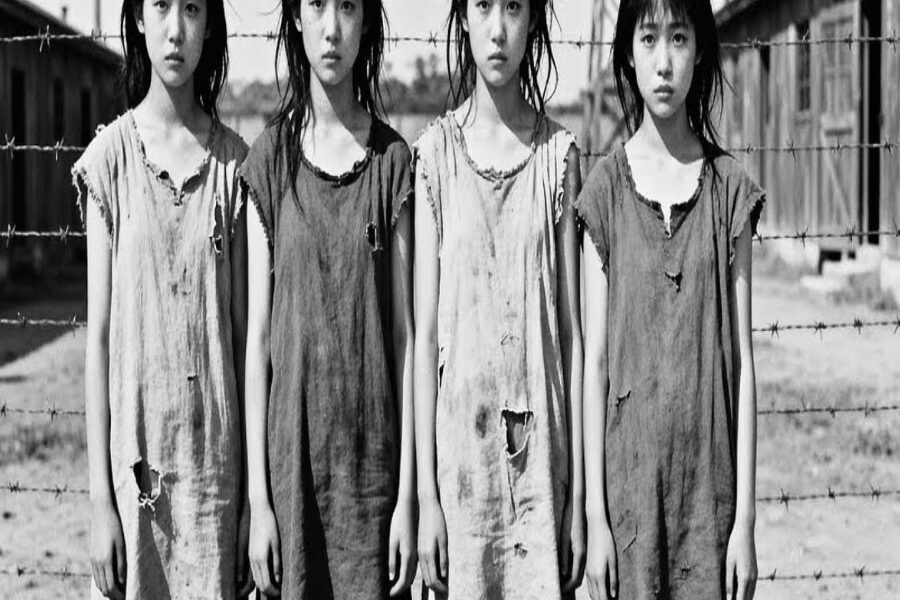

August 15th, 1945. Japan has just surrendered. But inside a small bamboo hut in the Philippines, fear still hangs heavy in the air. Young women forced to serve as so-called comfort girls sit in silence, waiting for what they believe will come next. They expect the same cruelty they had endured for years.

But something shocking happens instead. American soldiers walk in not with threats, not with orders, but with food, soap, even music. The women are stunned. For the first time, no one even tries to touch them.

On the afternoon of August 15th, 1945, Emperor Hiito’s voice broke across radio waves, filtered through static, declaring surrender in language so formal many could not grasp its meaning at first. In Tokyo, some wept, others rioted. But hundreds of miles away in the sweltering huts of Luzon, the words meant little to the young women who sat on reed mats, fanning the thick air. For them, war had not ended.

The guards still came, the doors still closed, and the dread of footsteps still measured their days. The paradox was cruel. For years, uniforms had meant possession, orders, and the certainty of being touched whether they wanted it or not. The system that held them was both vast and banal.

Comfort stations stretching from Burma to Shanghai, staffed by women who were told they were serving an empire, when in truth they were captives of its machinery. Numbers vary, but even the most cautious historians estimate between 50,000 and 200,000 women passed through this network. Many were Korean. An Allied report in 1944 suggested as many as 80 to 90%, though Chinese, Filipino, Indonesian, Taiwanese, and Dutch women were also forced into service. Ledgers tracked them like inventory.

Some were assigned to barracks on the outskirts of Manila, others to makeshift huts in the jungles of Burma. A Japanese Army medical officer once described the system in chillingly bureaucratic terms. Women were inspected, listed, and rotated to meet quotas.

Survivors later recalled being lined up for weekly checks, where humiliation came not only from the proddding of doctors, but from the tally marks that followed. One woman, remembered decades later, said simply, “We were not people. We were schedules.” The sensory world of these places was unforgettable. The acrid smell of disinfectant mixed with sweat. The clatter of mamm est tins outside walls of bamboo. The faint incense burned by some women trying to mask the odor of fear. Nights were the worst.

