Mxc-Japanese POW Women — In Tears When American Soldiers Protected Them From Their Own Commanders

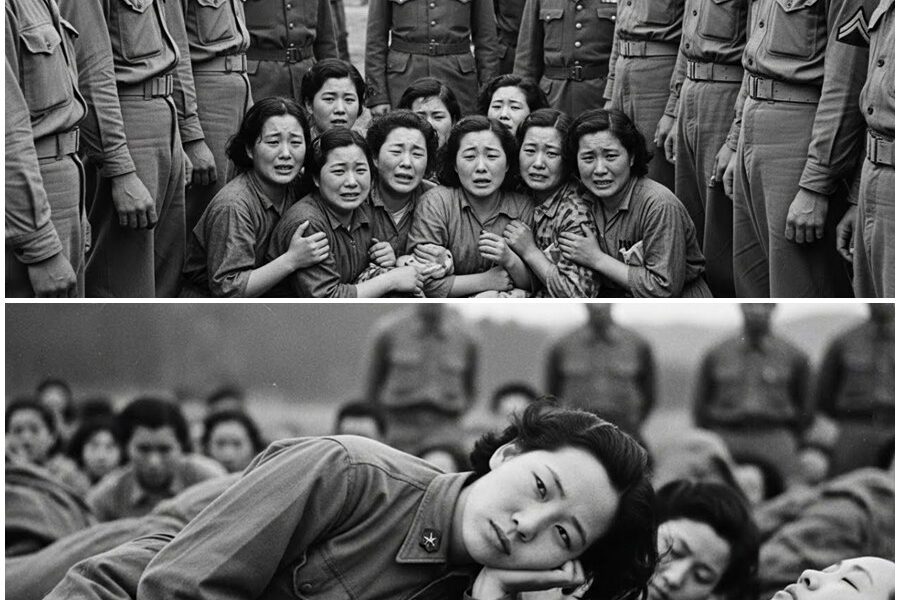

They were told that capture meant dishonor worse than death. But when 300 Japanese women stepped off crowded transport trucks at Camp Lordsburg, New Mexico in August 1945, they expected American soldiers to laugh at their shame and Japanese officers to command their silence. Instead, something impossible happened.

When their own commanders raised their fists to enforce obedience, American guards stepped between them. The women wept, not from pain, but from confusion. For the first time in their lives, the enemy became their protectors. and nothing in their training had prepared them for that.

The summer heat of New Mexico hit them like a wall. After weeks on a transport ship from the Pacific, then days on a cramped train, the women finally arrived at a camp surrounded by desert. The landscape looked like another planet, flat, brown, endless.

Mountains rose in the distance like jagged teeth against a burning sky. There were no trees, no green fields, just dust and rocks and the smell of hot metal from the train tracks. The women wore simple cotton uniforms, some torn from the journey. Their hair was tied back in tight buns, faces sunburned and stre with sweat.

Most were young, between 18 and 30, though a few older women stood among them. They had been nurses, clerks, radio operators, and translators working for the Japanese military across the Pacific Islands. When the war ended suddenly in August, they found themselves prisoners, not heroes.

As the trucks rolled through the camp gates, barbed wire glinted in the sun. Guard towers stood at each corner and long wooden barracks stretched in neat rows. American soldiers watched them arrive, rifles resting on their shoulders. Some looked curious, others looked bored. None looked cruel, which confused the women more than anything. The dust tasted bitter on their tongues.

The air smelled different here, dry, clean, without the humidity of the Pacific Islands, or the smoke of war. As they climbed down from the trucks, their legs wobbled. Some had to hold on to each other to stay upright. The ground beneath their feet felt strange and solid after weeks at sea. American voices rang out, giving orders in English.

The sounds were harsh and unfamiliar. A few women understood some English, but most heard only noise. They stood in tight groups, shouldertoshoulder, drawing comfort from being close. Then they saw them, the Japanese officers. Six men stood near a separate building, also prisoners, but wearing what remained of their uniforms with stiff pride.

