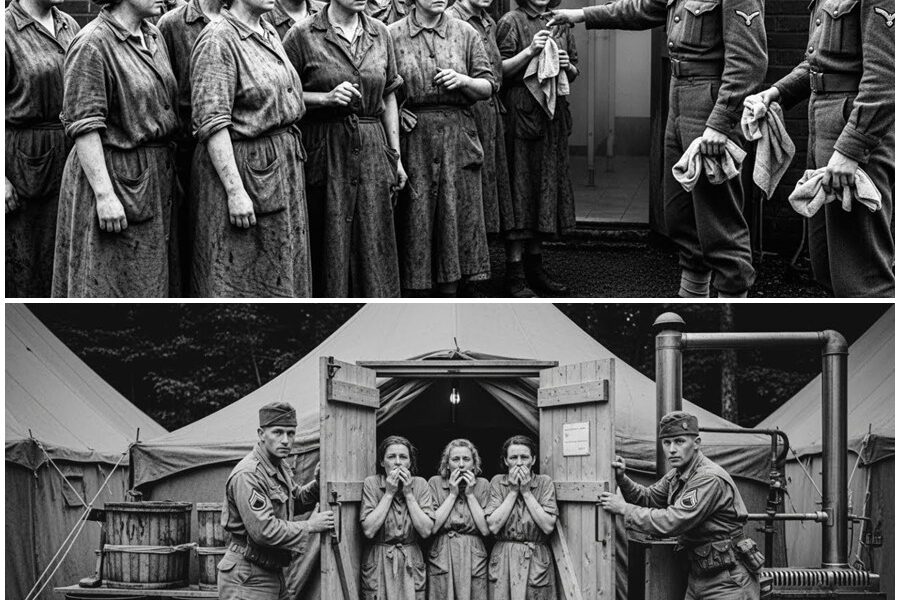

German Female POWs Hadn’t Bathed in 6 Months – British Built Private Bathhouses With Water and Soap

March 12th, 1945. Fort Ogulthorp, Georgia. The transport train hissed to a stop in the humid morning air. Greta Miller stepped onto American soil with trembling legs. 6 months without a proper bath. 6 months of filth crusted into her skin like a second uniform. Her Vermached auxiliary jacket hung loose on a frame that had forgotten what fullness felt like.

The smell of soap drifted through the Georgia pines. Real soap, not the costic lie that burns skin in the camps. She inhaled and felt something crack inside her chest.

847 German women stood on that platform. Radio operators, nurses, signals cores, veterans. All of them had been told the same lie. Americans would parade them naked through streets, mock their bodies, strip away every lasted shred of dignity.

Instead, a female American nurse approached with a clipboard. Her boots were polished. Her uniform was pressed. She smiled, not cruy, but with the tired professionalism of someone who had processed thousands of refugees. The nurse gestured toward a white wooden building. Steam rose from vents along its roof.

Greta looked at Anna Schrader beside her, a search light operator from Berlin, whose hands never stopped shaking. Neither woman spoke. They both understood. This was not what they had been promised. And in that moment, standing in the Georgia heat with soaps scented air filling their lungs, they realized everything they had been told was a lie.

The war had taught them that enemies were monsters, that capture meant death or worse, that mercy was weakness and kindness was a trap. Vermach training for female auxiliaries included specific warnings about American captivity. The lectures were clear. Americans treated German women as propaganda tools. They would photograph humiliation.

They would create spectacles of degradation. They would turn prisoners into exhibits of Aryan defeat. Greta had served 18 months in the women’s signals cores near Hamburg. She had watched her city burn under Allied bombing. She had pulled bodies from rubble with her own hands. She had learned to eat potato peels and call it soup.

By February 1945, Germany was collapsing. Supply lines shattered. Communication networks failed. Units dissolved into chaos as the Reich’s infrastructure imploded around them. When British forces captured Grea’s unit outside Bremen, she expected execution. Instead, she received a blanket and processed paperwork.