The drone of insects outside contrasted with the jarring rhythm of boots on gravel, signaling another entry, another round. Some women faced 15 to 30 men in a single day. According to testimonies later gathered by US medics and international commissions.

The contrast between the emperor’s lofty surrender and the grinding reality inside these rooms could not have been sharper. But even before surrender, cracks in the system were showing. Supplies ran thin. Soldiers, desperate and hungry, sometimes shared their rice rations with the women, not out of kindness, but fatigue. In those final months, diaries suggest a strange collapse of formality.

Japanese guards too exhausted to enforce order. Women clinging to scraps of humanity in whispered songs. A Korean survivor, Kim Haksun, who would speak publicly decades later in 1991, remembered that by the war’s last days, the soldiers were frightened of losing, but we had no place to go. We were trapped in their fear and our own.

Statistics painted the larger picture. By summer 1945, the Imperial Army had scattered comfort stations across at least 10 territories. Manila alone had dozens, serving thousands of troops. Medical records seized by the Allies later indicated that over 70% of women were malnourished, more than half suffered from veneerial disease, and almost all bore permanent scarring, both physical and psychological.

These figures, buried in archives for years, revealed the systems true cost. An army’s illusion of control, paid for by a generation’s broken lives. And yet, in August 1945, the machinery suddenly stopped. Orders from Tokyo no longer carried force.

The guards who had ruled these huts listened to the radio, their faces blank, their authority dissolving in static. Outside, allied convoys rolled closer, their diesel fumes mingling with the humid air. The women inside did not yet know what to expect. They only knew that a change was coming, and with change came terror. What kind of men would arrive? Would they be harsher than the last? The sound of new boots on gravel brought silence.

Paper screens quivered. Then instead of commands came the creek of crates being lowered, the hiss of a harmonica note, the metallic pop of a tin being opened. The paradox deepened. War had ended. Yet for the women inside, the greatest shock was not defeat, but the sudden absence of the very violation they had come to expect. But this was only the beginning.

The paradox of liberation could not be understood without first tracing the machinery that had trapped these women in the first place. The Japanese military did not stumble into the comfort system by accident. It was engineered, calculated, and expanded with cold precision. The origins dated back to the 1930s. After the brutal Nanjing massacre in 1937, when widespread reports of mass sexual violence shocked even Japan’s allies, the Imperial Command sought to regulate soldiers impulses. Their solution was not to end abuse, but to organize it.

The euphemism chosen was eanjo, comfort station. By the time the Pacific War widened in 1941, these stations had become as integral to the Japanese army as supply depots or field hospitals. Transports carried women across borders as though they were munitions.

Korean teenagers were told they would work in factories or hospitals only to find themselves herded into trains and ships bound for Southeast Asia. Filipino girls were seized during village raids. In the Dutch East Indies, colonial families were torn apart, their daughters taken as spoils. By 1942, stations existed in Shanghai, Nanjing, Singapore, Burma, the Philippines, and even the Pacific Islands. Ledgers survived in fragments.

They showed quotas, rotations, and payments that were rarely, if ever, given to the women themselves. Historians estimate that at the peak of the system, as many as 400 stations operated simultaneously. If one station averaged 20 women, the scale was staggering. Yet official documents often reduced this vast network to columns of numbers. Women 23, clients per day, 300, medical inspection weekly.

The cruelty lay in the contrast. Publicly, Japan proclaimed itself the guardian of Asian unity under the slogan Asia for Asians. Privately, its armies sustained themselves on a system of systematic exploitation. The paradox was clear. Soldiers were told they were protecting Asian sisters from Western domination, even as those same sisters were locked into huts and treated as consumable resources. They spoke of honor, recalled one Chinese survivor decades later.

But they fed their honor on our bodies. Statistics bear this out. In 1944, an Allied intelligence report based on captured documents suggested that up to 90% of comfort women were Korean. Other studies placed the total number of women exploited at between 50,000 and 200,000, a margin that itself reflects the deliberate destruction of records by retreating Japanese forces.

