Italian Officer Expected Slave Labor — Americans Let Him Run His Own Restaurant in the Camp Instead-Mex

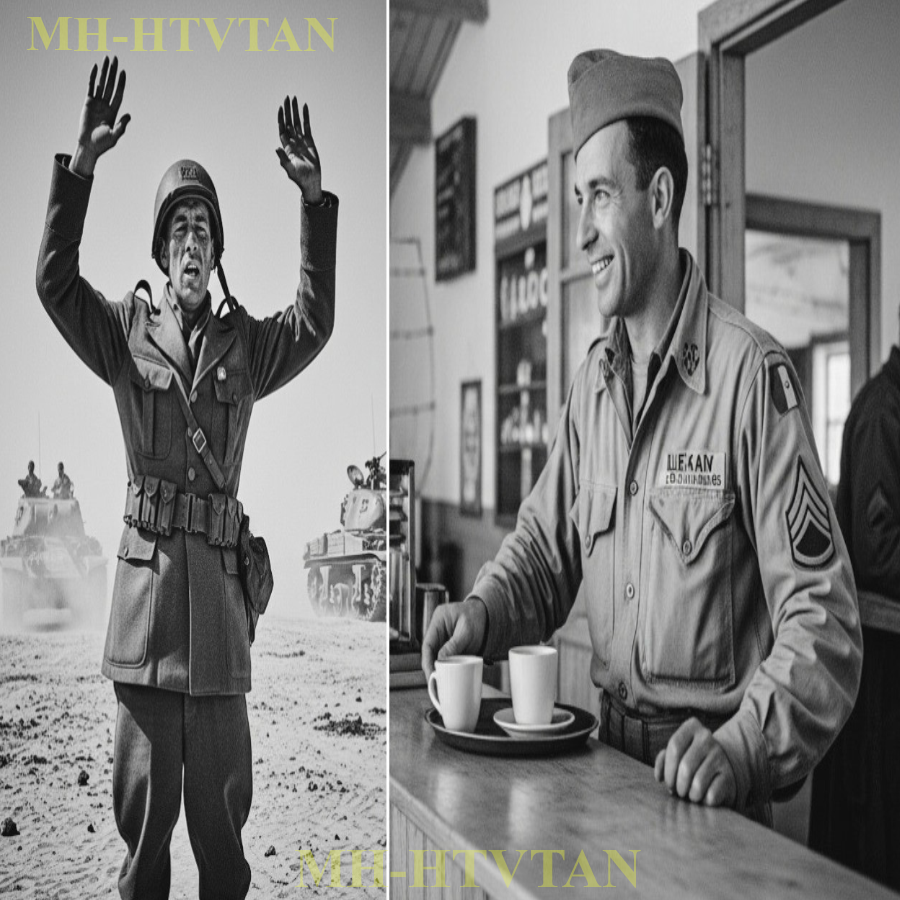

May 13th, 1943. Tunisia, North Africa. Captain Juspi Traante stood with his hands raised above his head, watching American tanks rumble toward him through clouds of desert dust. His throat was parched, uniform caked with sand and dried sweat. His mind raced with a single thought. He was certain he would die here.

For months, fascist newspapers had filled Italian minds with stories of American brutality. The Americans were savages, they said. Gangsters in uniform who tortured prisoners, worked them to death, shot them for sport. Jeppe had believed every word. Why would he not? They came from his own government. The American sergeant walking toward him had a hard face, eyes hidden behind dirty goggles.

Jeppe thought about the stories, the work camps, the beatings. He closed his eyes and whispered a prayer his mother had taught him as a child. He waited for the rifle butt to his face, the boot to his ribs. Instead, the sergeant lowered his rifle and pulled out a canteen and offered it to Juiceeppi. Jeppe stared at the canteen like it was a mirage. Water.

The American was offering him water. His enemy, the man who had just defeated him. His hands shook as he took it and drank. The water was warm and tasted like metal, but it was the most beautiful thing he had ever experienced. Jeppe searched the sergeant’s face for cruelty. He found none. What happened next over the following days, weeks, and months would completely shatter everything Jeppi Traumante thought he knew about Americans.

Within 6 months, he would not just be surviving in an American prison camp, he would be running his own restaurant. Jeppe’s journey into American captivity began with confusion. After surrendering in Tunisia, he and hundreds of other Italian soldiers were herded into a makeshift processing center in the desert.

