German POWs Thought Canadian Winter Would Kill Them — Until Locals Showed Them How to Survive It

December 1940, German prisoners of war arrived in Canada, convinced the brutal winter would kill them. Temperatures plunging to 40on grittywigs, winds that could freeze exposed skin in minutes. A frozen wasteland they’d been told was impossible to survive.

But instead of watching them freeze to death, Canadian guards and local farmers did something that would shatter everything these men believed about strength, survival, and which side was truly civilized. What could enemy civilians possibly teach battleh hardened vermached soldiers that would make thousands of them abandon their homeland after the war and return to the country that once imprisoned them? Europe was burning.

Germany’s war machine had crushed every country in its path for 18 straight months. Poland fell in weeks. Norway, Denmark, the Netherlands, Belgium, and France all collapsed under the weight of panzer divisions and dive bombers. The Nazi swastika flew from the frozen coast of Norway down to the sunny beaches of France.

Adolf Hitler stood as master of continental Europe, controlling everything from the Arctic Circle down to the border with Spain. Only Britain remained, and every night, German bombs rained down on London, trying to break the last free nation in Western Europe. Across the Atlantic Ocean, Canada watched and prepared. This nation of just 11 and a half million people had already made a choice that would change everything.

Over 200,000 Canadian soldiers had crossed the ocean to fight. Factories that once made tractors now built tanks. Shipyards worked day and night building corvettes to hunt German submarines. Every able man between 18 and 40 was either overseas training to go overseas or working in a war factory. Canada had committed its entire future to stopping Hitler.

But now Canada faced a new problem, one nobody had really planned for. German prisoners were arriving by the shipload. Hundreds at first, then thousands. These were the men pulled from sinking Yubot in the freezing North Atlantic. Their submarines sent to the bottom by Canadian corvettes and British destroyers. They were Luvafa pilots shot down over England during the Battle of Britain.

men who had parachuted into British fields and were now being shipped across the ocean. They were sailors from German surface raiders, warships that had been hunting Allied convoys until the Royal Navy caught them. The first prison ships steamed into Halifax Harbor in late autumn. Guards marched the prisoners off the ships and loaded them onto trains.

These trains would carry them deep into the Canadian interior to places with names the Germans couldn’t pronounce. Camp 30 near Bowmanville in Ontario. Camp 133 at Lethbridge in Alberta. Camps in Quebec in New Brunswick scattered across a country so vast that Germany could fit inside it three times over.

The German prisoners stared out the train windows as the landscape rolled past. They saw forests that stretched to the horizon. They saw farms bigger than entire German villages. They saw small towns with electric street lights, paved roads, and more automobiles than they’d seen in any German city.

And they felt the temperature dropping with each mile north and west. These men had been told things about Canada. Their officers had briefed them. The Nazi Propaganda Ministry had published reports. Canada was a frozen wasteland, they said. A primitive colonial backfield where people lived like pioneers. The winters killed anyone unprepared.

Temperatures dropped so low that exposed skin froze solid in minutes. Winds howled across empty planes with nothing to stop them. Men caught outside in a Canadian winter storm simply died, frozen into statues of ice. The prisoners believed these stories because they had no reason not to. None of them had ever been to Canada. Few had even met a Canadian.

They knew cold winters from Germany, sure, but this was supposed to be different. This was supposed to be cold that killed. When they arrived at the camps, the Germans saw wooden barracks surrounded by wire fences. Guard towers stood at each corner. Search lights swept the grounds at night. The camps looked temporary, thrown together quickly, not like the solid concrete and stone buildings Germans built to last. The barracks were just wooden walls and tar paper roofs.

How could these flimsy buildings protect anyone from the killing cold they’d been warned about? November turned to December. The temperature dropped. Then it dropped more. By early January 1941, the thermometers read 30° below 0. That’s 22° below 0 F. But the wind made it feel even colder.

Wind chill drove the real temperature down to 40 below zero or worse. The prisoners had never felt anything like it. They watched through the windows as Canadian guards walked around outside like it was nothing. The guards wore heavy coats, sure, and thick gloves and wool hats, but they moved normally. They talked and laughed.

