Berlin in the 1920s was a city of social contrasts. While a large portion of the population still struggled with high unemployment and deprivation after the First World War, the upper classes and a growing middle class gradually rediscovered prosperity and transformed Berlin into a cosmopolitan city.

During this decade, Berlin emerged as the intellectual and creative center of Europe, pioneering modern movements in literature, theater and the arts, as well as in the fields of psychoanalysis, sociology and science.

Germany’s economy and politics suffered at that time, but cultural and intellectual life flourished. This period in German history is often referred to as the “Weimar Renaissance” or the country’s “Golden Years.”

The most important artists of the time (Bertolt Brecht, Otto Dix, Max Liebermann, Erich Kästner, Joachim Ringelnatz, Billy Wilder and many others) met at the Romanisches Café on Kurfürstendamm and Josephine Baker brought the new Charleston dance sensation to Germany with her performance in 1926 at the Nelson Theater on Kurfürstendamm.

In 1928, Brecht’s “Threepenny Opera” celebrated its premiere at the Theater am Schiffbauerdamm and from there achieved worldwide fame.

In addition to the boom in Berlin’s nightlife with entertainment shows and variety shows, the city also made great progress during the day.

In 1921, the world-first AVUS (Automobile Traffic and Training Route) was built through the Grunewald forest, Tempelhof Airport opened in 1923, and the radio tower was opened to the public for the Third Radio Exhibition in 1926. The first Green Week took place in 1926 and attracted an enormous 50,000 visitors.

.jpg)

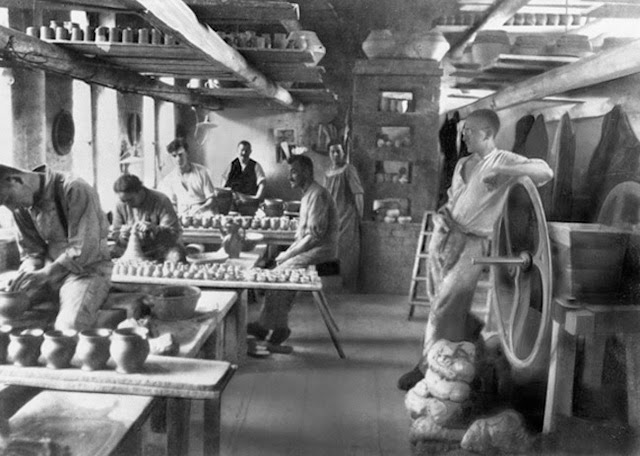

Newspaper sellers on stools, Berlin, 1927.

The Weimar Republic began amid several significant movements in the visual arts. German Expressionism had already begun before World War I and remained highly influential throughout the 1920s, although artists increasingly opposed Expressionist tendencies throughout the decade.

A sophisticated, innovative culture developed in and around Berlin, including sophisticated architecture and design (Bauhaus, 1919–33), a variety of literature (Döblin, Berlin Alexanderplatz, 1929), film (Lang, Metropolis, 1927, Dietrich, The Blue Angel, 1930), painting (Grosz) and music (Brecht and Weill, The Threepenny Opera, 1928), criticism (Benjamin), philosophy/psychology (Jung), and fashion. This culture was often viewed by right-wingers as decadent and socially disruptive.

At this time, the film industry in Berlin made great strides both technically and artistically, leading to the emergence of the influential movement of “German Expressionism.”

Sound films also enjoyed increasing popularity among the general public throughout Europe and were often produced in Berlin.

.jpg)

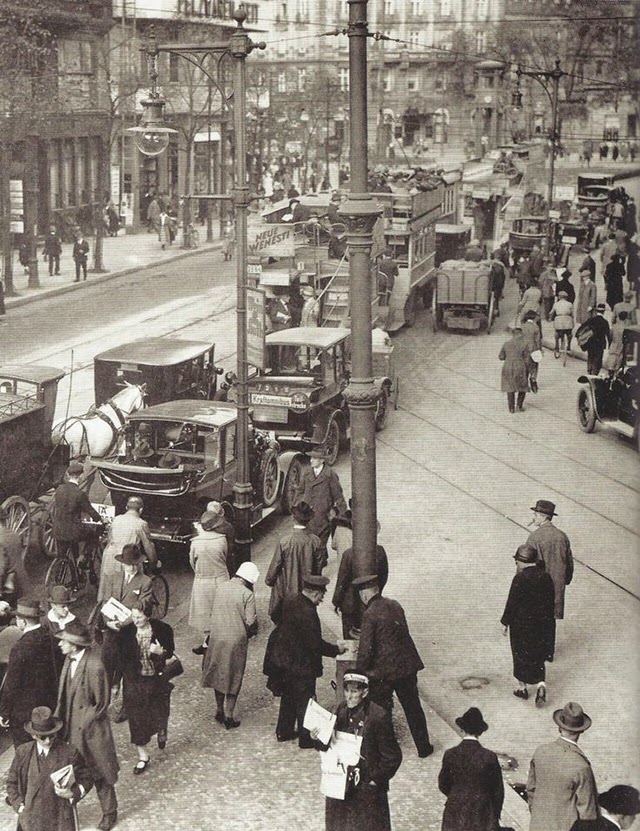

Street scene, Berlin, 1928.

The so-called mystical arts also experienced a revival in Berlin during this period; astrology, occultism, esoteric religions, and unusual religious practices became more generally accepted and more popular with the masses as they entered popular culture.

