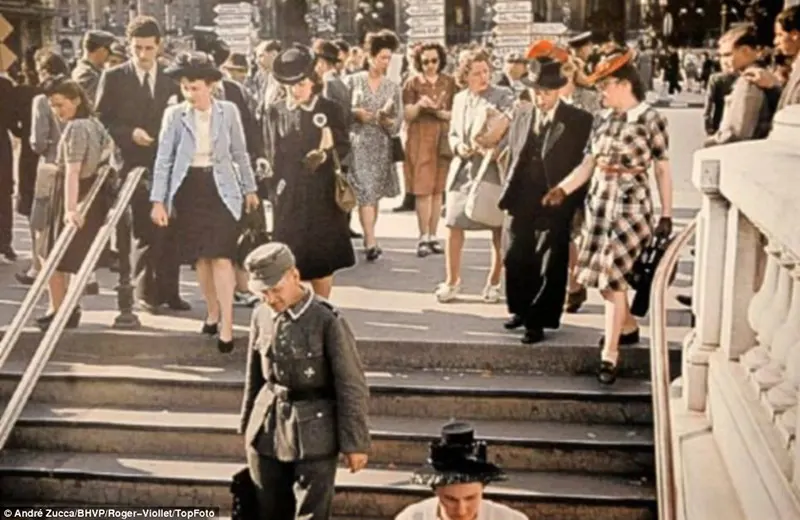

The footage shows fashionably dressed young women and commuters mingling with German soldiers on the busy streets of Paris. The famous streets of the French capital are decorated with symbols of the German regime, but the Parisians appear jubilant.

André Zucca was born in Paris in 1897, the son of an Italian tailor. Zucca spent part of his youth in the United States before returning to France in 1915.

After the outbreak of World War I, he joined the French Army, where he was wounded and awarded the Cross of War. After the war, he began a career as a photographer.

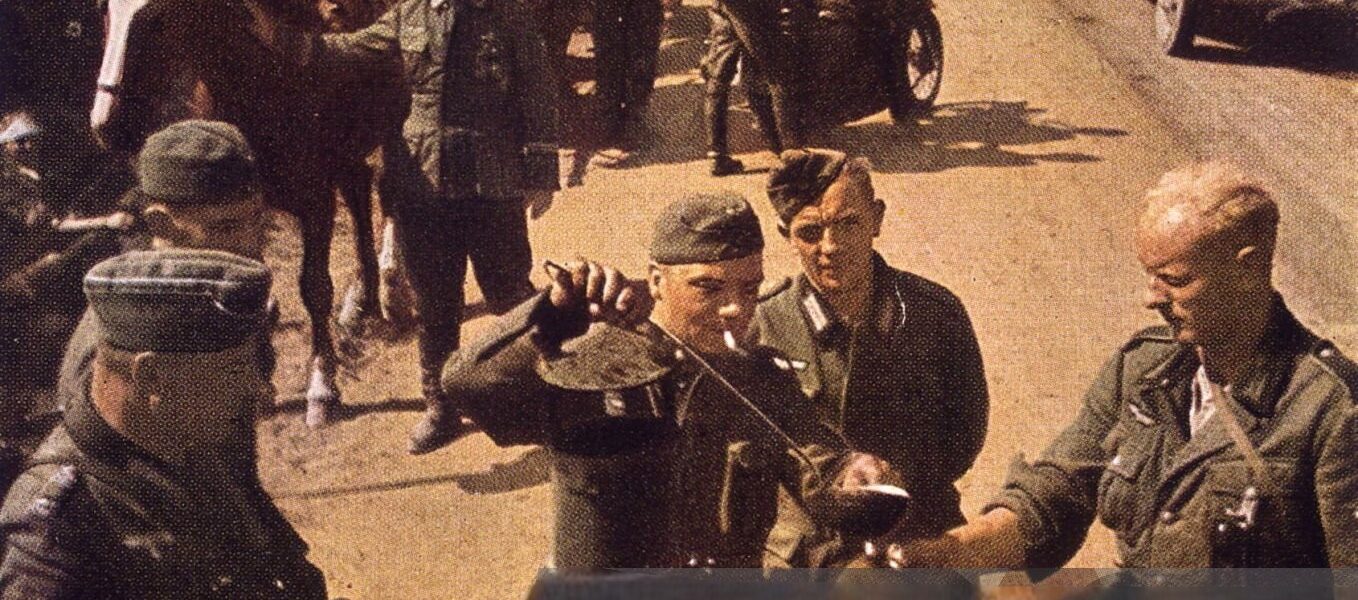

In 1941, he was hired by the German occupiers as a photographer and correspondent for the magazine “Signal,” a propaganda organ of the German Wehrmacht.