The women’s hearts sank. Even here, even in captivity, the hierarchy remained. The commander’s faces were hard as stone. One of them, a lieutenant with a thick mustache, scanned the women with cold eyes. The women knew that look. It meant obedience. It meant silence. It meant shame if they failed.

Ko, a 24-year-old who had worked as a translator in Manila, felt her throat tighten. She whispered to the woman next to her, “They are here. The commanders are watching us.” “Then we must not bring dishonor,” the other woman replied, her voice barely audible. Around them, whispers spread like wind through grass. Stand straight. Do not cry. Remember who we are. They had been taught since childhood that capture was the ultimate shame.

A true Japanese soldier, they were told, died before surrendering. But the war ended so suddenly, the emperor himself had spoken of peace. And now they were here, alive, but dishonored. An American officer approached, holding a clipboard. He was young, maybe 30, with kind eyes and a tired face. He spoke slowly using simple words.

A Japanese American translator stood beside him, repeating everything in their language. You will be safe here. You will be fed and given shelter. You will be treated according to international law. Safe? The word felt foreign. They had been told Americans were demons who showed no mercy. Yet here was this man speaking gently, promising safety.

But then the Japanese lieutenant stepped forward, his voice cut through the air like a blade. You will maintain discipline. You will obey. You will not embarrass our nation further. The women’s heads dropped immediately. Yes, they understood. They were prisoners, but they were still Japanese. They still had to obey.

Even if everything else had fallen apart, that remained. The American guards directed the women toward a large building. Inside, it was cooler with fans spinning on the ceiling. The women were told to line up. One by one, they would be checked by doctors, given clean clothes, and assigned to barracks. Ko’s heart pounded.

She had heard stories, terrible stories, about what happened to captured women. The propaganda had been clear. Americans would humiliate them, hurt them, use them. She clenched her fists, trying to stay calm. When her turn came, she entered a small room. An American nurse stood there. A woman with red hair and freckles. She smiled. Ko froze.

Why was she smiling? Through the translator, the nurse spoke. I’m going to check your health. Just basic things. Temperature, weight, any injuries. Is that okay? Is that okay? No one had ever asked Ko if something was okay. In the Japanese military system, you obeyed. You didn’t get asked.” She nodded, unsure what else to do. The nurse was gentle. She checked Ko’s pulse, looked at her eyes, asked if she had any pain.

When she noticed old bruises on Ko’s arms, marks from when a commander had grabbed her roughly for a mistake in translation, the nurse’s smile faded. “Did someone hurt you?” she asked through the translator. Ko said nothing. “How could she explain? In her world, that was just discipline. That was normal.

The nurse wrote something on her chart, then handed Ko a bundle of clothes, a simple dress, undergarments, and a pair of shoes. These are for you. You can change in the next room. Take your time. Take your time. Another strange phrase. Ko had never been told to take her time. She had only been told to hurry, to be efficient, to never waste a moment.

Outside, the other women went through similar experiences. Most were silent, moving like robots, doing exactly what they were told. But inside, confusion swirled. The Americans were not cruel. They were not rough. They asked questions instead of giving orders. It made no sense. After processing, the women were led to a dining hall. Long tables filled the room, and the smell of food, real food, hit them immediately.

For months, they had eaten rice mixed with weeds, thin soup, sometimes fish if they were lucky. They had watched their portions shrink as supply lines broke down. Many had lost weight, their uniforms hanging loose on thin frames. Now they saw tables covered with trays. There was rice, yes, but also vegetables, meat, bread, and fruit.

Apples sat in bowls, shining red. Pictures of water, and milk stood at each table. The sight was overwhelming. An American cook, a large man with a friendly face, gestured for them to take plates. Help yourselves. Eat as much as you want. The women looked at each other, uncertain.

Was this a test? Were they supposed to refuse to show discipline, or were they really allowed to eat? Slowly, one woman stepped forward, then another. Soon they formed a line, taking plates with trembling hands. When Ko received her tray, heavy with food, she nearly dropped it. The weight alone shocked her. This was more than she had eaten in a week back on the islands.