The University of Berlin (now Humboldt University of Berlin) developed into a significant intellectual center in Germany, Europe, and the world. From 1914 to 1933, the natural sciences received particular support.

Albert Einstein rose to public prominence during his years in Berlin and was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1921. He was director of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physics in Berlin and only left this position when the anti-Semitic Nazi Party came to power.

.jpg)

Friedrichstrasse, Berlin, circa 1927.

German veterans of the First World War begging on the streets of Berlin in 1923

Politically, Berlin was considered a stronghold of the left. The Nazis called the city “the reddest city [in Europe] after Moscow.”

Nazi propagandist Joseph Goebbels became his party’s Gauleiter for Berlin in the autumn of 1926 and had only been in office for a week when he organised a march through a communist-minded district that degenerated into street riots.

The communists, who advocated the motto “Beat the fascists wherever you find them!”, had their own paramilitary organization called the Red Front Fighters League to fight against the Nazi Sturmabteilung (SA).

In February 1927, the Nazis held a rally in the “red” stronghold of Wedding, which escalated into a violent brawl. “Beer glasses, chairs, and tables flew through the hall, and the seriously injured were left lying on the floor covered in blood. Despite the injuries, it was a triumph for Goebbels, whose followers beat up about 200 communists and chased them out of the hall.”

.jpg) In Berlin and other parts of Europe devastated by the First World War, prostitution increased. By the 1920s, this means of survival became, to some extent, normal for desperate women and sometimes men.

In Berlin and other parts of Europe devastated by the First World War, prostitution increased. By the 1920s, this means of survival became, to some extent, normal for desperate women and sometimes men.

During the war, sexually transmitted diseases such as syphilis and gonorrhea spread so rapidly that the government had to address them.

Soldiers at the front contracted these diseases from prostitutes. The German army responded by licensing certain brothels, which were inspected by its own doctors, and by providing soldiers with vouchers for sexual services in these establishments.

Homosexual behavior was also documented among front-line soldiers. Soldiers who returned to Berlin after the war had a different attitude toward their own sexual behavior than they had a few years earlier.

Although prostitution was frowned upon by respectable Berliners, it persisted to the point of becoming entrenched in the city’s shadow economy and culture.

.jpg)

Schoolchildren, Berlin, 1925

Along with prostitution, crime also developed in the city. It began with petty thefts and other crimes related to the need for survival after the war.

Berlin eventually gained a reputation as a hub for drug trafficking (cocaine, heroin, tranquilizers) and the black market. Police identified 62 organized criminal gangs, so-called “ring clubs,” in Berlin.

The German public was also fascinated by reports of murders, especially “lust murders” or “lust murders.” Publishers responded to this demand with inexpensive crime novels called Krimi, which, like the film noir of the era (such as the classic M), employed methods of scientific investigation and psychosexual analysis.

.jpg)

Erik Charell performing with dancers in a variety show, Berlin, 1925.

In addition to the new tolerance for behaviors that were still technically illegal and considered immoral by large sections of society, there were other developments in Berlin culture that shocked many visitors to the city.

Thrill seekers came to the city in search of adventure, and booksellers sold numerous editions of guidebooks to Berlin’s erotic nightspots.

It is estimated that there were 500 such establishments, including a large number of homosexual meeting places for men and lesbians; some also allowed transvestites of one or both sexes; otherwise, at least five establishments were known to cater exclusively to a transvestite audience.

There were also several nudist spots. During the Weimar Republic, Berlin also had a sexual museum, located in the Institute for Sexology run by Dr. Magnus Hirschfeld.

.jpg)

Terrace of the Romanesque Café in Berlin, 1925.

.jpg)

A Berlin cabaret performance, 1927.

.jpg)

The sculptor and engraver Renée Sintenis and her Studebaker in Berlin, 1928.

.jpg)

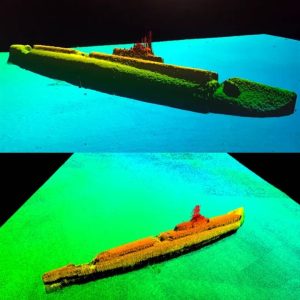

Max Krehan’s ceramics workshop at the Weimar Bauhaus, 1924.

.jpg)

Berlin’s Tempelhof Airport opened in 1923. Its first building? A small hut for the first construction workers.

.jpg)

Margo Lion and Wilhelm Bendow, Berlin, 1927.

.jpg)

Summer refreshment for city dwellers, 1925.

.jpg)

Rush hour, Berlin, 1927.

.jpg)

.jpg)

Fun at Wannsee, Berlin, 1925.

.jpg)

Cabaret dancers, 1927.

.jpg)

Sign at a hair salon offering special prices for the unemployed, 1927.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

“Bloody May” in Berlin, 1929. Arrest after a street brawl.

.jpg)

From 1924 to 1929, between the end of hyperinflation and the stock market crash.

.jpg)

Rebelliousness, Berlin, 1926.

.jpg)

Election Sunday in Berlin, which saw major propaganda campaigns by every party. KPD propaganda vans crossing Alexanderplatz. Berlin, 1924.

.jpg)

Karl Liebknecht House, headquarters of the KPD from 1926 to 1933.

.jpg)

Archive of the Essen Communist Party’s election campaign in the presidential elections of March 1925.

.jpg)

Cocaine dealer “Koks Emil” on the streets of Berlin, 1929.

.jpg)

Theater in Berlin, 1925.

.jpg)

Hiding cocaine, Berlin, 1925.