The British transferred hundreds of German women posed to American custody. They traveled by ship across an Atlantic that had swallowed so many before them. During the crossing, the women whispered stories. One claimed Americans forced prisoners to dance for entertainment. Another swore they used dogs to terrorize captives.

A third insisted American guards would separate the young from the old, keeping the former for brothel. None of them imagined hot water and soap. The Geneva Convention of 1929 established rules for prisoner treatment. Food, shelter, medical care, and hygiene were mandatory. On paper, these protections existed.

In practice, compliance depended entirely on the captor’s resources and willingness. By 1945, Germany held millions of Soviet prisoners in conditions that violated every convention article. Starvation, exposure, and forced labor killed them by the hundreds of thousands. The German government justified this by declaring Soviets subhuman, unworthy of protection.

Now those same German soldiers and auxiliaries stood on the receiving end, and they discovered something that shattered their worldview more effectively than any bomb. The Americans followed the rules, not because Germans deserved it, but because the rules existed. Greta clutched her small suitcase as guards led them toward processing.

Inside three photographs, a water stained diary, a rosary, everything she owned in the world. The Georgia morning was thick and heavy. Nothing like the frozen German winter she had survived. Pine trees surrounded the camp, their scent mixing with fresh paint and frying bacon. Real bacon, not meat made from God knew what. Her stomach cramped at the smell.

She had not eaten real meat in 8 months. The processing building was clean, spotless even. American nurses moved through stations with efficiency, checking names against lists, asking questions through translators. No one shouted. No one struck anyone. The violence she expected simply did not materialize. A translatter approached, a middle-aged German American with kind eyes.

He explained in careful hop deutsch that they would receive medical examinations, delousing and clean clothing, all according to Geneva Convention standards. Geneva Convention. The words felt foreign in her mouth. Distant, theoretical. She had never expected to benefit from them. The medical examination came first.

Behind canvas screens, an American doctor waited. She was a woman, which startled Greta more than anything else. Female doctors were rare in Germany, especially in military contexts. The doctor’s hands were gentle as she checked Grea’s heart, lungs, throat. She made notes without judgment. She asked about injuries and illnesses through the transl.

Then she handed Granta a clean towel and pointed toward another door. The delousing and bathing facility, the translator explained. Everyone must be clean before Bareric’s assignment. Belowing. The word stopped Grid’s heart. She knew about camps in the east. Whispers of shower rooms that were not showers at all.

Gas instead of water. Death instead of cleaning. Her breathing accelerated. Her vision tunnneled. This was it. This was where the Americans would reveal their true nature. Anna grabbed her arm. They walked together down a corridor toward the sound of running water. Other women followed in silence, each one bracing for horror.

They entered a large room with white tile walls and wooden benches. Individual shower stalls lined at the walls, each with a curtain for privacy. On every bench sat a small basket, soap, towel, clean clothing. Greta stared at the soap, white, rectangular, smelling faintly of lavender. Not harsh lie, not military issue, real soap, the kind her mother used to buy before the war.

A female American soldier stood at the entrance. She gestured toward the showers and spoke in English. The translator’s voice echoed across the tile. 20 minutes. The water is hot. There are private stalls. Clean yourselves thoroughly. Leave old clothes in bins. New clothes provided. No one moved.

The women looked at each other, searching for the trap. 30 seconds passed. 40. The silence stretched like wire. Then Anna stepped forward, grabbed soap, and walked to a stall. The sound of water starting broke the spell. Greta moved next. Her hands shook as she picked up the soap. It was heavy, solid, real. She entered a stall and closed the curtain. Privacy.

They were giving her privacy. She stood under the shower head for 10 seconds, unable to process what was happening. Then she turned the handle. Hot water poured over her head. Actually, hot, not lukewarm. not cold with occasional warm trickles, genuinely hot water that steamed in the cool air and ran through six months of accumulated filth. Greta gasped.

Tears mixed with water and soap as she began scrubbing her matted hair, her gray skin, her cracked hands. The soap foamed easily, cleaning without burning. She washed and washed, watching brown water swirl down the drain, carrying away more than just dirt. Around her, she heard other women crying.

