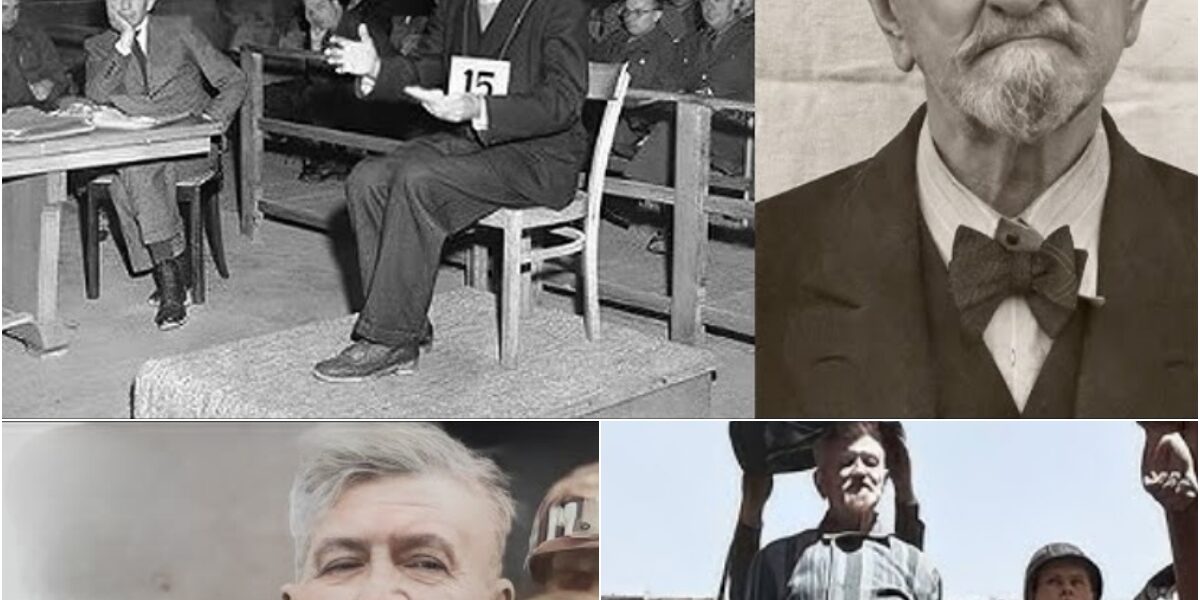

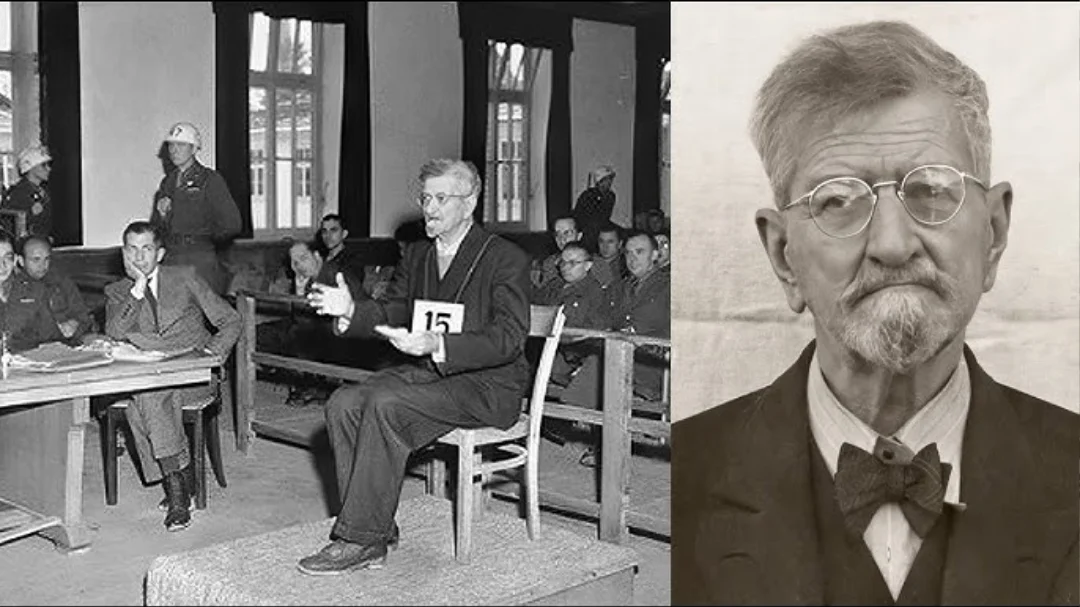

FROM MURDERER TO COWARD: The 74-Year-Old Nazi Doctor Who Killed 1,000 People at Dachau Wept and Begged for Forgiveness Before Execution

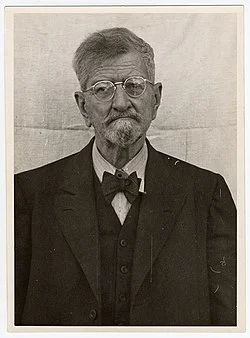

In the annals of World War II atrocities, the name Claus Schilling stands out as a chilling reminder of how science can be twisted into a tool of horror. Born on July 5, 1871, in Munich, Schilling was a renowned malaria researcher whose career took a sinister turn under the Nazi regime. Assigned to conduct experiments at Dachau concentration camp, Schilling’s work led to unimaginable suffering for countless prisoners, including Polish and German clergymen. His story, from a respected scientist to a war criminal responsible for brutal human experiments, is a haunting chapter of the Holocaust. This analysis, crafted for history enthusiasts and social media readers on platforms like Facebook, explores Schilling’s life, his inhumane experiments, and the devastating impact on his victims, urging us to confront the ethical boundaries of science in times of tyranny.

