American Sherman tanks fight against German Panthers blocking a small intersection in St. Sever.

By George J. Winter, Sr.

The Normandy landings, the fighting at Saint-Lô and Caen, Operations Goodwood and Cobra, and the subsequent Argentan-Falaise Pocket have always attracted considerable attention from historians with regard to the early struggle for supremacy in France. Given their overall significance, this is rightly so. Overshadowed by these major events are the countless actions by small units that were equally violent and nerve-wracking for the German and Allied participants. But the sum total of these lesser-known and now almost forgotten engagements formed the basis of the more famous military operations. One of these smaller affairs, involving a duel between a German M4 Sherman tank and a German Mark V Panther tank, occurred southeast of Saint-Sever-Calvados on August 4, 1944.

At the end of July 1944, the Cobra outbreak reached its peak as the armored columns of the U.S. First Army spread out along the foot of the Contentin Peninsula. On August 3, Combat Command B (CCB), 2nd Armored Division, divided into two columns, reached the Sept-Freres area and the village of Courson further west. The Combat Command had been split into two columns at the beginning of the offensive for better control. The two sectors were spearheaded by Colonel Paul A. Disney and Brig. Gen. Isaac D. White, who also commanded the CCB. Although Disney’s command had been designated the left column at the beginning of the campaign, the vagaries of battle and movement placed it on the right of White’s unit.

Both Disney and White were experienced commanders. White, a graduate of Norwich University, had served in the mechanized cavalry since the early 1930s. In June 1942, he was appointed commander of the 67th Armored Regiment, and Disney assumed command of the CCB on April 5, 1943. Paul Disney, White’s junior commander, had a successful combat record, earning him the Silver and Bronze Stars with Stars, as well as the Purple Heart. He had been promoted to full colonel shortly before the 2nd Armored Division’s landing in Normandy and was now at Courson.

Courson’s column consisted of the 2nd Battalion (67th Armored Regiment, Companies B, E, and F) and the 3rd Battalion (41st Armored Infantry Regiment) under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Marshall Crawley. Artillery and engineers, as well as a platoon from the 702nd Anti-Tank Battalion and a medical detachment, provided support. The column also included Colonel Thomas A. Roberts, Jr., artillery commander of the 2nd Armored Division. A West Point graduate (class of 1920), Roberts was an innovative and aggressive artilleryman. The Illinois native was awarded the Silver Star on July 29, 1944, for his military career, which spanned more than half of his 44 years.

Saint-Sever-Calvados: German Panthers waiting

The orders for the following day, Friday, August 4, called for Disney’s command to enter Courson, advance southeast through Saint-Sever-Calvados, and onto a main road to Vire, with the final objective being Champ-du-Bolt. Disney’s command began at 5:00 a.m. and was spearheaded by Company F of the 67th Panzer Regiment and the 3rd Battalion of the 41st Panzer Infantry. The rest of his command provided support, with the 110th Infantry Regiment of the 28th Infantry Division advancing on the right.

Via Courson, the column continued its advance toward Saint-Sever-Calvados. The unit reached the town around 9:30 a.m. Despite being under enemy artillery fire, the command passed through the town and continued slightly southeast. Here, it reached a wooded area on the edge of the Forêt de Saint-Sever, the Forest of Saint-Sever.