They sat in silence as they had been trained to do. No talking during meals, no wasting food, no showing emotion. Ko picked up her fork. They had been given real utensils, not just chopsticks or fingers, and took a small bite of the meat. It was warm, seasoned, tender. Her eyes watered around her. Other women reacted the same way. Some cried quietly into their food.

Others ate mechanically as if afraid the plates would be taken away. One older woman who had been a nurse whispered a prayer of thanks under her breath. But then came footsteps, heavy boots on wood floors. The Japanese officers entered the dining hall. The women immediately stiffened, forks paused midair, heads bowed lower.

The lieutenant with the mustache walked between the tables, his face a mask of disgust. He spoke in harsh Japanese. You eat their food and forget your honor. You accept comfort from the enemy? Have you no shame? The room fell completely silent. Several women set down their forks. Their appetites vanished. Guilt crashed over them like a wave. He was right, wasn’t he? They were eating enemy food.

They were accepting kindness from Americans. They were prisoners, disgraced, and now they were betraying their country further by not resisting. Ko felt tears slide down her cheeks, not from joy at the food, but from shame. Her throat tightened. She couldn’t swallow. That night, the women were taken to their barracks, long wooden buildings with rows of beds.

Each bed had a mattress, a pillow, and two blankets. After sleeping on hard ground, on crowded ships, on anything they could find, the sight of real beds felt like a dream. But the Japanese officers were housed in a nearby building, and their voices carried in the desert night. The women lay in their beds, exhausted, but unable to sleep.

Through the thin walls, they heard the commanders arguing among themselves, discussing the disgrace of surrender, the weakness of accepting American charity. One voice rose above the others. the lieutenant. Tomorrow we will make sure they understand. They may be prisoners, but they are still Japanese.

They will maintain honor, or they will be reminded of their duty. The threat hung in the air. The women knew what reminded meant. It meant punishment. It meant being pulled aside and scolded, or worse. Even in captivity, the hierarchy held. The commanders still had power over them, not through official authority, but through culture, through shame, through the weight of everything they had been taught since birth.

Ko stared at the ceiling, watching shadows from the guard tower lights move across the wooden beams. Her stomach was full for the first time in months. She was clean. They had been allowed to shower with real soap and warm water. She was lying on a soft bed. And yet, she had never felt more conflicted.

“Are you awake?” whispered the woman in the next bed. Her name was Yuki, a former clerk from Tokyo. “Yes,” Ko whispered back. “Do you think we are betraying our country by being here?” Ko didn’t answer right away. How could she? Everything she believed was being challenged. The Americans were supposed to be monsters, but they had been kind.

The commanders were supposed to protect them, but they made them feel ashamed for surviving. I don’t know, Ko finally said. I don’t know anything anymore. Yuki was quiet for a moment, then she said. The nurse gave me medicine today for an infection I’ve had for weeks. No one in our unit had medicine to give me, but the enemy did.

The simple truth of that statement settled over them both. The enemy had medicine. The enemy had food. The enemy had asked if they were okay, and their own commanders only offered shame. Outside, the desert wind whispered against the barracks. Somewhere in the distance, a coyote howled. The women lay awake, caught between two worlds.

The one they had known, where obedience and honor were everything, and this new one, where the enemy showed unexpected mercy. Neither world made sense anymore. The days began to follow a rhythm. Every morning at 6:00 a.m., a bell rang. The women woke, made their beds with military precision, and lined up outside the barracks.

An American guard would do a quick count, then lead them to the dining hall for breakfast. Breakfast was always generous. Oatmeal or rice, toast with butter, coffee or tea, sometimes eggs and bacon. The women slowly got used to eating real meals. Their bodies responded. After weeks of being weak and tired, they started to feel stronger. Their skin cleared.

Their hair, which had been dull and breaking, began to shine again. After breakfast, they were given work assignments. The Americans needed help with various tasks around the camp. Laundry, kitchen work, sewing and mending uniforms, helping in the infirmary. The work was not hard. No one yelled at them. No one hit them for small mistakes. The American supervisors spoke firmly but fairly.

If someone didn’t understand, they would explain again slowly. Ko was assigned to help in the infirmary because of her English skills. She worked alongside American nurses, translating when other Japanese prisoners needed medical care. She watched how the nurses treated patients gently with respect, explaining what they were doing before they did it.

