When planning the Ardennes counteroffensive in late 1944, German leader Adolf Hitler believed it was essential to seize at least one intact bridge over the Meuse River. His aim was to divide the Allied forces, cross the river, and advance toward Antwerp. Speed was crucial — any delay would allow Allied troops to regroup and block the German advance. To achieve this goal, Hitler assigned a special mission, Operation Greif, to Lieutenant Colonel Otto Skorzeny, a well-known commando leader.

Planning the Mission

In October 1944, Hitler personally briefed Skorzeny on the plan. The mission required forming and training a unit that would move ahead with the 6th Panzer Army — the main force of the northern offensive. Their objectives included capturing at least one bridge over the Meuse and disrupting Allied operations through sabotage and misinformation.

Skorzeny’s forces were to use deception tactics, including operating in U.S. uniforms and vehicles. Hitler justified this by noting that similar tactics had been used earlier in the war, explaining that wearing enemy uniforms was only illegal if combat was conducted in disguise.

Despite promises of full support, resources for Operation Greif were limited. Skorzeny’s unit, Panzerbrigade 150, received only a small number of captured American vehicles and one Sherman tank. To compensate, German tanks were repainted and marked to resemble American ones.

Formation of the “Stielau Unit”

To find English-speaking soldiers, Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel circulated a request throughout the German army — but this led to a major security leak, alerting Allied intelligence to the plan. Of the 2,000 volunteers, only a handful spoke English fluently. Skorzeny organized the best into the Stielau Unit, a small reconnaissance and sabotage force equipped with jeeps, radios, and explosives. With just six weeks to prepare, their training remained basic.

Rumors spread that the commandos’ mission included the assassination of Allied leaders such as General Dwight D. Eisenhower. Though untrue, the rumor reached Allied intelligence, causing Eisenhower and other senior commanders to limit their movements — an unintended success for the German deception effort.

Behind Allied Lines

When the Ardennes Offensive began on December 16, 1944, reports of German soldiers disguised as Americans quickly circulated among U.S. troops. The number of infiltrators was exaggerated, but enough were captured to make the threat seem real. These fears disrupted communications and caused confusion within the Allied lines.

Some commandos successfully misdirected U.S. units and interfered with communication lines. Although their overall impact was limited, their presence contributed to uncertainty during the opening days of the Battle of the Bulge.

Capture and Trial of the Commandos

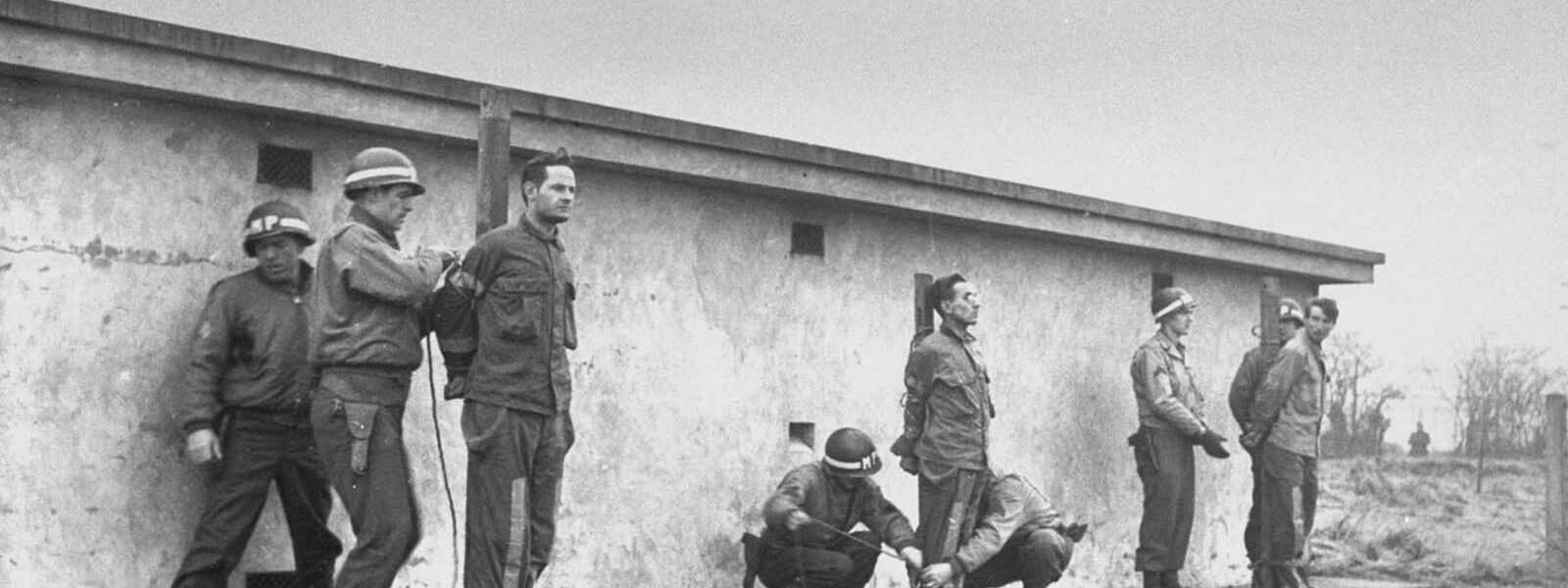

As the German advance stalled, Skorzeny’s disguised forces were ordered to fight as a regular unit. Many were killed or captured. On December 18, 1944, U.S. forces detained three members of the Stielau Unit — Günther Billing, Wilhelm Schmidt, and Manfred Pernass — in Belgium. A military tribunal found them guilty of violating the laws of war for wearing U.S. uniforms and gathering intelligence in disguise. They were executed on December 23, 1944, after review and approval by the U.S. First Army command.

Skorzeny’s Trial After the War

After Germany’s surrender, Otto Skorzeny surrendered to Allied forces and was later tried at the Dachau military court in 1947. He admitted organizing Operation Greif but defended his actions as consistent with wartime law, arguing that his soldiers had removed their disguises before entering combat. His defense was supported by Wing Commander Forest Yeo-Thomas, a British agent who had used similar methods to escape captivity.

The court ruled that wearing an enemy uniform was only a crime if combat occurred while disguised. Skorzeny was acquitted but remained in custody until mid-1948, awaiting denazification review. He later escaped from prison with the help of former comrades.

Later Life and Legacy

In the following years, Skorzeny lived in Spain and reportedly worked as a military advisor in Egypt and Argentina. He was occasionally linked to intelligence activities during the Cold War, though details remain uncertain.

He passed away in 1975 in Madrid. Opinions about him remain divided — some view him as a skilled tactician and pioneer of commando operations, while others remember him for his role in serving the Nazi regime. Operation Greif remains one of the most striking examples of military deception during World War II.