They didn’t act like men in mortal danger. The Germans didn’t understand how this was possible. Inside the barracks, the prisoners huddled together. Many still wore their modified German uniforms, wool coats that had been fine for a European winter, but felt like paper against this Canadian cold. They piled every blanket they had on their bunks.

They stayed inside as much as possible, moving only when absolutely necessary. They waited for men to start dying. The German officers held meetings. They discussed rationing movement to conserve body heat. They talked about which men were weakest and might die first. They prepared reports to send back to Germany about the harsh conditions if any of them survived to send such reports.

Some men wrote letters home that might be their last, describing the brutal cold and saying goodbye to families they didn’t expect to see again. At night the wind screamed across the prairie and through the Ontario hills. It found every crack in the wooden walls. It rattled the windows.

The sound alone was terrifying, like something alive and hungry prowling around the buildings, looking for a way in. The prisoners lay in their bunks and wondered if they would wake up in the morning or if the cold would take them in their sleep. This was how it was supposed to end for them. Not in battle, not in some heroic last stand, but frozen to death in a prisoner camp on the other side of the world.

The cold would do what British bullets and depth charges had failed to do. They would become statistics. Numbers in a report about winter casualties. But morning came and all the prisoners were still alive. What happened next would change everything they thought they knew about survival, about their enemies, and about what real strength actually meant. The prisoners were alive.

But they still expected death to come, just not today. Maybe tomorrow or the next day when the temperature dropped even lower or when a real blizzard hit. The German prisoners rationed their movements and prepared for the inevitable. Then something strange started happening. Something none of them had prepared for.

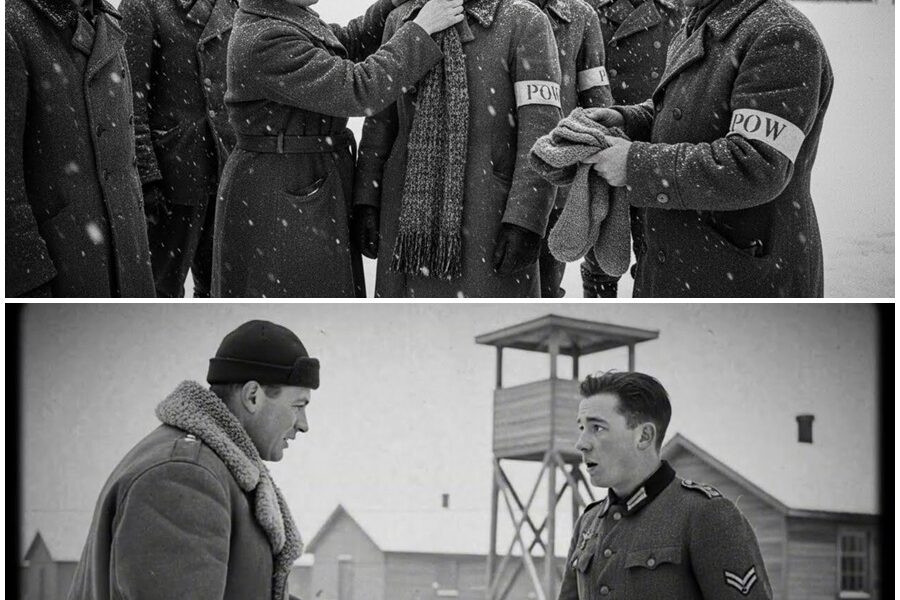

The Canadians, the very people who were supposed to be guarding them, started teaching them how to survive. Canadian guards began arriving at the barracks with boxes, big wooden crates and cardboard boxes filled with clothing. They opened the boxes and started handing things out. Wool socks, thick and heavy, three pairs for each man. furlined mittens that came up past the wrist. Knitted scarves in different colors clearly made by hand.