Jeppe expected interrogation, beatings, starvation. Instead, they were given medical examination. A young American medic, who could not have been more than 20, cleaned the infected cut on Jeppe’s arm with surprising gentleness. The medic smiled and handed Jeppe a cigarette. An American cigarette. Lucky strike. They are fattening us up for harder work later.

Jeppe whispered to the soldier next to him. A private from Naples named Antonio. That evening they were given food. Not scraps, not moldy bread. Actual food. Canned beef. Crackers. Real coffee. not the chory substitute they had been drinking in the Italian army for months. Jeppe ate slowly, suspiciously, waiting for someone to snatch it away. No one did.

The next morning, they were loaded onto trucks for the port when an elderly Italian colonel stumbled while climbing aboard. Jeppe tensed, expecting the Americans to laugh or shove the old man roughly. Instead, a young private caught him and helped him up. Easy there, sir,” the boy said, steadying the colonel’s elbow.

Jeppe kept watching for the trap to spring. It never did. At the port of Oruron, they boarded a Liberty ship bound for America. The crossing took 16 days. They were cramped below deck with 800 other Italian prisoners of war, but they were fed twice daily. And one night, an American sailor with an Italian grandmother from Sicily tried speaking to them in broken Italian, asking about their families, showing them photos of his own.

Jeppe studied this young sailor carefully. He had an open face and an easy smile. He shared his cigarettes freely. He laughed when the Italian prisoners tried to teach him proper pronunciation. Jeppe could not reconcile what he was seeing with what he had been told. When the ship docked at Norfolk, Virginia on June 3rd, 1943, Jeppe stepped onto American soil, still uncertain of what came next.

The United States would hold 51,000 Italian prisoners during the war. Over 99% would survive to return home. In Japanese camps, barely 60% of Allied prisoners made it out alive. Jeppe was about to learn why. Camp Rustin, Louisiana, July 1943. located 60 mi east of Shrivefeport in Pine Country.

Jeppe’s first view of his new prison was surreal. Yes, there were guard towers. Yes, there was barbed wire. But beyond that, the camp looked less like a prison and more like a small town. Rows of wooden barracks, freshly painted, a messaul, a recreation area with volleyball nets. There was even a small chapel.

The pine forest reminded Jeppe painfully of the mountains north of Bolognia. The camp commander, Colonel James Mitchell, addressed them through an interpreter on their first day. “You are prisoners of war,” he said. “You will work as permitted under the Geneva Convention. You will be treated fairly and with respect, provided you follow camp rules.

You will be paid for your labor, 10 cents per day in Camp Script. Violence will not be tolerated. Escape attempts will be punished. But while you are here, you will be treated as soldiers, not as slaves. Jeppe glanced at Antonio. The trap would reveal itself eventually. He was sure of it. But weeks passed and the trap never came.

The work they were assigned was agricultural labor, picking cotton, harvesting vegetables on nearby farms. It was hard work. Jeppe’s back achd every evening. But they worked 8-hour shifts with breaks. And they received the same rations as American soldiers. More food than Jeppi had seen in the last year of the Italian army.

White bread, fresh meat, vegetables, real butter. Camp Rustin held 4,000 Italian prisoners of war. That 10 cents per day they earned was about $1.50 in today’s money. Not much, but more than they had earned in Mussolini’s army, and they could actually spend it at the camp canteen. By September 1943, Jeppe had been at Camp Rustin for two months.

The initial fear had faded, replaced by a strange sort of boredom. He was safe. He was fed. But he was also a prisoner, separated from his family, with no idea when or if he would see them again. One evening, Jueppy walked past the camp recreation hall and noticed something that stopped him cold. American guards and Italian prisoners were playing cards together.

Not forced interaction, not guarded hostility, just men playing cards, laughing, arguing over hands in a mixture of broken English and broken Italian. Jueppi watched, fascinated, as Sergeant Tom O’Brien, an Irish American guard from Boston, tried to explain poker to a group of Italians who kept trying to turn it into scopa.

You are doing it wrong. O’Brien laughed. No, no flush beats straight. In Italy, one prisoner countered, “We play properly.” They were smiling, all of them. Jeppe found himself pulled into the game. Within an hour, he was teaching O’Brien Italian card games while learning poker in return. O’Brien pulled out a battered photograph.

