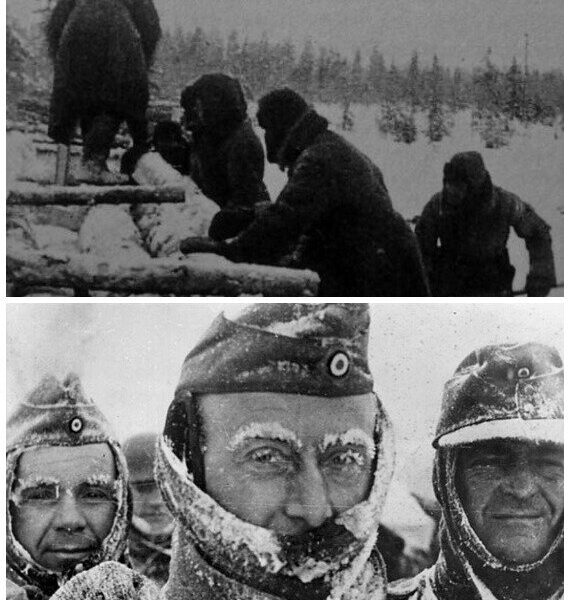

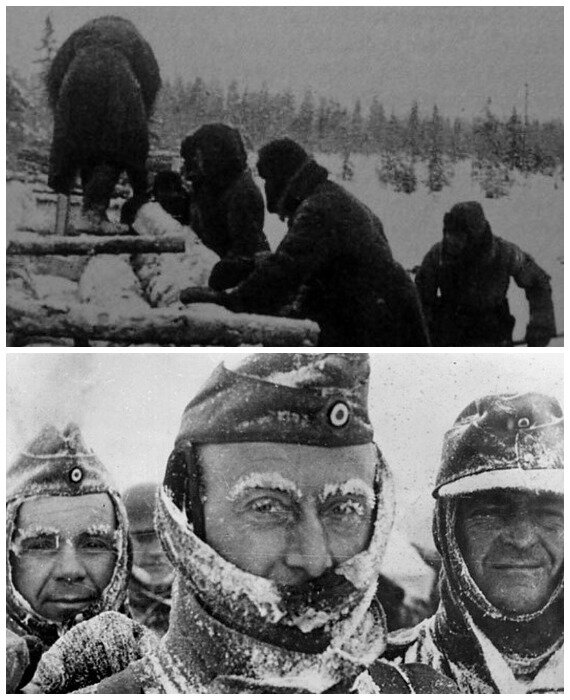

German soldiers were exposed to bitter subzero temperatures in Stalingrad during the winter of 1942–1943.

Hitler’s campaign in the south of the Soviet Union began as a major offensive in the Caucasus to secure oil for the Nazi war machine. Against the advice of senior commanders, who urged the unpredictable leader to focus on one objective, Hitler directed the 6th Army of Army Group South, under General Friedrich Paulus, toward Stalingrad, a vital industrial, communications, and transportation hub on the Volga River.

After the Luftwaffe bombed the city from the air, the Sixth Army pushed back almost the entire Red Army to the east bank of the Volga. But the Germans soon found themselves embroiled in brutal house-to-house fighting amid the city’s ruins.

“Stalingrad is no longer a city,” wrote one German soldier. “By day, it is a cloud of burning, blinding smoke. When night falls, dogs throw themselves into the Volga and swim desperately to the other bank. Animals flee this hell; even the hardest stones cannot endure it for long; only humans endure.”

Meanwhile, the Soviets took pleasure in bleeding the Sixth Army dry: “Even if we hadn’t had weapons, we would still have killed the people who came to take away our Volga with our bare hands,” said a Red Army sergeant.

On November 19, 1942, the Soviets launched “Operation Uranus,” a counteroffensive to encircle the already beleaguered Sixth Army and its allies. Three days later, the ring closed, trapping 250,000 soldiers in an area approximately 30 miles wide and 20 miles deep.

Because the Sixth Army could not receive sufficient air supplies from the Luftwaffe, it suffered from the incessant attacks. Temperatures dropped so low that machinery stopped working. Thousands of Axis soldiers suffered from frostbite and malnutrition. Paulus asked for permission to leave the pocket .

to escape, but Hitler refused. A rescue attempt by the German army from outside the encirclement failed.

At the end of January 1942, Paulus asked Hitler for permission to surrender rather than risk annihilation. “The Sixth Army will hold its position to the last man and the last bullet,” the Nazi leader replied, “and through its heroic perseverance will make an unforgettable contribution to building a defensive front and saving the Western world.”

On January 31, 1943, Paulus left waist-deep excrement in his battered headquarters in the heart of Stalingrad and surrendered to the Soviets. When Hitler heard the news, the often unpredictable Führer stared silently into his soup.