Heavy coats called machin lined with wool and built to keep a man warm even in the worst weather. Woolen hats that Canadians called toques, pronounced like 2k that pulled down over the ears and could be rolled up or down depending on how cold it was. A farmer’s wife from a nearby town arrived one morning with her teenage daughter.

She’d heard the prisoners didn’t know how to dress for Canadian winters. She went from barracks to barracks, showing the men how to wrap their scarves properly, tucking the ends inside their coats to seal in heat. She demonstrated how to stomp snow off boots before entering a warm building. Because melted snow meant wet feet and wet feet meant frostbite.

Her daughter showed them how to pull their wool socks up over their pant legs to keep snow from getting inside. These were small things, everyday things that every Canadian child learned. But to the Germans, they were survival secrets that could mean the difference between keeping all their toes or losing them to the cold.

But the guards didn’t just hand out the clothing and leave. They stayed and showed the prisoners exactly how to use it to stay alive. Layer your clothing, they explained. Don’t wear one thick layer. Wear several thinner layers with air trapped between them. The air acts like insulation. Keep moving to generate body heat.

But don’t sweat because wet clothing will freeze. Protect your hands, your feet, your ears, and your nose first because those freeze fastest. Never touch metal with your bare skin in this cold because your skin will stick to it and tear off when you pull away. If you see white patches on someone’s face, tell them immediately because that’s frostbite starting.

The Germans listened and learned. They had no choice. These Canadians understood this winter in a way the prisoners never could. The guards weren’t just keeping them alive out of duty. They were actively teaching them survival skills, sharing knowledge that Canadians learned as children growing up in this climate.

Enemy soldiers learning from their capttors how not to die. Then came the food. The camp kitchen served breakfast at 7 in the morning. The prisoners lined up with their metal trays, expecting watery soup and stale bread, the kind of rations they’d heard about in other prison camps. Instead, they got bowls of hot porridge with brown sugar already mixed in.

Four strips of bacon, crispy and still hot. Fresh bread, actual fresh bread baked that morning with real butter. coffee with milk. Not the fake coffee made from acorns that Germans had been drinking for years, but real coffee with real milk.

One Yubot officer, who’d been pulled from the Atlantic when his submarine was sunk, couldn’t believe what he was eating. He wrote in his diary that night that he was eating better than officers stationed in Berlin. He counted 2800 calories per day. 2800. In Germany, civilians were living on ration cards that gave them barely enough to survive. Here, as prisoners, they ate like kings. Lunch brought beef stew with carrots and potatoes.

Chunks of real beef that hadn’t been stretched with filler or substitutes. Dinner meant roast pork or chicken or more beef, always with vegetables. Fresh vegetables, even in the middle of winter, pulled from root sellers where Canadians stored their harvest. Desserts came with dinner. Apple pie, bread, pudding with raisins, sometimes cookies.

The prisoners couldn’t understand where all this food came from, or why their capttors fed them so well. The guards shared their thermoses of hot coffee during work details outside. They’d pour cups for the prisoners and stand around talking like they were all just workers on a break, not enemies separated by a war.

When prisoners expressed surprise at the treatment, the guards laughed. “This is just how things are done here,” they’d say. Geneva Convention and all that, but it seemed like more than just following rules. It seemed like the Canadians actually cared whether the prisoners were comfortable. The technology shocked the Germans even more than the food.

The barracks had central heating systems, actual furnaces in basement that burned coal or oil, and sent hot water through pipes in the walls. The thermostats kept the buildings at 18° C, which is 64° F, even when it was 35 below zero outside. Hot water came from taps. Turn a handle and hot water flowed out as much as you wanted. Electric lights worked all the time, never flickering or going out like they did in German cities where power was rationed.

The camp at Medicine Hat in Alberta got fresh milk delivered every morning by refrigerated truck. Refrigerated trucks in winter. The prisoners learned that Canada had so much refrigeration infrastructure that the trucks ran year round, keeping things cold in summer and preventing them from freezing solid in winter. Germany barely had enough trucks to move military supplies.