This was so different from the military hospital where she had worked, where patients were expected to endure in silence. The women were paid for their work. Not much, just camp currency that could be used at the canteen. But it was something. They could buy small things like soap, combs, writing paper, even candy.

The first time Ko held a chocolate bar, she stared at it for a long time before eating it. Chocolate had been a luxury in Japan even before the war. Now the enemy was selling it to her. In the afternoons after work, they had free time. Some women gathered in small groups to talk quietly. Others wrote letters home, though they didn’t know if the letters would ever reach Japan.

A few attended English classes that the camp offered. The Americans seem to believe that keeping the prisoners busy and educated was important. Evenings brought dinner, then more free time before lights out at 9:00 p.m. The routine was simple, predictable, almost peaceful, and that made the guilt worse.

Because while the women ate three meals a day and slept in beds with clean sheets, they knew what was happening back home. They knew Japan had been bombed, cities destroyed, families scattered, food was scarce, children were starving, and here they were, prisoners of war, living better than they had lived in years. Letters began arriving from Japan, delivered through the Red Cross.

The words were carefully censored, but the meaning was clear. Yuki received a letter from her mother. We are grateful you are alive. Do not worry about us. We manage with what we have. But between the lines, Yuki could read the truth. They were not managing. They were suffering.

Another woman, Hana, received news that her brother had died in the final months of the war. She sat on her bed holding the letter, tears falling silently around her. Other women cried too for their own losses, for the weight of survival, while others had died. The Japanese commanders noticed the letters. They noticed the women gaining weight, looking healthier, and they did not approve.

One afternoon, as the women returned from work, the lieutenant gathered them in the yard. American guards watched from a distance, but didn’t interfere. The commanders were prisoners, too, and they had the right to speak to their country women. The lieutenant’s voice was cold and sharp. Look at yourselves. You grow fat on enemy food while your families starve.

You smile at American soldiers while our brothers lie dead in the Pacific. You have forgotten who you are. The words cut deep. The women stood frozen, heads bowed, unable to defend themselves because part of what he said felt true. They were eating well. They were accepting kindness from the enemy, and every moment of comfort felt like a betrayal.

“You will remember your place,” the lieutenant continued. “You will stop fraternizing with the Americans. You will maintain dignity and discipline, or I will ensure you understand the meaning of shame.” After he dismissed them, the women walked to their barracks in silence. The joy they had started to feel, the small happiness of being safe and fed, evaporated.

They were back in the familiar cage of obligation and honor, even if the bars were invisible. But the Americans noticed the change. Sergeant Miller, who supervised the kitchen, saw how quiet the women had become after the commander’s speech. He saw the fear in their eyes when they passed the Japanese officers. He saw tears being quickly wiped away. One day, he approached Ko as she worked in the infirmary.

“Is everything okay?” he asked. “You seem different. Scared.” Ko didn’t know how to answer. How could she explain the complex web of honor, shame, duty, and fear that governed her life? How could she make him understand that her own people were more frightening than her capttors? “It’s nothing,” she said quietly.

But Sergeant Miller wasn’t fooled. He had been in the military long enough to recognize fear, and he didn’t like seeing it in someone who should have been safe under his watch. Other American soldiers noticed, too. Private Johnson, who worked in the laundry, saw how the women flinched when the Japanese officers walked by.

He saw how they stopped laughing or talking the moment a commander appeared. He mentioned it to his sergeant. “Something’s not right,” he said. “Those women are afraid of their own guys.” The sergeant nodded. “I’ve seen it, too. Keep an eye out. If anything happens, we need to know.” Meanwhile, small kindnesses continued.

An American cook named Betty started saving extra fruit for the women. She noticed they never took as much as they were allowed, so she would slip apples or oranges into their hands with a wink. For later, she’d say, “A guard named Thompson taught a few women how to play cards during their free time. They giggled at the strange game, trying to understand the rules.

