the Bf-109Fs of the VIII Air Corps escorting the bombers. Overall, the Germans lost only 31 aircraft (mostly to anti-aircraft fire) during the siege in a total of 23,751 sorties, dropping 20,000 tons of bombs.

While the majority of VIII Air Corps was busy bombing the city and its defenses, II/KG 26 focused on disrupting the Soviet naval supply lines. Although its He 111 torpedo bombers sank the tanker Mikhail Gromov, it quickly became clear that naval support would be necessary to prevent the Black Sea Fleet from reinforcing and resupplying the garrison.

An urgent request for Italian assistance led to the deployment of the 101st Flottiglia MAS, with nine motor torpedo boats (MTBs) and nine coastal submarines under the command of the highly competent Capitano di Fregata Francesco Mimbelli. The squadron was based in Feodosia and Yalta. It suffered its first losses on June 13, when Soviet MTBs, supported by fighter-bombers, sank the submarine CB-5 off Yalta. However, on June 18, MTB MAS-571 intercepted and dispersed a convoy of barges carrying reinforcements to Sevastopol before torpedoing and sinking the Black Sea Fleet submarine ShCh-214 off Cape Ai-Todor. Further Italian successes included the sinking of the 5,000-ton steamer Abkhazia and the damage to the 10,000-ton transport Fabritius, which was subsequently destroyed by Stuka dive-bombers. In the final phase of the siege, the Italians were reinforced by a squadron of German speedboats, which sank the Soviet gunboats SKA0112 and SKA0124 as they attempted to evacuate high-ranking officers from Sevastopol.

Erich von Manstein

Erich von Manstein (1887–1973) (above) served in the First World War as an infantry and staff officer, demonstrating such outstanding ability that he was one of only 4,000 officers to survive from the tiny postwar Reichswehr. Promoted to lieutenant general in 1939, he planned the Sichelschnitt (Sickle Cut) Plan, which contributed significantly to the defeat of France in the summer of 1940. During Operation Barbarossa, he commanded the 6th Panzer Corps in its advance from East Prussia toward Demyansk. In September 1941, he was appointed commander of the 11th Army and tasked with capturing Crimea and the naval base at Sevastopol. By November 1941, he had captured most of Crimea and repelled subsequent Soviet landings on the Kerch Peninsula. His capture of Sevastopol led to his promotion to Field Marshal and command of Operation Winter Storm, the unsuccessful breakthrough to the 6th Army at Stalingrad. Despite this failure, he planned the highly successful Kharkov counteroffensive, which inflicted heavy losses on the Red Army and stabilized the front. He became increasingly disillusioned with Hitler’s patchy conduct of the war and was dismissed as commander of Army Group South in March 1944. In 1949, he was sentenced to 18 years in prison for war crimes, but served only four years before being released in 1953.

Air superiority

The ground offensive finally began on June 7, slowly fighting its way through the port’s outer defenses. Goebbels’ propaganda made much of the Gustav and Karl super-heavy siege artillery, but although their three- and five-ton shells were capable of destroying the heaviest fortifications, their accuracy and range were shamefully poor, and no more than 170 rounds were available. Conventional artillery concentrated on destroying the pillboxes in each defensive perimeter—these consisted mainly of earth and wooden structures, vulnerable to the 15 kg and 43 kg HE shells fired by the 105 mm and 150 mm divisional howitzers. The Luftwaffe’s air superiority freed up 88 mm anti-aircraft batteries for use against particularly stubborn strongpoints, along with 37 mm and 20 mm anti-aircraft guns, which were highly effective at eliminating machine gun emplacements.

Some sectors of the front soon resembled the battlefields of World War I. This was particularly true of the Balaklava Front, where steep hills and rugged terrain forced the Germans and the Romanian Mountain Corps to conduct targeted infantry attacks on Soviet trenches. In other sectors, however, the 65 StuG III assault guns of Sturmgeschütz Battalions 190, 197, and 249 proved invaluable in minimizing German infantry losses and countering the 40 outdated T-26 light tanks of the Soviet garrison’s 81st Tank Battalion.

By the end of June, the situation was virtually deadlocked, with both sides suffering heavy losses. However, Manstein saw an opportunity to break the stalemate through an attack across Severnaya Bay near Sevastopol. Although Soviet commanders were aware of the potential for German amphibious operations, they did not anticipate an attack on Sevastopol itself, but rather a less risky attempt to circumvent the harbor defenses around Balaklava. This assumption was reinforced when Mimbelli’s MAS boats launched a series of feints off Cape Fiolent near Balaklava during the night of June 27-28.

In contrast, the southern shore of Severnaya Bay was guarded only by the exhausted survivors of the battered Soviet naval infantry units (fewer than 800 men in total), who believed they occupied a quiet sector. On the night of June 28–29, German sappers laid a smokescreen on the north side of the bay to conceal the launch of 130 assault boats of the 902nd and 905th Assault Boat Commandos, each capable of transporting a battalion across the bay. German aircraft made several attacks on the defenses around Inkerman to distract the Russians as the first wave of nearly 400 soldiers began the 20-minute crossing.

The defenders were thinly spread along the coast and failed to notice the landings. A single outpost overlooking the landing area was eliminated before the alarm could be raised. Incredibly, over 700 German soldiers had already landed before the Russians reacted. Soviet artillery fire damaged a quarter of the assault boats, but the Germans lost only two boats and suffered 33 casualties. In a major coup, the German assault troops managed to capture Sevastopol’s main power plant, cutting off the city’s electricity supply.

The psychological impact of the landing ended the stalemate and enabled the German XXX Corps and the Romanian Mountain Infantry to capture the crucial Sapun Heights southeast of Sevastopol and take over 4,700 prisoners. Stalin authorized the evacuation of the port on June 30, giving priority to senior officers. They spread panic as they abandoned their units to fight for places on the last transport planes and submarines to leave the city. Perhaps 200 commanders and NKVD officers escaped, although total Soviet losses may well have been 20,000 killed and 90,000 taken prisoner. Axis losses were nearly 36,000, but heavy damage was inflicted on both the Red Army and the Black Sea Fleet. The Luftwaffe alone reported destroying 611 motor vehicles, 123 aircraft, and 48 Soviet artillery batteries. German air raids sank 10,800 tons of Soviet shipping, including four destroyers, one submarine, three mountain bikes, six coastal vessels, and four freighters.

After eight months, the siege of Sevastopol finally ended with a German victory. But the relief was short-lived. Both sides faced the torture of Stalingrad.