Even the lowest figures dwarf the population of entire wartime towns. Sensory fragments from testimony sharpened the picture. Survivors remembered the suffocating smell of disinfectant sprayed between visits, the taste of watered down rice grl, the scratch of rough blankets in unventilated huts.

Some described the heavy silence after each day’s appointments broken only by the coughs of guards, or the scribble of pens marking tallies in notebooks. To outsiders, these were rests. To those inside, they were prisons without locks, where escape was impossible because the entire continent had been wired into the same machine. Occasionally, resistance flickered.

Women feigned illness, shared whispered strategies for slowing down inspections, or carved small marks into wooden walls to count the days. Yet, each act of defiance risked beatings or worse. One testimony described a girl of 16 who tried to run during a transfer in Burma. They brought her back and after that no one spoke her name again.

By 1945 shortages and exhaustion gnored at the system. Soap and medicine grew scarce, rations shrank and the promised inspections became peruncter. Diseases spread unchecked. In Manila, captured Japanese documents revealed that more than half of women were infected with veneerial disease and up to 70% showed signs of malnutrition.

The machinery was breaking down, but not from mercy, from logistical collapse. It was into this disintegrating system that American soldiers would soon step. They carried crates, cigaras, retas, and radios, expecting to find enemies or collaborators. Instead, they found young women huddled in bamboo huts, reduced to numbers in notebooks. For the women, the paradox was about to turn again.

The same military culture that had taught them to expect violation would suddenly dissolve, replaced by an occupying force that, to their astonishment, did not even touch them. What they saw next would defy every rule they had been taught to believe. For the women inside the stations, life had been reduced to ledgers long before the surrender.

They were not counted as daughters or sisters, but as entries in notebooks. The Japanese army’s bureaucracy transformed intimacy into arithmetic and every tally marked another fragment of humanity stripped away. One surviving ledger from Burma listed only numbers. Women 14 visits per day, 280. Broken down, that meant an average of 20 men for each woman every day.

Medics later interviewed survivors who described similar figures. 15 to 30 visits daily with no reprieve except illness, which itself could trigger punishment. “We were not people, we were shifts,” one Korean survivor recalled decades later. “Her words captured the paradox.” The army called these women comfort, but their own comfort had been completely erased.

The sensory details haunt the records. Women spoke of the smell of carbolic acid burning their skin during weekly inspections, of the rustle of paper screens that never closed tightly enough to offer privacy, of the scratchy car uniforms brushing past them like a signal of inevitability.

One Dutch captive later told investigators the sound of boots was worse than any gunfire. It meant the night was beginning again. Inside, memories of their former lives were fragile, clutched like talismans. A Filipina survivor described humming folk songs in Tagalog while waiting for soldiers to leave, hoping to remind herself she still belonged somewhere. A Korean girl of 17 carved a bird into the wooden frame of her mat, a symbol of flight in a place where escape was impossible.

These small acts of remembrance were paradoxes themselves, moments of humanity kept alive inside a system built to extinguish it. The bureaucracy added insult to injury. Women were issued tokens as if they were vendors, each soldier handing one over before his turn. Some stations even kept receipts. Soldiers received stamped passes confirming their visit, a grotesque parody of civility layered a top systemic abuse. The Japanese officers who supervised these huts reported their efficiency in clean clinical language.

One document described how women could be rotated every two months to maintain morale. The casual cruelty of the phrasing left no room for the screams it concealed. Numbers reveal the cold scope. By 1943, an estimated 400 comfort stations operated across Asia.

If each housed 20 women, that meant roughly 8,000 women at any one time. Multiplied over years of war and transfers, the totals swelled into the tens of thousands. Survivors later testified that some girls were as young as 12, their bodies not yet able to bear the weight of the systems demands. Medical records found by US Army units in the Philippines after liberation showed veneerial infection rates above 50% and evidence of forced abortions conducted without anesthesia.