Two little girls in matching dresses smiling on a front porch. “Mary and Catherine,” he said. Seven and nine. Jeppe showed him the picture of Maria and little Sophia that he carried in his wallet, now creased and worn, three years old, holding a doll. “Pretty girls,” O’Brien said quietly. “This damn war. Neither man had to say more.

They both understood.” “Myangela looks like your Maria,” O’Brien continued. “Dark hair, nice smile. You will see her again, Captain. This war will not last forever.” Jeppe felt something crack inside his chest. Hope maybe or just the realization that this American sergeant saw him not as an enemy but as another man who missed his family.

That night, Jeppe could not sleep. He kept thinking about what his fascist officers had told him about Americans. Everything had been lies. But why? Why had his own government lied so thoroughly? What happened next would have been impossible to imagine in any German or Japanese prisoner of war camp. October 1943, a group of Italian prisoners at Camp Rustin approached Colonel Mitchell with an unusual proposal.

Several of them had been cooks, bakers, and restaurant workers in civilian life. They wanted to open a small cafe in the camp. Nothing elaborate, just a place where prisoners could spend their camp script on coffee, pastries, and simple Italian meals. Jeppe expected an immediate rejection. This was a prison camp.

You did not run businesses in prison camps. Colonel Mitchell surprised everyone. Submit a proper proposal, he said. Show me your business plan. If it is reasonable and does not violate camp regulations, I will consider it. Juseppe, who had managed his family’s tratoria in Bolognia before the war, joined the planning committee.

Working with Antonio and three other Italian prisoners, including a baker from Rome named Franco and a chef from Milan named Roberto, they drafted a real proposal. They would use their combined camp script earnings to buy basic ingredients from the base commissary. They would prepare food in a designated area of the messaul during off hours.

They would price items reasonably. Any profits would be split among the workers and reinvested in the business. Colonel Mitchell approved it. The Cafe Italiano opened in November 1943 in a corner of the camp recreation hall. It was modest, a few tables, a small preparation area, a handpainted sign.

But to the Italian prisoners of war, it was a miracle. Jeppe and his partners prepared real Italian coffee, biscati made with eggs purchased from the commissary, and simple pasta dishes. The cafe became a gathering place where Italian prisoners could sip espresso and pretend for a few moments that they were back home.

But something even more remarkable happened. American guards started coming, too. Sergeant O’Brien became a regular customer. He would sit with Jeppe drinking what they both knew was a terrible American approximation of cappuccino, talking about their families, their lives before the war. Other guards followed. Jeppe charged 15 cents for espresso.

50% more than the camp cantens American coffee. The guards paid it gladly. Worth every penny, Captain O’Brien would say, sipping the bitter brew. Reminds me of Boston’s North End. Soon the cafe was a genuinely integrated space. American guards and Italian prisoners sharing tables, sharing stories, sharing humanity. Jeppe would stand behind his small counter making coffee and marvel at the absurdity of it all.

He was a prisoner of war running a restaurant in an enemy prison camp. The Americans were paying him. They were protecting his business. They were treating it seriously, professionally, as if he were a legitimate proprietor rather than a defeated enemy soldier. In Italy, he wrote to Maria in a letter that would take months to reach her through Red Cross channels.

They told us Americans were savages without culture. But these men respect craftsmanship. They appreciate good food. They treat me like a human being, not an animal. I do not understand them, but I am beginning to admire them. Later surveys would show that 85% of Italian prisoners of war left American captivity with positive views of the United States.

Many credited their camp experiences with opening their eyes to democratic values. Jeppe was one of them. Three incidents crystallized Jeppe’s transformation from fearful prisoner to something else entirely. December 1943, Franco the baker received news that his brother had been killed fighting in Italy. He collapsed in grief.

Unable to work, Jeppe expected the guards to force him back to the kitchen. Instead, Colonel Mitchell granted Franco 3 days of mourning, leave unpaid time to grieve. O’Brien and several other guards attended a small memorial service the Italian prisoners held in the chapel. I am sorry for your loss, O’Brien told Franco, his hand on the weeping man’s shoulder.

War is hell for everyone, even in their humanity. The Americans maintained principles. February 1944, a new prisoner arrived at Camp Rustin, a hardcore fascist officer who immediately began causing trouble. He tried to intimidate other prisoners into refusing work, calling them traitors for cooperating with Americans. Jeppe watched nervously as Colonel Mitchell handled the situation.