His photographs served to convey a positive image of the German occupation in France and to encourage French men to volunteer to join the Legion of French Volunteers Against Bolshevism, a French collaborationist militia on the Eastern Front.

It is disputed whether Zucca’s work for the Germans was connected to ideological sympathies for National Socialism. Some claim he was a right-wing anarchist.

.jpg)

A crowd surrounds a traveling band playing music on a Paris street.

In addition to his contributions to Signal, he was one of the few photographers in occupied Europe who, thanks to his close relationship with the Germans, had access to Agfacolor film, a rare and expensive color film at the time. Today he is best known for his color photographs of everyday life in Paris under German occupation.

After the liberation, he was tried by the French provisional government in October 1944 as part of a legal purge and his journalistic privileges were permanently withdrawn.

The court decided that no further legal action should be taken against Zucca, largely based on the credentials of a resistance fighter who had spoken out on his behalf.

With his journalistic career in ruins, Zucca adopted the name André Piernic and settled in the French commune of Dreux, where he opened a small photography boutique and took wedding and communion photos. He died in 1973.

His photographic collection was purchased by the Bibliothèque historique de la ville de Paris in 1986 and consisted mainly of his photographs of occupied Paris taken during the Second World War.

.jpg)

Women in military uniforms view a war memorial commemorating those who died in the First World War just over two decades ago.

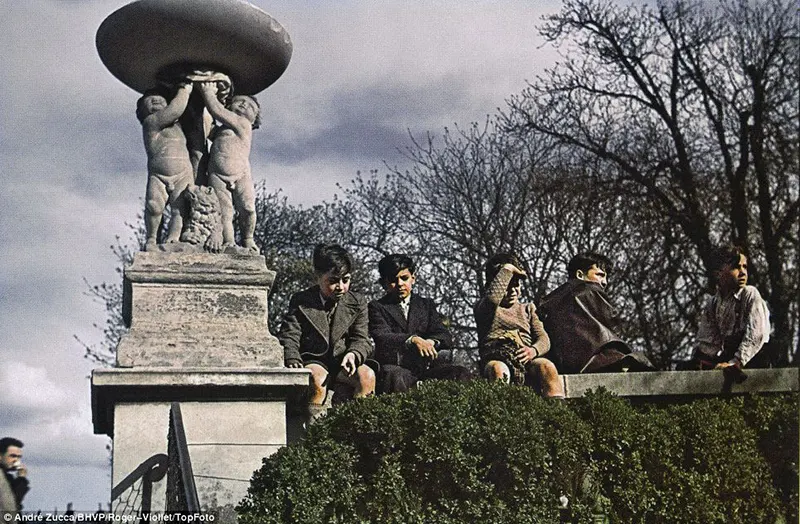

During the occupation, the French government moved to Vichy and Paris was ruled by the German military and French officials recognized by the Germans.

For Parisians, the occupation brought with it a series of frustrations, shortages, and humiliations. A curfew was in place from 9 p.m. to 5 a.m., and the city was dark at night.

Starting in September 1940, food, tobacco, coal, and clothing were rationed. From year to year, supplies became scarcer and prices higher.

One million Parisians left the city and went to the provinces, where there was more food and fewer Germans. Only German propaganda was broadcast in the French press and on the radio.

Parisians’ attitudes toward the occupiers varied widely. Some saw the Germans as an easy source of money, while others, as Roger Langeron, the Prefect of the Seine who was arrested on June 23, 1940, commented, “viewed them as if they were invisible or transparent.”