For brief moments, they forgot about everything else and just enjoyed being young women playing a game. These moments of connection confused the women even more. The Americans treated them like human beings. They joked with them, helped them, showed patience when they made mistakes. The kindness was steady and genuine, not a trick or a test.

But every time they started to relax, to feel safe, the commander’s voices would echo in their minds. You are disgracing your nation. You have forgotten your honor. The women were caught between two worlds. One offered food, safety, and kindness, but came from the enemy.

The other offered familiar authority and cultural identity, but came with harsh judgment and shame. They didn’t know which world they belonged to anymore. Ko lay awake many nights thinking about this. She remembered her mother’s words before she left for military service. Serve with honor. Never bring shame to our family.

But what was honor now? Was it refusing food from the enemy and starving? Was it rejecting kindness because it came from the wrong people? Or was honor simply surviving, living to see her family again? She didn’t have answers. None of them did. They were living in a gray area that no one had taught them how to navigate. The war had clear sides. Japan versus America, right versus wrong.

But captivity blurred everything. Here the enemy fed you. Here your own countrymen made you feel worthless. Here nothing was simple anymore. And the tension was building. Everyone could feel it. The commanders were getting angrier. The women were getting more confused. And the Americans were starting to watch more carefully, sensing that something was about to break.

Ko kept a small notebook hidden under her mattress. At night, when everyone else was asleep, she would write by the dim light that came through the windows from the guard towers. She wrote in Japanese, careful to keep her thoughts private. One entry read, “I don’t know who I am anymore. For 24 years, I knew exactly who I was. A Japanese woman, obedient daughter, faithful servant of the emperor.

Now I am a prisoner. The enemy treats me better than my own commanders do. They ask me if I’m okay. They give me medicine when I’m sick. They pay me for my work. And I feel guilty for being grateful. Is that wrong? Am I betraying my country by accepting kindness?” Another entry. A week later.

Today, Sergeant Miller asked me about my family. He wanted to know if I had brothers or sisters. When I told him about my younger sister, he showed me a picture of his own sister back in America. He misses her. He worries about her. In that moment, I saw him not as an enemy soldier, but as a brother. And I realized he probably sees me as someone’s sister, too.

Not as an enemy, just as a person. This thought terrifies me because it changes everything. She was not alone in her confusion. Late at night, after lights out, whispered conversations filled the barracks. “Do you think we’re wrong to eat their food?” One woman asked, “What choice do we have? Starve to show our loyalty?” Another responded, “But the commanders say we’re betraying our nation.

The commanders wanted us to die rather than surrender. Are they really the ones we should listen to?” This last comment was met with sharp gasps, to question the commanders was unthinkable. But slowly, quietly, the women were starting to think the unthinkable. Yuki voiced what many felt. I’ve been thinking about something.

The Americans didn’t have to feed us so well. They didn’t have to give us real beds or medicine or pay us for our work. The Geneva Convention says prisoners must be treated humanely, but they could do the bare minimum. Instead, they do more. Why? No one had an answer. But the question stayed with them.

The breaking point came on a hot September afternoon. The women were returning from their work assignments, tired, but in good spirits. One of the younger women, a girl named Sakura, who couldn’t have been more than 19, was humming a song, an American song she’d heard on the radio in the kitchen. The Japanese lieutenant appeared from nowhere. His face was red with rage.

He grabbed Sakura by the arm, yanking her out of line. You sing their songs now. You have completely forgotten your honor. Sakura froze, terrified. The lieutenant raised his hand to strike her. But before his hand could fall, an American guard stepped between them. It was Sergeant Miller. His voice was calm but firm. That’s enough. Step back.

The lieutenant’s eyes blazed. This is not your concern. She is Japanese. I am her superior officer. You’re a prisoner same as her, Miller replied, his hand resting on his belt near his sidearm, not threatening, but ready. And in this camp, prisoners don’t hit each other. Step back. For a long moment, nobody moved.

The women held their breath. The other American guards had noticed the confrontation and were approaching. The lieutenant was outnumbered, and he knew it. His hand dropped, but his face twisted with humiliation and rage. He spat words at Sakura in Japanese. You are dead to honor. You are not Japanese anymore. Then he turned and walked away, the other commanders following him.