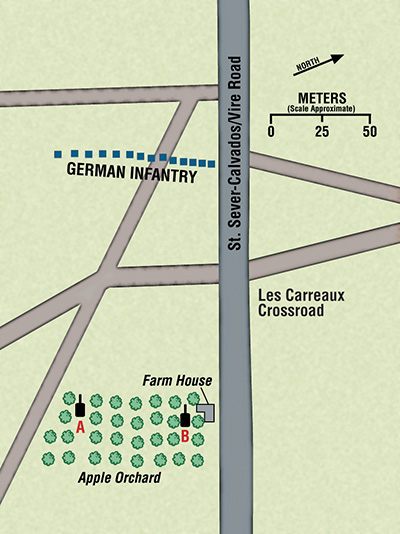

About a mile southeast of the city, directly in the path of the American advance, two Mark V Panthers were waiting in an orchard to the left of the Saint-Sever-Calvados/Vire road. These monster tanks, weighing over 44 tons, had good visibility of the movements 180 to 270 meters away and were heavily protected by 80 mm (3.2 in) of steel on their sloping front. The Panthers were armed with a 7.5 cm cannon and machine guns in the hull and turret. The Mark V was undoubtedly one of the best tanks of World War II.

From their position, the German Panthers covered a road complex that included not only the main road to Vire, but also the Les Carreaux road, which led into the town from the north and crossed it. On the German front, there was also a narrow dirt road that branched off at an acute angle from the road to Vire and passed immediately to the left of the orchard.

In the small wood, one of the German tanks had taken up a position near Vire Road and a farm building adjacent to the main road to the right. The second Panther was positioned about 50 meters to the left, and both vehicles had a line of fire directly in front of them.

A battered Viennese infantry battalion had dug in about 150 meters in front of the tanks to provide cover. Its position, which offered reasonably good cover, lay within the intersection formed by Vire Road and the track. SS Oberjunker Fritz Langanke observed the partially foggy road and track from his tank turret.

He had arrived at the crossroads early in the morning of August 4, having received direct orders from the commander of the 2nd SS Panzer Regiment, under the command of Sturmbannführer (Major) Rudolf Ensling, to set up a roadblock. Langanke initially positioned his Panther on the right side of Vire Road under cover of the trees and, once they arrived, helped position the infantry support. Following the arrival of his company commander, Obersturmführer (First Lieutenant) Joachim Schlomka, who had also been ordered to the roadblock, both tanks crossed the road and entered the orchard. Langanke moved to the right corner of the grove near the road, and Schlomka positioned his tank at the left angle near the track.

