German Women Pows Hides 8 Breads In Her Uniform — Until Americans Say: “There Will Be More Tomorrow”

The Texas heat in June was suffocating, the air thick with the weight of endless sunlight. For us—twenty-four German women, captured and imprisoned by the Americans—every new day in this strange land felt like a cruel reminder of what we had lost. War had already taken everything from us—our homes, our families, our country. Now, we found ourselves in a camp, an unknown world of uniforms, guns, and iron-barred gates. But nothing had prepared us for what we encountered that morning in the mess hall.

It was the smell that hit us first. Warm yeast and the melting butter, swirling in the air like a forgotten memory. My eyes closed involuntarily as the scent wafted into the room, teasing us, reminding us of a time long past—before the war, before hunger. It was a smell so ordinary, so comforting, that it felt like an illusion.

The clang of metal trays and the soft murmur of voices brought me back to reality. I had not tasted fresh bread in years. The bread we had back home in Germany was a hard, gray, flavorless slab, sometimes not even worth eating. The bread of survival, not of comfort. But here, in this American mess hall, there it was—white bread, steaming, soft, warm. A smell that made my stomach clench painfully, an ache deeper than hunger.

For months, I had seen nothing but empty bowls and rationed scraps, never enough to fill the gnawing emptiness inside. The rumors we had heard back in Germany painted the Americans as cruel, indifferent, their prisons grim and filled with punishment. But the room before us now, with its shining trays of bread and fresh coffee, was nothing like the nightmare we had imagined.

I found myself gripping the strap of my canvas bag tighter, my knuckles turning white. This couldn’t be real. The bread was a luxury. No prisoner deserved this kind of kindness, not in wartime, not from the enemy. I felt a bitter wave of shame rise in my chest. How could the enemy offer us bread when our own country had failed to feed us? How could they smile, work, and laugh as though there was no war?

The soldiers moved like men who had never known hunger, their faces calm, their movements fluid. They placed tray after tray of bread on the counters, each loaf more perfect than the last. It was too much, too easy, too real.

One of the guards, a tall soldier with sandy hair and a friendly smile, caught my gaze. “Move along, ladies,” he said, not unkindly, gesturing for us to step forward.

It was strange to be spoken to with such care. I had been trained to hate men like him, to see them as the enemy. But here he was, treating me like a human being. The fear that had settled deep inside me for years began to fray around the edges.

The others seemed to feel it too, the slow dissolution of what we had been taught to believe. We stepped forward, slowly, hesitant, unsure if we should trust what we were seeing. I took a step closer to the counter, and then another, my heart pounding in my chest. There, on the tray in front of me, was the bread. It gleamed under the lights, golden and fresh. My hands, weak from months of deprivation, shook as I reached for it.

But the moment I touched the bread, something shifted. The air in the room seemed to hold its breath, and the weight of the past few years pressed down on me, heavier than it ever had before. We had been taught that food was not a gift from the enemy. We had been told that if we accepted it, we would lose our dignity. But here, the soldiers weren’t asking for anything. They were offering us what we had been denied for so long.

I took a slice of the bread, still warm to the touch, and held it in my hands. The bread felt like a relic from a past I could barely remember, like a piece of home that had been lost forever. The kindness, the generosity—it was overwhelming, too much to comprehend.

“Take more, if you like,” the soldier behind the counter said, his voice soft, kind. “There’s plenty.” He smiled at me, and for the first time in years, I didn’t feel like an animal.

A wave of emotion washed over me. I had always thought that kindness in war was a trick, a manipulation. The stories we had been told—about American brutality, their cruelty to prisoners—had painted them as monsters. But in that moment, in that mess hall filled with the smell of bread and the sounds of laughter, I realized that the greatest enemy had not been the soldiers in front of us—it had been the war itself, and the lies it had forced us to believe.

I looked around the room at the other women, their faces gaunt and drawn from months of starvation. They too were frozen in disbelief. We had been trained to hate these men, to fear them. But now, as they passed us tray after tray of food, I saw only something that had been missing for so long: humanity.

The soldier who had spoken to me earlier, Corporal Davis, placed another tray in front of me, this time with a steaming cup of coffee. I had not tasted real coffee in years, not since before the war began. The smell, sharp and bitter, filled my nostrils. I hesitated for only a moment before lifting the cup to my lips. The coffee burned my throat at first, but then the warmth spread through me, the comfort of it as unfamiliar as the bread.

The room was quiet, except for the crackling radio in the corner, playing soft jazz tunes. Glenn Miller. I had heard his music once, years ago, at a dance in Berlin, before the bombs fell and everything changed. Hearing it now, in a camp where I had expected only fear and violence, felt like a slap to my senses. How could music still exist in a world so ravaged by war? How could these men, these soldiers, still laugh and speak of home as though the world hadn’t collapsed around them?