A Scientist’s Early Life and the Rise of the Nazis

Claus Schilling was born in Munich, then part of the German Empire, in 1871. A respected researcher, he dedicated much of his career to studying malaria, a disease that plagued many parts of the world. By 1936, his expertise led him to Italy at the request of Italian authorities, where he continued his work on tropical diseases. However, the global landscape was shifting dramatically. On January 30, 1933, Adolf Hitler was appointed Chancellor of Germany, ushering in a regime that would soon weaponize science for its genocidal agenda. When World War II erupted on September 1, 1939, with Nazi Germany’s invasion of Poland, the stage was set for Schilling’s descent into infamy.

In November 1941, Schilling’s fate intertwined with the Nazi machine. In Rome, he met Leonardo Conti, the German “Reich Health Leader,” who, under orders from SS chief Heinrich Himmler, assigned Schilling to conduct malaria experiments at Dachau concentration camp. Established in March 1933, Dachau was one of the first Nazi concentration camps, initially built to detain political prisoners but later used for horrific medical experiments. Schilling, already over 70 years old, accepted the assignment, stepping into a role that would forever tarnish his legacy.

The Horrors of Dachau’s Medical Experiments

Beginning in 1942, Dachau became a testing ground for Nazi medical experiments, with German physicians and scientists exploiting prisoners for research deemed critical to the war effort. Scientists from the Luftwaffe and the German Experimental Institute for Aviation conducted high-altitude and hypothermia experiments to aid pilots downed in icy waters, as well as tests to make seawater potable. Others, like Schilling, focused on pharmaceutical trials for diseases such as tuberculosis and malaria. These experiments, far from advancing human welfare, were marked by cruelty and disregard for human life, resulting in the deaths or permanent harm of hundreds of prisoners.

Schilling’s malaria experiments, which began in February 1942, were particularly brutal. Despite his claims that the research could be conducted harmlessly, the reality was far grimmer. Prisoners at Dachau were subjected to inhumane procedures, including having their hands and arms confined in cages filled with malaria-infected mosquitoes. After being deliberately infected, they were treated with synthetic drugs in doses ranging from high to lethal, often with devastating consequences. The victims, stripped of their dignity and agency, suffered excruciating pain and, in many cases, death. Among the earliest victims were Polish clergymen, targeted for their cultural and religious significance, though German priests, such as The Reverend Theodore Koch, were later subjected to the same horrors.

The Victims and Their Suffering

The prisoners chosen for Schilling’s experiments were not just numbers but individuals with lives, beliefs, and families. Polish clergymen, often seen as symbols of resistance against Nazi oppression, were among the first to endure the malaria trials. The inclusion of German priests like Theodore Koch further illustrates the indiscriminate cruelty of the experiments, as even those who shared the nationality of their captors were not spared. The method of exposure—caging limbs with infected mosquitoes—was not only physically agonizing but also psychologically dehumanizing, reducing prisoners to mere test subjects in Schilling’s quest for a malaria cure.

The use of synthetic drugs in varying doses added another layer of horror. High doses often led to severe side effects, while lethal doses claimed lives outright. The prisoners, already weakened by starvation and the brutal conditions of Dachau, had little chance of surviving such treatments. Schilling’s experiments, conducted under the guise of scientific progress, were a grotesque betrayal of medical ethics, prioritizing Nazi objectives over human lives. The suffering of men like Theodore Koch and countless others remains a stark testament to the moral bankruptcy of those who justified such atrocities in the name of science.

The Legacy of a War Criminal

As the war drew to a close, the Allies liberated Dachau in April 1945, exposing the full extent of the camp’s horrors. Claus Schilling was arrested and put on trial for his role in the medical experiments. Despite his defense that his research was intended to benefit humanity, the overwhelming evidence of prisoner suffering led to his conviction. Schilling was sentenced to death and executed by hanging on May 28, 1946, at the age of 74. His death marked the end of a career that had descended from respected science to complicity in Nazi crimes.

Schilling’s story raises profound questions about the ethics of scientific research under oppressive regimes. His willingness to conduct experiments on unwilling prisoners highlights the dangers of unchecked power and the perversion of knowledge for destructive ends. For history fans and social media audiences, Schilling’s tale is a gripping reminder of the human cost of the Holocaust and the need to safeguard ethical standards in science.

Claus Schilling’s journey from a celebrated malaria researcher to a war criminal at Dachau is a chilling cautionary tale. His experiments, which caused untold suffering for prisoners like Polish and German clergymen, reveal the depths to which science can fall when co-opted by tyranny. The stories of victims like The Reverend Theodore Koch remind us of the individual lives destroyed by Schilling’s actions. Schilling’s legacy is a warning: science, when divorced from humanity, becomes a tool of horror. Let the memory of his victims inspire us to uphold compassion and ethics, ensuring that such atrocities are never repeated.