And here, Canada had specialized refrigerated trucks delivering milk to prison camps. Local farmers started hiring prisoner work gangs for the sugarbeat harvest. The prisoners rode in trucks out to the farms and spent days pulling beats from the frozen ground. The work was hard, but the farmers paid them 25 cents per day in camp script.

Money they could spend at the camp store for cigarettes, chocolate, and other items. In European camps, prisoners worked for nothing. Here they earned wages. Working on the farms opened the prisoner’s eyes even more. They saw machinery they’d only heard about in propaganda films that claimed to show American industrial might.

One farmer in southern Alberta owned three tractors for a 640 acre farm, three tractors. In Germany, entire villages shared one tractor if they were lucky. These Canadian farmers had combines, mechanical cedars, and harvesting equipment that did the work of 50 men. The barns were bigger than most German houses.

The silos held more grain than a German village produced in a year. The camp commanders arranged for prisoners to attend hockey games in nearby towns. They were allowed to ice skate on camp ponds when the water froze smooth. Canadian guards continued the lessons, showing them how to play hockey, how to skate backward, how to stop by digging in the edges of the blades, how to handle the puck with the stick. The prisoners learned something important from this.

Canadians didn’t just survive the winter, they lived in it. They had built an entire sport around ice and cold. They had parties and festivals in the middle of winter. Children played outside in weather that would have kept German children locked indoors. The winter wasn’t killing them. It wasn’t even trying.

The Canadians had tamed it somehow, turned it from an enemy into just another part of life, something to work with instead of fight against. And slowly, as the prisoners learned these lessons about survival, something deeper started shifting inside them. The change came slowly at first, like ice melting at the edges of a frozen lake. The German prisoners started asking questions they’d never thought to ask before.

If Canada could feed its prisoners better than Germany fed its officers, what did that say about German strength? If Canadian farmers owned more machinery than German factories could produce, what did that say about German industrial power? If ordinary Canadian families donated warm clothing to enemy soldiers, what did that say about German propaganda claiming that non-Germanic peoples were inferior and weak? Christmas 1941 brought everything into sharp focus. The prisoners woke that morning expecting nothing special.

Christmas in a prison camp should be just another day, maybe slightly worse because it reminded them of home and family. Instead, the camp commanders announced a special Christmas dinner following the Geneva Convention traditions for treatment of prisoners. The dining hall smelled like a feast.

The kitchen staff had been cooking since before dawn. They brought out roast turkeys, golden brown and stuffed with bread stuffing that had sage and onions mixed in. Mashed potatoes came in huge bowls with pools of melted butter on top and rich brown gravy in serving boats. Cranberry sauce, bright red and sweet tart, sat in dishes on every table.

Fresh rolls, still warm from the oven, came with more butter. Three different types of pie followed the main course. Apple pie with cinnamon and sugar. Pumpkin pie with whipped cream. Mince meat pie that some prisoners had never even heard of before. Coffee flowed freely. Chocolate bars sat at every place setting. The prisoners sat at the tables in stunned silence at first.

Many had tears in their eyes. They hadn’t seen this much food since before the war started. Some hadn’t seen a feast like this ever in their entire lives. German families had been tightening their belts since 1939. Ration cards controlled everything. Butter was a luxury. Real coffee had disappeared.

Meat came once or twice a week if you were lucky. And here they sat, prisoners of war, enemy soldiers, eating better than any German family would eat that Christmas. But the food was just the beginning. Canadian families had sent Christmas packages to the camps. Boxes arrived by the dozens, each one addressed to the prisoners in general, not to anyone specific.

Inside were hand knitted socks with patterns of snowflakes and reindeer, homemade cookies wrapped in wax paper, still fresh and sweet. Tins of tobacco for the men who smoked. playing cards, books, and letters. Letters from Canadian women and children, wishing the prisoners a merry Christmas and hoping they were well.

A prisoner named Ernst Bower sat in his barracks that night trying to write a letter home to his mother. The camp sensors would read it before it got mailed. He knew that, but he had to try to explain what was happening to him. He wrote slowly, choosing each word carefully. Mother, I don’t know how to explain this. He wrote, “We are prisoners, and yet we are treated like guests who have fallen on hard times.