Sakura stood trembling, tears streaming down her face. But Sergeant Miller knelt down to her level, his voice gentle. Are you okay? Did he hurt you? Through her tears, Sakura shook her head. She wanted to say something to thank him, but no words came. All she could do was cry. Miller looked at Ko, who had witnessed everything. Can you tell her she’s safe? Tell her that won’t happen again.

Ko translated her own voice shaking. When Sakura heard the words, she cried harder, not from fear now, but from overwhelming confusion. The enemy had protected her from her own people. Her own commander had called her dead to honor. But the American, the one she’d been taught to fear, had kept her safe.

That night, the barracks buzzed with whispered conversations. The women couldn’t stop talking about what had happened. For the first time, they spoke openly about their doubts. He was going to hit her, her own commander. and the Americans stopped him. Why would he do that? Why would he care? Because maybe they do see us as human beings.

But we’re the enemy, are we? The war is over. We’re prisoners, not soldiers anymore. The next morning, something had changed. The women walked differently. They held their heads a little higher. When they passed the Japanese commanders, they didn’t bow as deeply as before. The fear was still there, but something else was there, too. A quiet defiance, a small spark of independence.

The Americans noticed. Captain Richards, the camp commander, called Sergeant Miller into his office. The situation with the Japanese officers is getting worse, Richard said. They’re trying to maintain control over the women through intimidation. But this is an American camp.

Those women are under our protection, not under the authority of other prisoners. What do you want me to do, sir? Miller asked. Keep watching. And if any of those officers try to enforce discipline again, intervene. The women need to understand that they’re safe here. Really safe. Not just from us, but from everyone. Miller nodded. Some of them are starting to see it, sir.

But they’ve been trained their whole lives to obey authority, especially male authority. Breaking that conditioning isn’t easy. I know, but we have to try because if we don’t protect them, we’re no better than the propaganda they’ve been fed about us. The women’s transformation was gradual, but real. They started asking questions, small ones at first.

Ko asked Sergeant Miller about America, about what life was like there. Did women work? Could they choose their own husbands? Did they go to school? Miller answered honestly, and his answers opened new worlds. Women in America could vote. They could own property. They could divorce husbands who mistreated them. They could become doctors, lawyers, even pilots.

The war had shown that women could do jobs that everyone said only men could do. This information spread through the barracks like wildfire. The women discussed it endlessly. Some found it shocking. Others found it exciting. All found it thought-provoking.

Imagine, Yuki said one evening, choosing who you marry, not having it arranged by your parents. Imagine, Hana added, learning any profession you want, not just the ones considered appropriate for women. Imagine, Ko said quietly, not being hit for making a mistake or asking a question. They were beginning to imagine different possibilities.

Not necessarily that they wanted to become American, they were still Japanese in their hearts, but that maybe the way they had been taught things must be was not the only way things could be. The commanders sensed this shift and it enraged them. They saw their authority slipping away. They saw the women listening to American ideas. They saw what they considered the corruption of Japanese values.

And they became desperate to reassert control. But they didn’t understand something crucial. The women had been afraid of the commanders only because they believed there was no alternative, that obedience was survival. Now they had seen an alternative. They had seen American guards protect them.

They had seen that life could exist without constant fear and punishment. And once you’ve seen freedom, even a glimpse of it, you can’t pretend you haven’t. The commander’s power was built on fear and shame. But the Americans had offered something stronger. Dignity and choice, and slowly, steadily, dignity was winning.

The confrontation everyone had been dreading came on a cool October morning. The women were lined up for breakfast when the lieutenant and two other commanders approached. The lieutenant carried a stick, a traditional symbol of authority and discipline in the Japanese military. His voice rang out across the yard. You have all forgotten your duty.

You have become soft, accepting the enemy’s charity, smiling at their soldiers, forgetting the honor of Japan. Today, you will be reminded of who you are. He pointed the stick at three women, Sakura, Yuki, and Ko. You three especially have been seen fraternizing with Americans, laughing with them, acting as if you are friends with the enemy. This will be corrected. The women’s blood ran cold.