Some laughed in disbelief. Anna’s voice cut through the sound, sharp and angry, as if furious that the enemy could provide something so basic, so human. The 20 minutes ended too soon. Greta emerged feeling lighter, cleaner, more alive than she had in half a year. Her skin was pink. Her hair, though still tangled, felt soft again.

She dried herself and dressed in the clean clothes. Gray work pants, white shirt, new underwear, socks without holes. The clothes fit well enough, mass- prodduced, but intact, whole, warm. When all the women had finished, guards led them toward the messole. They walked in stunned silence, each one trying to reconcile expectation with reality.

They had been promised degradation. They had received dignity. The mess hall smelled like breakfast, not watery gr, not sawdust bread, actual breakfast, the kind Greta remembered from childhood Sundays before everything changed. She picked up a metal tray and moved through the serving line. An older black cook with massive forearms spooned food onto her tray without comment.

Scrambled eggs, bacon, toast with butter, coffee, a small bowl of oatmeal. An orange. Greta stared at the tray. This was more food than she had seen in a single meal in 2 years. more food than her family in Hamburg had probably eaten in a week. She looked up at the cook, searching for mockery for cruelty.

He just nodded toward the tables. “Go on, miss. Find a seat.” She sat with Anna and a dozen others. They all held their trays with the same disbelief. The eggs steamed. The bacon glistened. The coffee smelled rich and dark. No one ate. They just stared at food that seemed impossible. A young woman from Munich finally picked up her fork with trembling hands.

She took a bite of eggs. Her eyes widened. She took another bite. Then she began crying, tears rolling down her clean cheeks as she chewed. That broke the spell. Greta tasted the eggs fluffy, seasoned perfectly. She bit into bacon and flavor exploded across her tongue. She ate the toast, butter melting across her teeth. Around her, women ate in silence, tears streaming down their faces.

Anna ate mechanically, her face hard. But Greta saw her hands shaking as she brought the fork to her mouth. “This is wrong,” Anna whispered. “They shouldn’t feed us like this.” “Why?” Greta asked. “Why is it wrong?” “Because they’re the enemy.” Because we fought them. Because our brothers died fighting them.

Because Anna stopped. Because it made everything they had been told a lie. An American guard walked past their table, a young woman barely older than Greta. She glanced at their empty coffee cups and gestured toward an urn at the room’s end. More coffee over there if you want it. Help yourself.

Help yourself. as if they were guests, as if they had not been enemies weeks ago, as if they deserved comfort and courtesy and hot coffee whenever they wanted it. Greta peeled her orange slowly. The citrus smell was overwhelming after months without fresh fruit. It was sweet and cold and perfect. She ate it section by section, making it last.

When she finished, she felt something she had not felt in months. Full. actually genuinely full, but the fullness in her stomach could not fill the emptiness of confusion in her mind. The barracks were simple wooden structures with screened windows and solid roofs. Inside, rows of bunk beds lined the walls.

Each bed made up with sheets, blanket, pillow, not straw pallets shared by three women. Real beds. Greta was assigned a lower bunk near a window. She sat on the mattress and pressed her hand against it, firm, but not hard. Actual padding, not just canvas over boards. She lay back slowly and stared at the wooden ceiling.

At the foot of each bed was a small locker. Guards explained that personal items could be stored there. Letters, photographs, books. They would not be confiscated unless security required it. Greta placed her suitcase inside and tucked her diary under her pillow. A potbelly stove sat in the barrack center, already stacked with wood for cold nights, the translatter explained.

Someone will show you how to operate it. Extra blankets available if needed. It was March in Georgia. Nights were cool, not cold. Yet the Americans planned for the possibility that German prisoners might be uncomfortable. They provided heating. They provided extra blankets. That evening, after lights dimmed, the women whispered in their bunks.

Some discussed families left behind in Germany’s ruins. Others talked about the uncertain future, but most discussed the bath and the food. Hot water, someone whispered in darkness. They gave us hot water and soap. Real soap. The bacon was real. I could taste it. Greta said nothing. She lay with her hand pressed against her clean skin.