The attitude of the members of the French Communist Party was more complicated; the party had long condemned Nazism and fascism, but had to change its course after the signing of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact on August 23, 1939.

.jpg)

Two women in military uniforms shop at a toy stall.

Finding food soon became the primary concern of Parisians. The German occupation authorities transformed French industry and agriculture into a machine serving Germany.

Deliveries to Germany had the highest priority; the rest went to Paris and the rest of France. All trucks manufactured at the Citroën plant went directly to Germany. The majority of deliveries of meat, wheat, dairy products, and other agricultural products also went to Germany.

The rationing system also affected clothing: leather was reserved exclusively for German army boots and disappeared completely from the market. Leather shoes were replaced by shoes made of rubber or canvas (bast) with wooden soles.

Numerous substitute products appeared that were not exactly what they were called: substitute wine, substitute coffee (made from chicory), substitute tobacco and substitute soap.

.jpg)

A wealthy-looking man and a woman ride in a cart pulled by two slender Parisians on a tandem.

The search for coal for heating in winter was another concern. The Germans had transferred control of the coal mines of northern France from Paris to their military headquarters in Brussels.

The coal that arrived in Paris was primarily used for factory use. Even with ration cards, it was almost impossible to find enough coal for heating. Supplies for normal heating needs were not restored until 1949.

Although Parisian restaurants were open, they struggled with strict regulations and shortages. Meat could only be served on certain days, and certain products like cream, coffee, and fresh produce were extremely scarce. Nevertheless, the restaurants found ways to serve their regular customers.

The historian René Héron de Villefosse, who lived in Paris during the war, described his experiences: ” The large restaurants, under the strict supervision of frequent checks, were only allowed to serve pasta with water, turnips and beetroot in return for a certain number of admission tickets, but the hunt for a good meal continued for many gourmets .”

For five hundred francs, you could score a good pork chop, hidden under cabbage and served without the required tickets, along with a liter of Beaujolais and a real coffee; sometimes it was on the first floor in the Rue Dauphine, where you could listen to the BBC while sitting next to Picasso.”

.jpg)

There are guards in front of a building, with a sign indicating that it is an important location for the German occupying army.

Many Parisians collaborated with Marshal Pétain’s government and with the Germans, supporting them in municipal administration, the police, and other government functions. French government officials had the choice of collaborating or losing their jobs. On September 2, 1941, all Parisian judges were ordered to swear an oath of loyalty to Marshal Pétain.

Only one, Paul Didier, refused. Unlike the territory of Vichy France ruled by Marshal Pétain and his ministers, Paris became an occupied zone through the surrender and was directly under German rule.

Following the Allied invasion of Normandy on June 6, 1944, the French Resistance launched an uprising in Paris on August 19, occupying the police headquarters and other government buildings.

The city was liberated by French and American troops on August 25; the next day, August 26, General de Gaulle led a triumphant parade down the Champs-Élysées and organized a new government.

In the following months, ten thousand Parisians who had collaborated with the Germans were arrested and tried, eight thousand were convicted and 116 were executed.

.jpg)

Stern-looking Wehrmacht soldiers march along one of the city’s wide boulevards.

.jpg)

In Zucca’s paintings, the Nazis are portrayed as integrated into Parisian life.

.jpg)

.jpg)

A young family, including a man of military age, sits in the sun and eats cherries.

.jpg)

It shows Parisians fishing in the Seine.

.jpg)

.jpg)

Wehrmacht officers talk to a Parisian woman.

.jpg)