The fascist expected martyrdom, perhaps even wanted it. He got solitary confinement and a stern lecture about camp rules. No beatings, no torture, just firm, fair discipline. Jeppe understood something profound. The Americans did not need brutality to maintain order. They had something more powerful. Consistent rules applied equally to everyone.

March 1944, Jeppe received his first letter from Maria. It had taken nine months to reach him through Red Cross channels. She and Sophia were alive, hungry, frightened by the Allied bombing of Bolognia, but alive. Jeppe read the letter 17 times, tears streaming down his face. That evening, Sergeant O’Brien found him in the cafe, staring at nothing.

“Bad news from home?” O’Brien asked gently. Jeppe shook his head. Good news. My family is alive, but Bolognia is being bombed. He looked up at O’Brien. American bombs. He expected justification. Perhaps mockery. Instead, O’Brien’s face was sad. I am sorry, the sergeant said quietly. I am sorry your family is suffering.

I am sorry about all of it. War should not happen to families. Jeppe stared at this American sergeant. this man whose country’s bombs were falling on Bolognia, whose planes had killed Franco’s brother, apologizing with genuine sorrow. In that moment, Jeppe understood something that would stay with him for the rest of his life.

The enemy was not evil. The enemy was just the enemy. Men doing what their countries asked. Men who would rather be home with their families. “You are not what they told us you were,” Juspe said in halting English. O’Brien smiled sadly. No one ever is, Captain. No one ever is. Jeppe nodded. He finally understood.

The treatment Jeppe experienced was not an anomaly. It was American policy. In 1942, as the United States prepared to receive thousands of access prisoners of war, the War Department made a strategic decision. America would strictly adhere to the Geneva Convention, not just in letter, but in spirit. The Pentagon understood something profound. Reputation mattered.

Every Italian soldier who surrendered and lived to tell about good treatment was a walking advertisement that undermined enemy propaganda. Why fight to the death if surrender meant safety, food, and respect? But beyond strategy, there was genuine belief at work. Men like Colonel Mitchell believed in fundamental human dignity.

They saw the Geneva Convention not as an inconvenient rule, but as a moral framework that separated civilization from barbarism. This philosophy extended throughout the American prisoner of war system. Of the approximately 425,000 access prisoners of war held in camps across the United States, 51,000 Italians, 370,000 Germans, 4,000 Japanese.

The vast majority received similar treatment. They worked. They were paid. They had access to recreation, education, and religious services. The International Red Cross conducted regular inspections. Their reports consistently noted good conditions, adequate food, proper medical care, and adherence to Geneva Convention standards.

Meanwhile, approximately 90,000 American prisoners of war were held in German camps and 27,000 in Japanese camps. The experiences were vastly different. In German stallings, conditions were harsh, but generally within convention bounds. In Japanese camps, conditions were horrific starvation rations, routine beatings, forced labor, medical neglect.

Actions spoke louder than words. America’s adherence to international law sent a message far more powerful than any propaganda broadcast. We take our principles seriously, even when no one is watching. even when our enemies do not reciprocate. Jeppe learned these facts after the war. They confirmed what he had experienced firsthand.

May 8th, 1945, the war in Europe ended. Jeppe stood in the campyard at Rustin, listening to the announcement over the loudspeaker and wept. Not from joy, the joy would come later. In that moment, he wept from relief and from uncertainty. Repatriation took time. Jeppe remained at Camp Rustin until August 1945, continuing to run Cafe Italiano, continuing to serve coffee to American guards who had become improbably his friends.

On his last day at the camp, Sergeant O’Brien gave him a gift, a small American flag and a note. Remember, O’Brien had written that enemies can become friends. Come back to America someday as a visitor this time. Jeppe sailed back to Italy in September 1945. His duffel bag full of American coffee and chocolate bars for Sophia. He found Bolognia damaged but recovering.

Maria and Sophia had survived the war thin and frightened but alive. September 1945. Bologonia. Jeppe knocked on a door he had dreamed about for 2 years. It opened. Maria stood there older, thinner, but alive. Jeppe. He dropped his duffel bag. Chocolate bars scattered across the floor. Gifts for Sophia he had forgotten he was holding.