Feeling the softness the soap head created. She pulled out her diary and wrote by moonlight filtering through the window. March 12th, 1945. We have arrived in America. I do not understand this place. The enemy treats us better than our own country did. I am clean. I am fed. I have a bed. I should feel relief.

But all I feel is confusion and shame. What kind of enemy shows kindness? She closed the diary and tucked it away. Outside cricket sang in the Georgia night. The sound was peaceful, normal, so unlike the air raid sirens that had been the soundtrack of her life for years. She fell asleep to that sound. Clean, fed, and more confused than she had ever been.

Days settled into routine. Each morning at 6, a bell woke them. Not harsh alarms, just a simple bell. They dressed and walked to the messole. Oatmeal, toast, sometimes eggs. Always coffee, then work assignments, laundry duty, kitchen work, light maintenance. None of it was hard. They were paid in camp script, internal currency for the canteen.

The canteen shocked them most. It stocked chocolate bars, cigarettes, toothpaste, cones, writing paper, luxuries that seemed impossible. Greta saved her script for a week and bought a Hershey bar. She held it for minutes before unwrapping it, staring at the brown paper and silver foil.

When she finally bit into it, the chocolate was sweet and creamy. She ate it slowly and cried because it reminded her of childhood Christmases before everything burned. Meals continued generous. Lunch brought sandwiches or soup with bread. Dinner included meat, potatoes, vegetables, sometimes dessert. The women began noticing changes in their bodies.

healthier skin, shinier hair, energy they had not felt in years. They looked in mirrors and barely recognized themselves. They looked alive again, but every improvement carried a cost because every bit of health they gained reminded them of what they had left behind. The letters started arriving in late March. Red Cross had established contact between Po and families. Many letters never arrived.

Some took months, but when they came, they carried news that broke hearts more effectively than any cruelty. Greet’s first letter arrived on a Tuesday. She recognized her mother’s handwriting. Her hands shook as she opened it. The letter was short, written in pencil on torn notebook paper. Hamburg was gone.

Their neighborhood was rubble. The family lived in a cellar. Her father searched for work that did not exist. They ate soup made from potato peels. Her brother had not been heard from since February. The British gave ration cards, but rations were tiny. If you can, the letter ended, “Please send anything. Even a little food would help.

We are so hungry.” Greta read it three times and carefully folded it under her pillow. That evening, she could not eat dinner. She sat staring at her tray of pot roast, mashed potatoes, green beans, and bread, physically sick. Her family was eating potato peel soup. She was eating pot roast.

Gita’s name appeared on the first repatriation list in September. The final days in the American camp passed quietly. women packing small bundles, thanking guards and halting English, memorizing every detail they knew they’d miss. On her last morning, Greta stood under the hot shower one last time, letting the water wash over her as she cried.

Leaving felt like stepping out of sanctuary. The journey home was long, ship, train, processing centers, each step fair, but stripped of the strange gentleness she had known in Georgia. When she reached Hamburg in late October, she scarcely recognized it. Whole streets were gone, the air thick with smoke and grief.

Her family lived in a cellar. They embraced her with shaking hands. Her mother studied her face, stunned by her health. Greta felt guilt like a stone in her stomach. That night, they shared thin soup. Her father asked about the camp. She told him everything. When she finished, he looked down and said, “They were better to you than we were to ourselves.

Life went on. Germany rebuilt.” Greta married, raised children, but the memory of hot water and soap never faded. When her daughter later asked why the Americans had been kind, Greta struggled for words. “Because they believed even enemies are human,” she said at last. “Cruelty would have been easier for me to understand.

kindness made me question everything. She kept her diary for decades, its pages filled with the confusion and clarity of those months. Years later, she wrote, “The enemy gave me food, water, dignity. I arrived expecting hatred and found humanity instead. That mercy broke me and remade me.” To her grandchildren, she would say, “The Americans taught us that the measure of a nation is not how it treats its friends, but how it treats its enemies.

” And that she believed was the story worth remembering.