Yet amid this brutal arithmetic, paradoxes of survival emerged. Some women described guards who smuggled them extra rice balls, not out of kindness, but because disease made them less useful. Others remembered fleeting alliances, one girl distracting a soldier so her friend could rest for an hour. Survival required such improvisations, but each act was swallowed again by the machinery of exploitation.

When the emperor’s voice crackled over the radio on August 15th, 1945, the ledgers did not close. Guards continued their routines for days, uncertain of orders. Women, trained by fear to obey, kept silent. The sound of boots still haunted the night, though now those boots carried hesitation.

In the distance, however, new engines were approaching. Louder, heavier, unfamiliar. American convoys were rolling through Manila’s outskirts, and with them came a different kind of paradox. soldiers who brought crates of food instead of ledgers, and who measured their presence not in tokens exchanged, but in gifts offered.

For the women staring through bamboo screens, waiting, disbelief became the new form of fear. They braced for what they knew, and instead encountered the unimaginable. The first signs of liberation were not words, but smells and sounds. Diesel fumes of American trucks drifted into the compounds, mingling with the damp, musty air of bamboo walls.

Instead of the sharp bark of Japanese commands, the women heard unfamiliar draws and laughter, the clatter of metal crates being lowered onto gravel. For women conditioned to brace their bodies at the sound of boots, the pause was unbearable. They expected the routine to resume. Orders, inspections, the inevitable touch.

But what entered through the paper screens was not demand, but the metallic pop of a tin can being opened. Witnesses later described the moment with disbelief. A Korean woman recalled. They set down food, real food, and stepped back. We did not understand. We thought it was a trick. The soldiers offered soap, cigarettes, even a harmonica. A Filipino survivor remembered the sweet, sticky taste of canned peaches, so foreign to her tongue that she wept while eating them. The paradox was crushing.

Uniforms still filled the doorways, but for the first time, no hands reached for them. Some American soldiers tried to speak. Few shared a common language, so gestures did the work. A bar of chocolate unwrapped, a cigarette lit and handed across with an awkward smile, a harmonica note echoing into the humid air. Each small act carried more weight than any proclamation of surrender.

One man put his rifle against the wall and played music, recalled a Dutch captive, and we realized he would not touch us. That sound was freedom. The contrast could not have been sharper. For years, comfort stations had functioned as prisons without locks, where women’s bodies were claimed nightly in the name of discipline. Now suddenly the very men who could have exercised the same power chose restraint. The shock was physical.

Some women recoiled, convinced violence would follow if they react. Heed for the food. Others froze, unable to imagine that touch could be withheld. We thought they were waiting, said one survivor, waiting to show kindness, then take what they wanted, but they never did.

The statistics from US Army medical teams underlined the scale of what they found. In Manila, reports noted that more than half of the women liberated suffered from veneerial infections and over 70% showed signs of malnutrition. Many were too weak to stand when soldiers arrived.

Army doctors recorded that several weighed less than 80 lb, their ribs protruding, their skin paper thin from years of deprivation. To the medics, this was evidence of systemic exploitation. To the women, the first taste of canned peaches or a spoonful of condensed milk was almost unbearable. “It was too sweet,” one said later. “We were not used to sweetness anymore.

The sensory impressions of liberation stayed with them. The sharp bite of soap on skin scrubbed raw after years without it, the heavy fabric of American ration sacks repurposed as blankets. the strange twang of English words echoing in rooms that had known only commands in Japanese. One Korean girl later recalled, “The first time I washed with real soap, I cried.

My body remembered what it was like to be clean. Trust, however, did not come easily. Trauma had trained them to expect betrayal. Even as days passed without violation, many women refused to sleep, waiting for the inevitable reversal.” American soldiers, unprepared for the depth of suspicion, often left gifts at the doorway and retreated, not realizing that this very act, leaving women alone, untouched, was the greatest gift of all.

The paradox of restraint became its own kind of shock. In a world where uniforms had always meant possession, the refusal to touch was revolutionary. And yet this revolution began not with speeches, but with soap, peaches, and a harmonica played in a bamboo hut as the war slipped into silence.