“I am home,” he whispered. The reunion was everything he had dreamed of. But Jeppe carried something else back to Italy, a transformed world view. In 1946, Jeppe reopened the family tratoria in Bolognia. He named it Cafe Americano in honor of his experience. The restaurant became a gathering place for former Italian prisoners of war who had been held in American camps.

They would meet, drink Americanstyle coffee, which Jeppe had learned to make properly at Camp Rustin, and talk about their experiences. We were the lucky ones. Jeppe would tell his daughter Sophia years later, “We saw the real America, not the propaganda version, not the Hollywood version, the real thing.” And it changed us.

Jueppy never forgot his promise to Sergeant O’Brien. In 1952, he traveled to America as a tourist, bringing Maria and 12-year-old Sophia. They visited Boston, where O’Brien, now a police officer, gave them a tour of the city. The two former enemies embraced like brothers. Jeppe maintained correspondence with O’Brien until the sergeant’s death in 1979.

He attended the funeral, traveling from Bolognia at age 68 to honor the man who had shown him that enemies could become friends. Jeppi’s story was repeated thousands of times across postwar Europe. Italian prisoners of war who had experienced American captivity returned home with changed perspectives on democracy and American values.

Many became active in Italy’s post-war reconstruction and democratic reforms. They had seen how democratic institutions worked in America, not perfectly but effectively. They had experienced fair treatment under rule of law. They understood that authority did not have to mean brutality. When the Marshall Plan brought American aid to rebuild Europe, including former enemy nations, many Italians were not surprised.

Jeppe certainly was not. Of course, the Americans help rebuild. He told his skeptical neighbors. I told you they are not conquerors. They are different. The strategic wisdom of treating prisoners of war well paid enormous dividends. Italy became a crucial American ally in the Cold War. Former enemy soldiers like Jeppe became ambassadors for American values in their communities.

The goodwill generated by humane treatment lasted generations. America made a choice during World War II. Respond to brutality with brutality or maintain principles even toward enemies. That choice paid dividance for generations. Italian soldiers stopped fighting to the death because surrender meant survival. Former enemies became cold war allies.

The Marshall Plan succeeded because America had already proven its values were genuine. Jeppe’s restaurant was not just an anomaly. It was proof of concept. In 1983, a historian from the University of Bolognia interviewed Jeppe for an oral history project. Jeppe was 72, still running Cafe Americano with Sophia’s help.

People ask me if I feel grateful to the Americans, Jeppe said. That is not quite the right word. Gratitude implies charity. What I feel is respect. They did not spare my life out of pity. They treated me according to rules, according to principles they believed in. They showed me that civilization means keeping your humanity even toward your enemies.

I tell my grandchildren about the time I was an enemy prisoner who ran a restaurant in Louisiana. They think I am making it up. It sounds impossible, but it happened. And it happened because Americans believe that even enemies deserve to be treated as human beings. That belief, that simple powerful belief, that is what really won the war.

Not just the battles, the idea behind the battles. Jeppe Traumante died in 1991 at age 80. At his funeral, Sophia read from her father’s memoir. The last entry described his first morning at Camp Rustin, drinking coffee given to him by an American guard, realizing that everything he had been told was wrong. In that moment, Jeppe had written, “I stopped being a fascist.

I started being simply a man again.” Jeppe Traumante raised his hands in surrender on a North African battlefield, expecting death, torture, and slave labor. He had been told Americans were savages without honor or mercy. Instead, he found humanity, respect, the opportunity to run a small restaurant in a Louisiana prison camp, serving coffee to the very guards who watched over him.

He found men like Sergeant Tom O’Brien, who showed him photos of their families and treated him not as an enemy, but as another man far from home. This was not just American military doctrine. This was American character. Jueppi returned to Italy transformed. He spent the rest of his life telling anyone who would listen about the Americans who proved that enemies could become friends, that principles mattered even in war, that civilization meant maintaining humanity even toward the defeated.

He expected chains. He got a chance. And that made all the difference. If you are a veteran or if your father, uncle, or grandfather served in World War II, they had stories like this. Stories of unexpected humanity in impossible circumstances. Share those stories in the comments before they are lost.

These are not just history. They are lessons we still need. Next time we will explore another story of an enemy who expected the worst and found something else entirely. the German pilot shot down over Texas who helped build the town’s first hospital. Until then, remember Jeppe’s lesson. How we treat our enemies defines not just who we are in war, but who we become in peace.