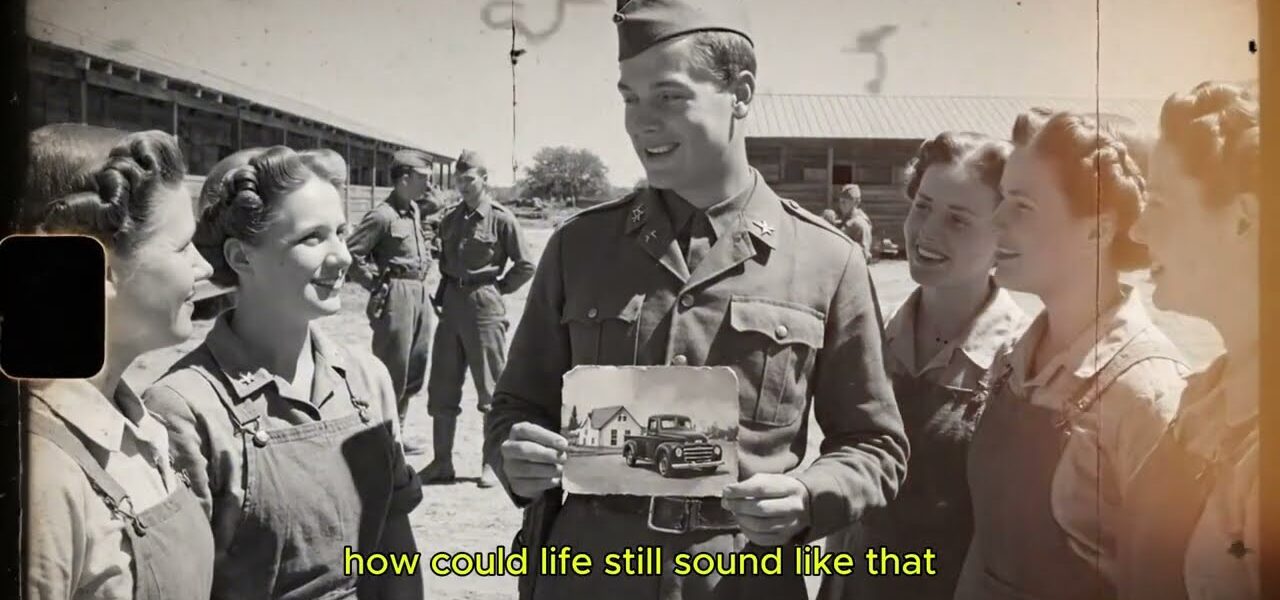

One of the soldiers came over to us, holding a small leather wallet. Without a word, he pulled out a photograph and handed it to me. It was a picture of his family, standing in front of a farmhouse in Kansas. A woman in a floral dress, two children holding tin lunch pails, and a man leaning proudly against a Ford truck. “That’s home,” he said quietly, tapping the picture. “Mom feeds everyone. Even folks passing through. Back home, we feed everyone.”

His words were simple, but they struck me with the force of a revelation. He wasn’t telling me this to show off, to make himself look better. It was simply the truth. In America, kindness was not exceptional. It was expected.

I looked at him, at the picture of the family I would never know, and something inside me cracked open. The contrast between this world and the world I had known—of hunger, fear, and scarcity—was too much to bear.

The soldiers here didn’t see us as enemies. They didn’t see us as soldiers to be defeated. They saw us as people—people who had been taught to fear them, but who, in the end, were simply trying to survive. They saw us not as prisoners, but as human beings. And that, more than any weapon, was what broke the walls inside me. It was kindness. Pure and simple.

As I stood there, surrounded by soldiers who had no reason to be kind to me, I realized something that shook me to my core. Kindness was not a weakness. It was strength. It was a weapon more powerful than any bomb, any gun, any tank. In a world torn apart by war, these men had chosen to be decent. They had chosen mercy over cruelty. And in doing so, they had become something more than soldiers. They had become a symbol of everything I had lost.

That night, lying in my cot, I closed my eyes and thought about what I had witnessed. I thought about the bread, the coffee, the laughter, and the kindness. The Americans had not just fed us; they had fed something inside us that had been starved for far too long—hope. And in that hope, I saw the truth: that no matter the war, no matter the hatred, kindness would always shine through.

In the days that followed, I began to see the soldiers for what they truly were—not monsters, not enemies, but human beings who had the courage to show mercy, even to those who had been taught to hate them. And as I stood there, watching them go about their work, laughing, talking about home, I understood that the true power of America wasn’t in its wealth, its armies, or its factories. It was in its decency, in its unwavering belief that mercy, even in the darkest of times, was stronger than fear.

And so, in that small mess hall in Texas, I witnessed the greatest victory of all—not the victory of arms, but the victory of kindness. And I knew, with all my heart, that the greatest generation wasn’t great because they had won the war. They were great because they had chosen mercy when it was hardest to do so. And that, above all, was their legacy.