The local church sent us himnels in German so we could sing Christmas carols in our own language. A farmer’s wife brought us stolen she baked herself, the same Christmas bread we used to have at home. I have not felt this kind of human warmth since before the war. What have we become in Germany that we forgot this is how civilized people behave? The letter troubled the camp sensor who read it, not because it revealed military secrets or contained anything dangerous, but because it revealed something shifting in the prisoner’s mind. The sensor filed the

letter in a folder of similar letters that were arriving more and more frequently. The prisoners were changing. The camp commanders started allowing educational programs. Camp 30 became almost like a university. Prisoners who had been professors or teachers before the war began organizing classes, engineering courses, philosophy, languages, mathematics, history.

The Canadian government provided 1,200 textbooks, shipping them to the camp at government expense. The prisoners could take correspondence courses with real Canadian universities and earn legitimate academic credits that would be recognized after the war. The classes became popular quickly. Men who’d spent years being told that strength and military power were all that mattered now sat learning about literature, art, and science. They read books that had been banned in Germany.

They discussed ideas that would have gotten them arrested back home. The Canadian guards didn’t care what they read or discussed as long as it wasn’t escape plans. But the deepest lessons came from the winter itself and how Canadians had taught them to survive it. The prisoners began to understand that cooperation and community knowledge were more powerful than any individual strength.

When a guard showed a prisoner how to bank snow against a building for extra insulation, he wasn’t just teaching a survival trick. He was showing that humans survive by sharing what they know, by helping each other, by building on the knowledge of everyone who came before. The locals, farmers, towns people, guards were teaching them that survival wasn’t about being the strongest or the hardest.

It was about working together. One prisoner had his awakening during a blizzard in February 1943. His name was Klaus Hermon, and he’d been a Hitler youth leader before joining the Luftvafa. He believed everything he’d been taught about German racial superiority and the weakness of other peoples. Then the blizzard hit, one of the worst storms of the winter.

Snow fell so thick you couldn’t see 10 ft ahead. Wind howled at 70 mph. The temperature dropped to 40 below zero with wind chill making it feel even colder. The guards couldn’t get from their quarters to the camp kitchen. The roads were buried under snow drifts taller than a man. The camp would miss breakfast and maybe lunch, too.

But then trucks appeared through the blinding snow. Local towns people had organized a convoy. They’d loaded their trucks with pots of hot soup and loaves of fresh bread. They drove through dangerous white out conditions, risking their lives to make sure enemy prisoners didn’t go hungry. Hermon stood at the barracks window, watching those trucks arrive.

He watched Canadian civilians climb out into the screaming wind and carry heavy pots of soup toward the dining hall. These people had no reason to risk their lives for German prisoners. The prisoners couldn’t do anything for them in return. Nobody would have blamed the Canadians for staying safe at home and letting the prisoners miss a few meals. But they came anyway.

That night, Herman wrote in his journal. I understood for the first time that strength is not proved by crushing the weak, he wrote. It is proved by protecting them when no one would blame you for abandoning them. Everything I was taught about power and superiority was a lie. The Canadians are not weak because they show kindness. They are strong enough that they can afford to be kind.

We Germans thought we were strong because we were hard and cruel. But real strength is what I saw today. Real strength is driving through a killing storm to feed your enemies. Other prisoners were having similar thoughts. They’d been taught that the German people were destined to rule because they were superior in every way.

But if that was true, why did Canadian farmers have better equipment than German factories could make? Why did ordinary Canadian families have more food than German officers? Why did this supposedly backward colonial country treat prisoners better than Germany treated its own citizens? The propaganda fell apart when measured against reality.

You couldn’t ignore the food on your plate, the warm coat on your back, the heated barracks keeping you alive, and the simple human kindness shown by people who had every reason to hate you. The prisoners began to see themselves differently, too. They weren’t the heroes they’d imagined.