They knew what corrected meant. Public punishment, humiliation, physical discipline. It had happened before in the military to others who had broken rules or shown weakness. The American guards were at the other end of the yard, but Sergeant Miller saw what was happening. He started walking quickly toward the scene.

The lieutenant raised his stick, stepping towards Sakura. You will kneel and apologize for your dishonor. Sakura’s legs trembled, but she didn’t move. Something in her had changed since the last confrontation. She had been protected once. Maybe she didn’t have to accept punishment for the crime of being treated like a human being. I said kneel, the lieutenant shouted.

No, Sakura whispered, then louder. No. The word hung in the air like thunder. The other women gasped. No one said no to a commander. The lieutenant’s face turned purple with rage. He raised the stick high, preparing to strike. But before it could fall, Sergeant Miller was there along with four other American guards.

Miller grabbed the stick mid- swing, yanking it from the lieutenant’s hands. “I told you once before,” Miller said, his voice dangerously quiet. “You don’t touch these women. Not now. Not ever again. They are Japanese. They are under my authority. The lieutenant screamed, switching to English so the Americans would understand.

Captain Richards approached, having been alerted to the commotion. He addressed the lieutenant directly. You have no authority in this camp. You are a prisoner same as them, and these women are under the protection of the United States military. If you attempt to harm them again, you will be placed in isolation.

Do you understand? The lieutenant looked around. He was surrounded by American guards. The women were watching and for the first time he saw something new in their eyes. Not fear, not submission, but defiance. They weren’t going to obey him anymore. He had lost. “This is a disgrace,” he hissed. “You are all traitors to Japan.

” Ko stepped forward, her voice shaking, but clear. “We are survivors. That is not the same as traders.” The word stunned everyone. a Japanese woman contradicting a male officer in public, in front of everyone. It violated every cultural norm she had been raised with, but she had said it anyway. The lieutenant stared at her with pure hatred. Then he turned and walked away, the other commanders following.

They knew they had lost control. The American protection had broken their power. Captain Richards addressed the women. You don’t have to be afraid of them anymore. You are under our protection. Anyone who tries to harm you will answer to us. You have my word. Through Ko translating with tears streaming down her face, the women heard this promise, and one by one, they began to cry.

Not from fear or shame, but from relief, from gratitude, from the overwhelming realization that they were truly safe. Sakura fell to her knees, sobbing. Yuki covered her face with her hands. Even the older women, who had trained themselves never to show emotion, wept openly. The Americans had done what their own commanders never had. They had protected them.

And in that moment, everything the women had been taught about honor, about loyalty, about who was good and who was evil shattered completely. The enemy had become their protectors, and their protectors had revealed themselves as the true source of their fear. In the weeks after the confrontation, life in the camp changed dramatically. The Japanese commanders were moved to a separate section of the camp far from the women.

They were no longer allowed to interact without American supervision. The women felt like a weight had been lifted from their shoulders. But a new anxiety crept in. Rumors began to spread that prisoners would soon be sent back to Japan. The war was over. Peace treaties were being signed. Eventually, everyone would go home. Home. The word felt strange.

What was home now? Japan had been bombed, cities destroyed, millions dead. The country they left was gone, replaced by something broken and occupied. And the women themselves had changed. They had seen a different way of life. They had experienced protection instead of punishment, kindness instead of cruelty.

What will happen to us when we go back? Yuki asked one evening as the women gathered in the barracks. We’ll be seen as shameful, another woman said. Prisoners who survived in Japan, we should have died rather than be captured. But the emperor himself told us to surrender, Ko pointed out. He said the war was over. We were following his command.

Do you think our families will see it that way? Do you think our communities will forgive us for living while others died? No one had answers. The fear of returning was real. They would be going back to a country that might reject them, to families that might be ashamed of them, to a society that valued death in battle over survival in captivity.

Some women whispered that they wish they could stay in America. It was a treasonous thought, but they couldn’t help feeling it. Here they were safe. Here they were treated with respect. Here they had started to imagine different futures for themselves. In December 1945, the first group of women was scheduled to leave.