But behind those simple gifts lay another layer of the story, the clinical records, interviews, and statistics that sought to measure suffering in numbers, even as no number could capture the weight of years stolen. The crates of food, and the harmonica songs told one story, the paperwork and reports told another.

For the US Army, the liberation of women from Japanese comfort stations was not only a humanitarian shock, but also a trove of intelligence. Medical officers, psychological warfare units, and occupation officials moved quickly to record what they found. Their language was clinical, almost sterile, a sharp contrast to the flesh and blood suffering it attempted to capture. In one report from Manila in late 1945, army medics noted that approximately 75% of females examined showed evidence of venerial disease, malnutrition, or chronic infection.

Another document recorded average body weights as low as 80 lb with several women showing signs of anemia and vitamin deficiency. A field officer wrote bluntly, “These girls have been worked beyond the point of collapse. numbers piled onto pages. Height, weight, pulse, infections, pregnancies terminated. In the cold light of the examining tent, human beings were once again reduced to figures. The paradox here was striking.

For years, Japanese officers had kept ledgers tallying clients per day. Now, American medics compiled charts noting lesions per case or caloric intake needed. Both systems turned bodies into data, though one sought to exploit while the other aimed to heal.

Still, survivors later remarked on how even compassion felt distant when filtered through clipboards. “They measured us like cattle,” one Korean woman recalled in a 1990s testimony. “But at least this time, the measuring came with medicine.” “Sensory memories sharpened the contrast. Survivors described the sting of iodine on open sores, the metallic taste of quinine tablets pressed into their palms, the cold steel of thermometers under their tongues.

Some wept not from pain but from the realization that someone intended to cure rather though and control. An army nurse later wrote in her diary, “They had forgotten what gentleness felt like. Even a bandage was met with suspicion. Psychological warfare teams also gathered testimony.

They interviewed women about Japanese soldiers morale, movements, and behavior, hoping to mine trauma for strategic insights. In one declassified transcript, a Filipina captive described soldiers growing more desperate, more violent as supplies dwindled in 1945. Another Korean girl told interrogators, “They said, “We were serving the emperor, but they served themselves.” Such statements reinforced Allied propaganda that painted the Japanese military as brutal and dishonorable.

For the women, however, telling their stories meant reliving the very orals they longed to forget. Statistics multiplied. Allied intelligence estimated that between 50,000 and 200,000 women across Asia had been subjected to the system.

Some scholars placed the figure higher, though deliberate destruction of records made certainty impossible. In 1946, occupation officials in Japan reported that entire villages in Korea and Taiwan had been stripped of young women. The scale was continental. The paradox deepened again. Liberation brought medicine, food, and attention. Yet, it also brought new forms of objectification to the American army.

The women were both victims to be healed and evidence to be cataloged. Compassion was real, but it was bureaucratized. We were finally free, said one survivor. But freedom still came with forms to fill. Still, the difference was undeniable.

For the first time in years, needles pierced skin to vaccinate, not to punish. Pills were given to cure, not to control fertility. Charts were kept to restore health, not to ration exploitation. The same tools, pens, ledgers, clinical notes that had once erased their humanity now imperfectly began to rebuild it.

Yet the most enduring memories of liberation were not written in reports or sealed in archives. They lived in the smallest gestures. The soldier who tied a sandal strap. The medic who handed over a clean cloth. The nurse who lingered just long enough to ask softly, “Are you all right?” These fragile mercies began to restore something greater than health. They began to restore trust.

Trust, however, did not arrive all at once. It came haltingly in fragments carried by gestures so small they might have gone unnoticed in any other context. Survivors later remembered how the most ordinary acts felt extraordinary after years inside the machinery of coercion. One young woman described being given a bar of soap.

She turned it over in her hands again and again, half expecting it to be taken back. The soldier who offered it did not reach toward her afterward. He simply moved on. “It was the first gift I had received that did not ask for my body in return,” she recalled.