They were young men who’d been lied to and used by a government that didn’t care if they lived or died. The Canadians showed them what a real civilization looked like. And it wasn’t built on conquest and racial theories. It was built on knowing how to live in a hard place and helping others learn to live there, too. The war eventually ended, as all wars do.

But for the German prisoners who’d learned to survive the Canadian winter, going home would prove harder than anything they’d endured in captivity. May 1946, the war had been over for a full year. Germany lay defeated, split down the middle between the Soviet Union on one side and America, Britain, and France on the other.

The third Reich that was supposed to last a thousand years had collapsed after just 12. Now the prison ships were running in reverse, carrying German prisoners back across the Atlantic to a homeland that no longer existed in any form they would recognize. Ernst Bower stood on the deck of a transport ship, watching the Canadian coast disappear behind him. In his duffel bag, he carried everything he owned in the world.

a heavy Canadian wool coat that had kept him warm through five winters. Two pairs of thick socks knitted by a woman in Bowmanville whose name he’d never learned. A book on modern agricultural techniques that the camp education officer had given him as a parting gift and a small wooden cross carved by a fellow prisoner during the long winters. That was everything.

His entire life fit in one canvas bag. The ship took two weeks to cross the Atlantic. Bower stood at the rail every day, watching the gray water roll past and thinking about what waited for him. Letters from the Red Cross had told him the basic facts. Hamburgg was destroyed. 70% of the city was rubble.

His family home no longer existed, just a pile of broken bricks and burnt wood where a house used to stand. His father had died in 1943, killed in the bombing. His mother had fled to Dresden to stay with relatives and died there when that city burned in February 1945. His younger brother was missing, probably dead somewhere on the Eastern Front.

There was nothing left of the life he’d known before the war. The ship docked at Hamburgg in early June. Bower walked down the gang plank carrying his duffel bag and stepped onto German soil for the first time in six years. The smell hit him first. Ash and decay and human waste. The city smelled like death. He walked through streets he’d known as a boy but couldn’t recognize now.

Every building was damaged or destroyed. Walls stood without roofs. Windows gaped empty. Rubble filled the spaces between broken buildings. People moved through the ruins like ghosts, thin and gray and silent. He saw children digging through garbage piles looking for anything edible. Old women pulling carts loaded with salvaged wood for cooking fires.

Men with missing limbs sitting on corners begging. These were his people, Germans, the master race that was supposed to rule the world. They looked like they were barely surviving. Bower found a refugee center where the Red Cross was helping returning prisoners. They gave him papers and ration cards.

The ration cards entitled him to,200 calories per day if the food was available. Sometimes it wasn’t. He thought about the 2800 calories he’d eaten every day in Canada and felt sick. He thought about the Christmas feast with turkey and three kinds of pie and wanted to cry. His own people were starving while he’d spent the war eating better than he ever had in his life.

The winter of 1946 and 1947 became known as the hunger winter. The hunger winter. It was the coldest winter in Germany in 50 years. Temperatures dropped below zero and stayed there for weeks. There was no coal for heating because the mines weren’t producing enough. There was no wood because people had already burned everything they could find.

The buildings had no glass in the windows, just boards or cardboard that did nothing to keep out the cold. Bower survived that winter only because of what Canadians had taught him. He found a group of families huddled in a partially destroyed apartment building. They were wearing everything they owned in single thick layers, shivering under thin blankets.

Bower showed them the Canadian way. “Take off those heavy coats,” he told them. “Layer thinner clothes with air between them.” The families looked at him like he was crazy, but they were desperate enough to try. Within an hour, they felt warmer than they had in weeks.

He taught neighbors to bank snow against the outside walls for insulation, the same technique a Canadian guard had shown him. He demonstrated how to recognize the white patches of frostbite on children’s faces and how to warm the skin safely. He shared his Canadian wool coat with an elderly woman who had nothing but newspapers wrapped around her shoulders. The coat saved her life.