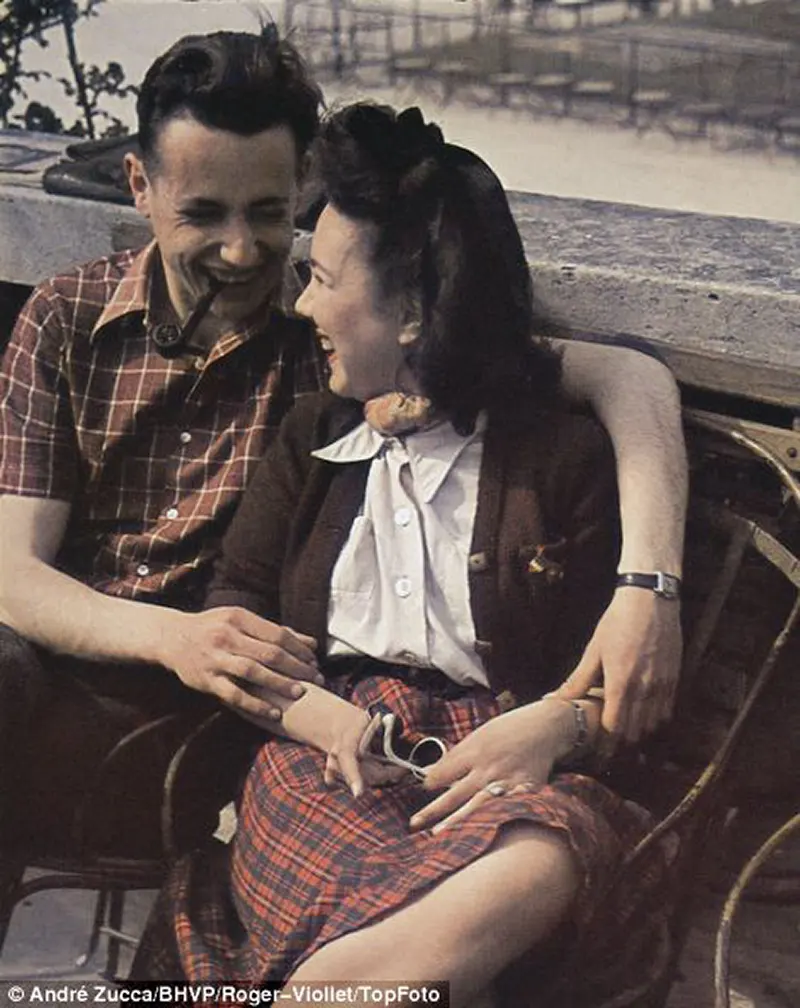

The series features many fashion-conscious women wearing fashionable outfits and makeup—a stark contrast to the harshness commonly associated with Nazi rule.

.jpg)

An elderly woman walks down the street wearing the yellow star that the Nazis forced Jews to wear.

.jpg)

A wagonload of meat.

A car that can run on natural gas.

Parisians cycle past a poster for the Nazi-sponsored exhibition “Europe Against Bolshevism.”

Historians say images like this one of a Nazi soldier marching freely with Parisians were meant to show the world that France was happy under occupation.

Zucca’s photos show women dressed in the latest fashion, courting young lovers and enjoying the French sun.

A German soldier observes lethargic-looking polar bears in the Ménagerie du Jardin des Plantes, the famous Paris zoo.

An elephant reaches out of its enclosure to take something from a boy’s hand.

Two fashionably dressed young men stand next to a tandem pulling a kind of carriage.

A sign advertises the exhibition “Europe Against Bolshevism,” which took place in Paris in 1942 under the patronage of the Nazi front organization “Anti-Bolshevik Action Committee.”

Parisians go about their business and get on the subway.

A section of the Seine is separated by a pontoon to form a swimming pool, which is visited by hundreds of Parisians who take advantage of this opportunity to cool off in the summer heat.

This poster, captioned “Murderers always return to the scene of their crime,” shows Joan of Arc kneeling in prayer with her hands bound as the city of Rouen burns below her.

Most of Zucca’s images depict Paris as a thriving, vibrant city full of food, laughter, and young families.

Against the backdrop of the Eiffel Tower on the Champ de Mars in central Paris, girls and boys play on what look like the first precursors of roller skates.

A soldier and civilians mill near the “Needle of Cleopatra” in the Place de la Concorde, one of three obelisks brought from Egypt in the 19th century and re-erected in Paris, London and New York.

A flower seller sits in front of her shop on a bright, sunny day.

Since most of the gasoline was diverted to the German armed forces to power their tanks, ships and aircraft, civilians were forced to look for alternative fuel sources for their vehicles.