Ships would take them from California back across the Pacific to Japan. The women packed their few belongings, some clothes, letters from home, small gifts that American soldiers had given them. Sergeant Miller came to say goodbye to the women he had worked with. He found Ko in the infirmary organizing supplies. I wanted to give you something, he said, handing her a book.

It was a small English dictionary. So, you can keep learning. Maybe it will help you in the future. Ko took the book, holding it like treasure. Thank you, Sergeant Miller, for everything, not just the book. for protecting us, for showing us that enemies can be kind. Miller smiled sadly. I hope things go well for you back home. I hope you find peace. I don’t know what we’ll find, Ko admitted. But we’re different now.

We’ve seen things that can’t be unseen. We’ve learned things that can’t be unlearned. Sometimes that’s the best thing that can come from war, Miller said. Learning that the enemy is human, too. Remembering that kindness matters more than national boundaries. Similar conversations happened all over the camp.

American soldiers who had worked with the women came to say goodbye, to wish them well, to give them small tokens, photographs, books, chocolates for the journey. The women were overwhelmed by these gestures. They had arrived expecting cruelty and were leaving as friends.

The Japanese commanders, being shipped separately, watched with disgust as the women laughed and cried with American soldiers. But the women no longer cared what the commanders thought. They had learned a crucial lesson. That honor wasn’t about blind obedience or dying for a cause. Honor was about treating people with dignity, about protecting the vulnerable, about choosing kindness over cruelty. The Americans had taught them that.

The enemy had taught them honor. Decades later, an elderly Ko sat in her home in Tokyo surrounded by her grandchildren. They asked her, as they often did, to tell stories about the war. “Most of her stories were sad, about the fear, the hunger, the loss. But this one was different.

There was a time when I was a prisoner in America,” she began, and the children leaned in, eyes wide. I thought it would be the worst time of my life. I had been taught that Americans were cruel, that capture meant dishonor and suffering. But I learned something surprising. All I learned that sometimes the enemy shows you more kindness than your own people do. She told them about Sergeant Miller stepping between her and the commander.

About the American nurses who treated her injuries, about the food, the safety, the protection, about the moment she realized that everything she had been taught was wrong. It changed how I see the world. She said, “I learned that no group of people is entirely good or entirely evil. That kindness can come from unexpected places.

That true honor isn’t about following orders blindly. It’s about treating others with dignity and standing up for what’s right, even when it’s hard.” Her grandchildren listened, absorbing these words. “This was not the usual war story. This was something more complicated, more human, more true.” “Did you ever see Sergeant Miller again?” one grandchild asked. Ko shook her head.

“No, but I never forgot him. and I tried to live my life the way he showed me with kindness, with protection for those who need it, with courage to stand against cruelty, even when it comes from people who are supposed to be on your side.” She picked up the old English dictionary from her shelf, worn from decades of use.

He gave me this, and through it, he gave me a new way of seeing the world. That was the greatest gift anyone has ever given me. And so, the soap became symbols, the meals became memories, and the protection became proof that humanity can survive even in the machinery of war. For those 300 Japanese women, the experience of captivity in America became not a story of shame, but a story of transformation.

They learned that enemies could show mercy. They learned that true strength sometimes means protecting others rather than dominating them. They learned that honor isn’t about dying for a cause. It’s about living with dignity and helping others do the same.

The tears they shed when American soldiers stepped between them and their own commanders were tears of revelation. In that moment, everything they thought they knew about the world shattered and was rebuilt into something more complex, more human, more true. As Ko told her grandchildren years later, “Sometimes kindness comes from the most unexpected places. And when it does, it changes you forever.

It teaches you that the world is not divided into pure good and pure evil, but into those who choose compassion and those who choose cruelty.” And that choice has nothing to do with which uniform you wear or which flag you salute. That is the story worth remembering. Not just the battles and the bombs, but the small moments of humanity that survived despite the war.

The moments when people chose protection over punishment, kindness over cruelty, dignity over shame. If this story moved you, please subscribe to our channel and hit the like button. These untold stories from World War II deserve to be remembered and shared. History is not just about the famous battles. It’s about the human moments that changed lives forever. Thank you for watching.