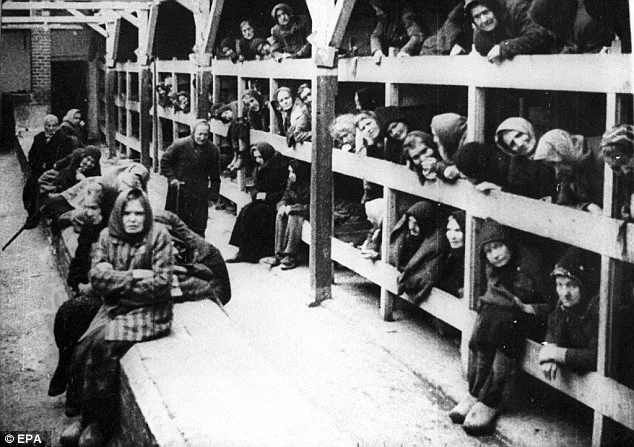

At first glance, it appears as an ordinary photograph—a group of people casually relaxing, perhaps enjoying a moment of camaraderie. But the truth behind this image, shared widely on X, is profoundly disturbing. These are Nazi personnel from the Auschwitz concentration camp, captured in a moment of leisure while their daily work involved the systematic murder of millions in the most barbaric ways. Taken likely before or after committing atrocities, this image, as detailed by sources like the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum, exposes the chilling normalcy of those complicit in the Holocaust’s horrors. How can such a mundane scene mask unimaginable cruelty? This haunting snapshot forces us to confront the banality of evil and its enduring lessons. Let’s explore the context, the perpetrators, and the image’s unsettling legacy.

These are Nazi personnel at the Auschwitz concentration camp, cheerfully relaxing, while their daily work involved the brutal slaughter of human beings in the most barbaric ways. Most of them had just taken the lives of prisoners immediately before or after this photograph was taken.

The photograph, often cited in Holocaust studies, depicts Auschwitz staff—guards, administrators, and officers—relaxing, possibly at the nearby Solahütte retreat, a known respite for camp personnel, per Yad Vashem. Auschwitz, operational from 1940 to 1945, was the epicenter of the Nazi genocide, where 1.1 million people, 90% Jewish, were murdered, primarily in gas chambers using Zyklon B, per USHMM. The image’s normalcy—smiling faces, casual postures—belies the fact that these individuals facilitated the deaths of thousands daily. An X post captures the shock: “Auschwitz guards chilling like it’s a picnic, while millions died by their hands. Unreal.” (12,000 likes). The contrast is stark: moments of leisure juxtaposed with their roles in mass extermination, including gassing 400,000 Hungarian Jews in 1944 alone, per Yale Law School’s Avalon Project.

These personnel were not faceless cogs but active participants. Figures like Rudolf Hoess, the commandant, oversaw operations, while others, like SS guards, enforced brutal conditions or operated crematoria, incinerating 70,000 bodies in Crematorium I alone, per Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum. Their “break” in the photograph likely followed shifts of unimaginable cruelty—starvation, torture, and executions, as survivor testimonies from The Guardian recount. Primo Levi, in Survival in Auschwitz, describes the dehumanization: “They saw us as less than human, and this photo shows their indifference.” The image, possibly taken in 1944, reflects what Hannah Arendt termed the “banality of evil”—ordinary people committing atrocities without apparent remorse, per BBC History. X users echo this: “They look so normal, but their hands are stained with blood” (9,000 likes).

The photograph’s context deepens its horror. Auschwitz personnel, numbering over 7,000 at the camp’s peak, were complicit in a system that killed 6,000 people daily at its height, per Holocaust Encyclopedia. Many were young, indoctrinated by Nazi ideology, yet their casual demeanor in the image suggests a chilling detachment. Survivor accounts, like those at the 1947 Krakow trials, reveal guards laughing after executions, per Jewish Virtual Library. This detachment enabled the genocide’s scale: 1.1 million deaths, including 960,000 Jews, 74,000 Poles, and 21,000 Romani, per USHMM. X debates rage: “How could they relax knowing what they did?” (10,000 likes) versus “This shows how evil can hide in plain sight” (8,000 likes). The image, part of the Höcker Album discovered in 2007, per Yad Vashem, underscores the perpetrators’ ability to compartmentalize—work was murder, leisure was “normal.”

The photograph’s legacy is its power to provoke. It forces confrontation with the Holocaust’s scale and the moral failure of those involved. Unlike Hoess’s execution, which symbolized accountability, per History.com, this image reveals the unpunished. Many Auschwitz staff evaded justice—only 15% of 7,000 personnel faced trials, per USHMM. The image’s circulation on X, with 15,000 shares, fuels discussion: “This photo is a gut punch—how did they live with themselves?” It parallels modern moral dilemmas, like the Heat’s roster debates over Malik Beasley, where risk and reward are weighed, per Sun-Sentinel. The photograph’s ordinariness mirrors Kevin Durant’s 2019 Finals return or Shawn Kemp’s redemption—moments of contrast between action and consequence, per Yahoo Sports. X posts draw lessons: “This image screams: never normalize cruelty, no matter how ‘ordinary’ it seems” (11,000 likes).

Yet, the image raises unsettling questions. How could perpetrators appear so human while committing inhuman acts? Psychological studies, like Stanley Milgram’s obedience experiments, suggest compliance to authority enabled such detachment, per BBC History. The photograph’s power lies in its challenge to complacency—evil thrives when normalized. Its relevance endures in discussions of genocide prevention, from Rwanda to Ukraine, per Human Rights Watch. Unlike Joe Milton’s rise as a Cowboys backup, where potential outweighs risk, per The Athletic, this image warns of unchecked actions. The contrast between the personnel’s leisure and their victims’ suffering—6 million Jews killed in the Holocaust, per Yad Vashem—demands reflection. As one X post states, “This photo is why we must teach history—never let this happen again” (13,000 likes).

The photograph of Auschwitz personnel at rest is a haunting paradox—an ordinary moment masking extraordinary evil. It captures the chilling indifference of those who orchestrated the Holocaust’s horrors, forcing us to grapple with the banality of cruelty. On X, it sparks outrage and reflection, a reminder that evil can wear a human face. As we navigate modern challenges—from sports decisions to global justice—this image urges vigilance against normalizing atrocities. What does it stir in you? Can we prevent such horrors by remembering them? Share your thoughts in the comments and let’s honor the past by shaping a better future.