But even with that knowledge, people died. Thousands died from cold and hunger that winter. The cities were full of frozen bodies that nobody had the strength to bury until spring. Bower survived, but he knew he was only alive because Canadians had cared enough to teach an enemy how not to freeze.

Klouse Herman, the former Hitler youth leader who’d watched Canadians risk their lives to bring soup through a blizzard, came home to find nothing. His entire family was gone. His city was rubble. He had no job, no home, no future he could see. He spent two years trying to rebuild a life in Germany. But everything felt wrong. The people were broken.

The economy was destroyed. The country was occupied by foreign soldiers. And everywhere he looked, he saw the lies he’d believed being proved false by reality. In 1948, Canada announced a new immigration program. Former German prisoners of war could apply to immigrate if they had skills Canada needed, and if their war records were clean.

No war crimes, no SS membership, no Nazi party leadership positions, just regular soldiers who’d been captured and imprisoned and wanted a new start. Herman applied immediately. So did Bower. So did thousands of others. They wanted to go back to the place where they’d been prisoners. They wanted to return to the country that had defeated them in war. That seemed crazy to other Germans who heard about it.

Why would you go back to your prison? But the former prisoners understood something others didn’t. Canada wasn’t their prison. It was the place where they’d learned what a real country looked like, what real strength meant, what real civilization was built on. Horse Leebeck was among them. The Yubot officer who’d once written about eating better in captivity than officers in Berlin now worked as a marine engineer in Halifax, the same port where he’d first arrived as a prisoner. He designed safety systems for fishing vessels using

his submarine experience to help Canadian fishermen survive the North Atlantic. When people asked why he’d come back, he’d simply say that Canada had taught him the difference between surviving and living. He chose to live. By 1953, approximately 6,000 former German prisoners of war had returned to Canada as immigrants. They brought wives and children.

They settled in the same towns where the camps had been. They became farmers in Saskatchewan and Alberta, working the same fields where they’d once worked as prisoners. They became engineers and teachers and shop owners. They joined the communities that had once guarded them. Ernst Bower bought a farm in Saskatchewan in 1954.

He used the agricultural techniques he’d learned from Canadian farmers and from the book the camp officer had given him. He married a German woman who’d also immigrated, and they had three children. He taught his children to skate on the frozen pond behind the farmhouse. He showed them how to dress in layers for the cold.

He checked on his neighbors during blizzards, just like Canadians had once checked on him. He built a life in the country that had once imprisoned him, and never regretted his choice. Klaus Herman became a teacher in Lethbridge, teaching at the same high school that was built near where Camp 133 had stood. He taught history and citizenship.

He told his students stories about the war, about what he’d believed and how wrong he’d been. He told them about the blizzard of February 1943 and the town’s people who’d risked their lives to bring soup to enemy prisoners. He wanted them to understand something important. Your country defeated us not just with weapons, Heramman told his classes, but by showing us there was a better way to be human. The greatest shock of the war wasn’t the winter or the cold.

It was learning that everything we’d been told about strength and superiority was a lie. Real strength is teaching your enemy how to survive when you could simply let them freeze. True power isn’t found in cruelty. It’s found in driving through a blizzard to feed people who can’t repay you. And genuine civilization means building a society in one of the harshest climates on Earth and then sharing that knowledge with anyone who needs it, even your enemies. The lesson survived in a simple truth that Herman and Bower and 6,000 others

carried with them for the rest of their lives. The cold didn’t kill them because Canadians refused to let it. Not out of weakness, but out of a deeper strength. The strength of a society that had mastered winter. Not through domination, but through cooperation. The strength of a people who understood that survival was a skill worth sharing with everyone, even enemies.

Because that’s what civilized people do. In the end, the German prisoners learned to survive the Canadian winter. But more importantly, they learned why survival alone was never the point. What mattered was how you survived and who you helped survive alongside you. That was the lesson they carried back to Canada when they returned as free men. That was the lesson they taught their children and grandchildren.

That was the lesson that turned enemies into neighbors and prisoners into citizens. The winter taught them how to survive.