A harried-looking man pulls a cart through the streets of Paris with two shabbily dressed girls.

A man in dirty clothes hurries down the street.

On a cool morning, Parisian commuters queue to board a bus.

Nazi soldiers are shown participating in Parisian life and shopping at the market.

The focus of this photo is a shapely woman leaning over the side of the bridge.

An elegantly dressed woman gets out of a bicycle taxi.

Poorer-looking Parisians at a run-down street market.

A woman walks down a Paris side street, past an elderly man wearing the Star of David badge that Jews were required to wear.

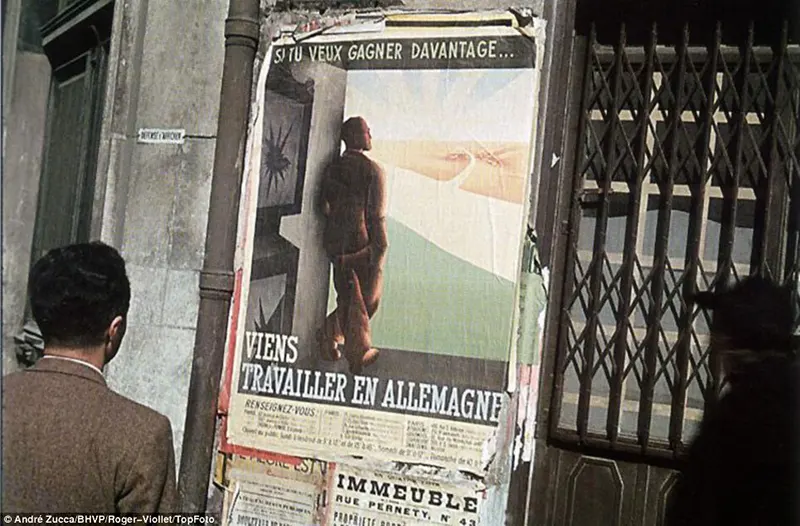

“If you want to earn more… come to Germany to work.”

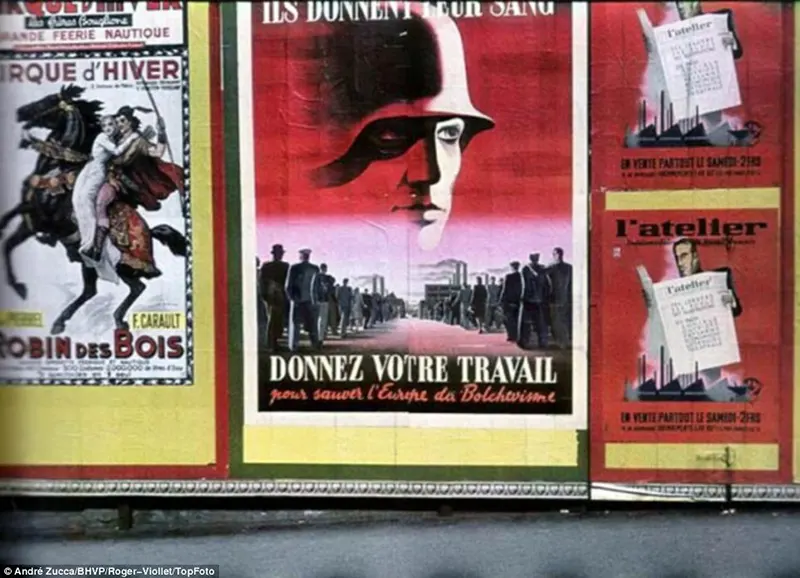

“You give your blood – give your labor to save Europe from Bolshevism.”

Street signs indicate the locations of German institutions in Paris. Below them, the French names appear in smaller print.

Marshal Philippe Pétain, a World War I hero who became head of the Vichy government during the Nazi occupation, is the centerpiece of a shoe store window.

A young woman checks her handbag while a man sits slumped on a walking stick in front of posters of the city’s famous Moulin Rouge cabaret.

A theater with an imperial eagle painted on its wall presents itself as a German soldiers’ cinema.

High-ranking German army officers stroll past a group of French people enjoying the afternoon in one of Paris’s street cafés.