Another remembered how an American private carved tiny birds out of scrap wood, leaving them near the door of the hut without saying a word. “The small figures, rough and uneven, carried more tenderness than years of forced attention. Food too became a language of its own. The sharp sweetness of canned peaches, the heavy warmth of bread thick with butter. These tastes cut across fear.

Women spoke of sitting in silence, clutching tins, too overwhelmed to eat at first. Slowly, the act of swallowing became an act of reclaiming life. It was like tasting freedom, one Filipina survivor said decades later. There were still layers of mistrust. Some women flinched when approached, expecting command or violence, others recoiled from medical inspections, fearing another ledger of quotas.

Yet, as days stretched into weeks, the rhythms of kindness began to outweigh the reflexes of terror. Bandages were applied without orders, wounds were cleaned without demand. One army nurse later admitted in her diary that she could do little more than sit beside the women in silence, offering her presence as proof that not every uniform carried cruelty. Fragile friendships formed.

A few survivors began to laugh again, though softly, as if testing whether the world would punish them for joy. A harmonica tune. At dusk, a soldier playing a half-forgotten folk song drew shy smiles. A girl traced the melody with her finger in the air, unwilling to speak, but unwilling to let it pass unnoticed.

These small mercies stitched something essential. Agency. For years, decisions had been stripped away, when to eat, when to sleep, when to endure. Now, even the choice to refuse a ration or to keep a carved bird as her own became an act of ownership. A survivor later wrote in her testimony, “For the first time, I remembered that I had a name. Yet the paradox lingered.

Gratitude and suspicion coexisted. Some survivors could never see American soldiers as anything but another occupying force, however gentler their methods. Others clung fiercely to the gestures, believing that even in war, humanity could surface. What united them was the awareness that healing was not immediate.

It was a process measured not in charts or calories, but in moments of dignity returned in those huts and field hospitals. Mercy did not erase what had happened. Nothing could. But it did plant the possibility of a future beyond survival. For the women, it was not a rescue story written in bold headlines, but a fragile beginning carried in soap, peaches, wooden birds, and the memory of music drifting into night. When the war ended, silence followed like a shadow.

For the women once called comfort girls, liberation did not bring immediate recognition. Their suffering was largely invisible in the grand narratives of victory and reconstruction. The Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal convened in 1946 cataloged massacres, chemical experiments, and forced labor with clinical precision.

Yet the system of enforced prostitution, vast and meticulously organized, received scant attention. It was as if the ledgers that once reduced them to quotas had been burned along with the evidence. Statistics were there for anyone who looked. Historians estimate between 50,000 and 200,000 women were forced into Japan’s military brothel system across Asia.

Registers showed train loads of women moved from Korea, the Philippines, China, and Burma. Medical officers kept reports on veneerial infection rates and pregnancy terminations. Yet in tribunal records, the words comfort station rarely surfaced. Justice had chosen its categories of crime, and sexual slavery did not fit easily into the boxes drawn in 1946. Many survivors tried to bury the past, forced into silence by stigma.

In Korea, families often disowned daughters who returned. In the Philippines, women married quietly, telling no one. Shame was a weapon as powerful as the bayonet. One Korean survivor later admitted, “I did not tell even my children. I lived like a ghost in my own house. But silence is never complete.” In 1991, nearly half a century later, the first testimonies broke through.

Kim Haksun, a Korean survivor, stepped before cameras and declared that she had been taken at age 17 and forced into military brothel. Her words ignited a global reckoning. Others followed. Filipino lolas grandmothers stood before microphones, their voices quivering but insistent. Chinese survivors brought suit in international courts. The weight of decades fell into the open air.

Governments reacted unevenly. In 1993, Japan issued the Kono statement acknowledging military involvement in establishing and running comfort stations. Yet the language was careful, hedged, subject to denial by later administrations. Monetary settlements like the Asian Women’s Fund in 1995 were offered as atonement money, but many survivors rejected them, demanding legal responsibility rather than charity.

The paradox repeated itself, recognition without full acceptance, apology without closure. The memory wars grew bitter. Nationalists in Japan dismissed testimonies as fabrications, while in Seoul and Manila, civic groups built statues and memorials. In 2011, a bronze girl in Hanbok was placed opposite the Japanese embassy in Seoul.

Her empty chair beside her, waiting for absent witnesses. Every Wednesday since, protesters have gathered there, demanding justice for those whose voices were ignored in 1946. For the survivors themselves, memory carried a double edge. Speaking meant reliving, yet silence meant erasia. Some gave testimony once, then retreated into privacy.

Others traveled the world, determined that their last years would not be lived in shadows. One Filipina survivor, Lola Rosa, told an audience in 1996, “We are not just history. We are still here. We still breathe, and we want the world to know.” The trials had passed them by, but memory, once unlocked, would not fade again. What had been hidden in huts and ledgers became a matter of public conscience? But this was only the prelude to the broader question.

How would nations and history itself choose to remember? By the end of the 20th century, what had once been whispered in corners became inscribed on stone, bronze, and paper. The comfort women system was no longer a forgotten footnote. It had become a contested memory shaping the relationships of nations. Monuments rose in Seoul, Manila, San Francisco, and Berlin. In each the figure of a young woman sat in silence, her gaze steady, her chair beside her empty, a demand for remembrance, not pity.

Yet every statue drew protest notes from Tokyo, where officials insisted the past had been addressed, the apologies sufficient, the ledger closed. This was the paradox carried into the future. The survivors had been silenced for decades, only to be disbelieved when they finally spoke. Governments argued over treaties and settlements, while the women insisted on something simpler and deeper.

Acknowledgement. Numbers mattered. Whether it was the 50,000 estimated by conservative scholars or the 200,000 cited by activists, but the essential truth lay not in statistics, but in individual voices. Each testimony chipped away at the myth that the past could be buried. And yet another contrast persisted.

Many Americans who encountered survivors in 1945 carried memories not of conquest but of restraint. One army doctor years later described the paradox in his diary. We had been taught that the Japanese used these women like rations, expendable and replaceable. To us, they were simply human beings in need of care. I could not bring myself to touch them as they feared we would.

It was a small remembrance, but one that echoed the larger theme. Sometimes mercy could subvert even the momentum of war. From huts to hospitals, from tribunals to statues, the story unfolded across scales. It began with bamboo screens trembling in the night and ended with diplomatic cables exchanged in capital cities.

The women who once flinched at the Yaoong sound of boots lived long enough to see their names etched on plaques. Their testimonies archived, their dignity fought for on the streets of foreign cities. They had come as captives, their identities stripped into numbers. They lived to see themselves restored as witnesses. They had been told no one would care. Yet decades later, students studied their words, journalists wrote their names, and strangers wept before their statues.

In a war remembered for bombs and battleships, the enduring weapon was not destruction, but testimony. They had come as conquerors, one historian wrote of the Japanese army. But they left as students, their empire dismantled, their myths exposed. and the Americans, whose silence and distance so shocked the survivors in 1945, left behind not claims of ownership, but a paradoxical memory. That in the midst of total war, restraint could carry its own power.

In the end, America’s greatest weapon was not its bombs, but its abundance, the ability to offer soap instead of chains, peaches instead of orders, silence instead of command. For the women who endured the darkest machinery of the war, those small mercies were proof that even after years of systematic cruelty, humanity had not been entirely extinguished.

The story of the Japanese comfort girls and their encounter with American soldiers is not one of simple villains and saviors. It is a narrative of paradox, of a system that reduced women to ledgers, and of strangers who offered them back fragments of dignity. It is the story of silence broken decades too late, of memory weaponized by politics, of survivors who demanded to be seen as more than history.

Above all, it is a reminder that even in the most brutal landscapes of war, the smallest acts of humanity, a gift of food, a refusal to exploit, the recognition of a name, can echo longer than the thunder of guns.