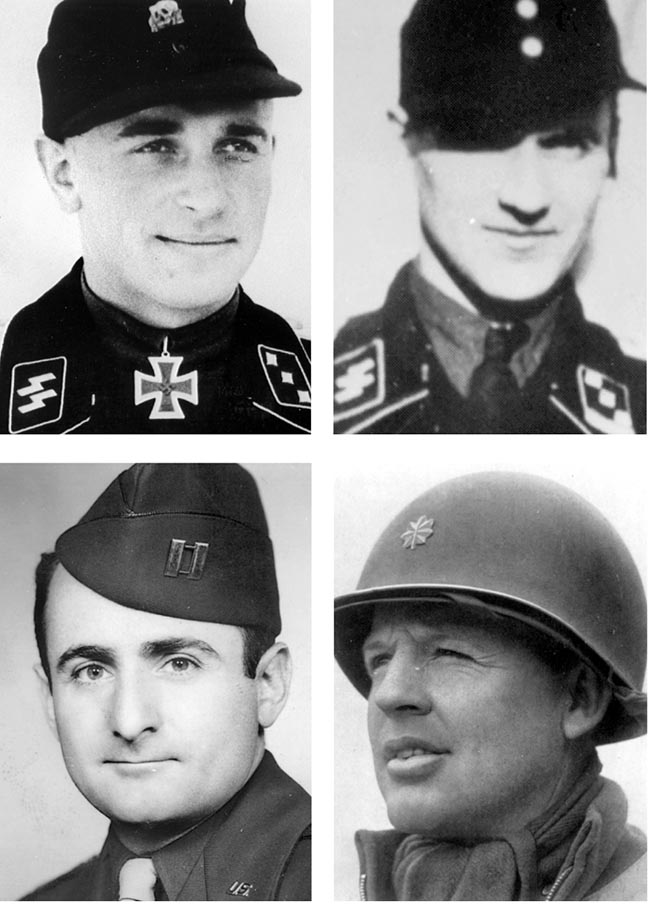

Fritz Langanke had just turned 25 and was a veteran of the campaigns in Poland, France, the Balkans, and Russia. As a platoon commander of the 2nd Company of the 2nd SS Panzer Regiment “Das Reich,” he had already recorded the destruction of ten Allied tanks. Quick to react in combat situations, he had led his men the previous month during the general German retreat in an action that earned him the Knight’s Cross. Langanke’s skill, determination, and luck enabled him to bring the remnants of his platoon and a motley crew of approximately 600 infantrymen and their vehicles through the American lines.

Alongside Langanke, the remaining crew members were waiting in Panther No. 211. Under the commander’s command, the gunner, Rottenführer (Corporal) Meindl from the Sudetenland, and Sturmmann (Corporal) Fahnrich, the loader from Duisburg on the Rhine, served. Rottenführer Pulm, who lived in Düsseldorf, was the radio operator and machine gunner. The youngest member of the group was the driver, Sturmmann Heil from Leipzig. Heil had joined the crew as a replacement for the previously wounded driver.

In the left corner of the orchard stood Joachim Schlomka’s Panther No. 201. Schlomka, wounded five times during the war, had joined the division in 1942. The calm, unflappable North German was awarded the German Cross in Gold for his actions in Russia and at Percy in France. At Percy, the 66th Panzer Regiment of the 2nd Panzer Division had suffered heavy losses just a few days earlier, including an entire tank platoon from G Company. Schlomka’s stubborn defense, along with two Panthers from his 2nd Platoon, helped prevent the Americans from reaching the town for 24 hours. Two Sherman thrusts failed, and the Americans were held back until the Germans withdrew that evening.

Although it wasn’t mentioned in his award of the German Cross in Gold, Schlomka oversaw the rescue of American wounded from their damaged tanks, as well as the search for shelter in French houses and medical supplies. He also ordered that the wounded “remain in the French houses” until they were returned to their units.

By morning, fog still limited visibility at the intersection of the main road and the dirt track, but it didn’t hinder the advance of Disney’s column. As Langanke watched, an American tank came into view. He could see the American commander looking out of the turret as the vehicle slowly approached. The engine in Langanke’s tank shut down, forcing the crew to move the turret manually. They did so and fired a shot. The shell missed, and the American tank drove past behind the farm.

While Schlomka held his position, the driver of Langanke’s Panther started the engine, reversed, and hurried to the road, which was slightly higher above the orchard. When he reached the road, the turret already turned to the right, Langanke gave the necessary order to fire on the American tank, which was continuing down the road. The shell destroyed the Sherman’s engine at a distance of about 50 meters. Langanke could see the American commander jump out of the tank.

Expecting more Shermans, Langanke ordered the tank to veer to the left. As expected, it now faced two more American tanks at a distance of approximately 137 meters, one on either side of the Vire Road. At Langanke’s command, the gunner fired. Langanke recalled: “We took them out with just one salvo each.”

Almost immediately after this success, while still en route, the German looked to his left and saw infantry running with their hands raised. He mistakenly took them for surrendering Americans. In fact, they were German infantry who had surrendered. Without realizing it, the tank crews had lost much of their infantry support, which was absolutely essential for the close-quarters combat they were engaged in.

Sometime around noon, after Langanke’s tank had returned to the orchard, his regimental commander, Rudolf Ensling, appeared. As part of his inspection of the roadblocks set up by the regiment, Ensling stayed long enough to assess the immediate position. Satisfied with the tank crew’s actions, he left the field.

Both Panthers now took up positions and waited for the next American attack. The German commanders watched from their turrets, their view obstructed by bushes and trees to the right and left. Schlomka was particularly concerned about the hill ahead. It rose well above street level and was about 800 to 900 meters away. In his opinion, the elevation offered a clear view for artillery observation and possible fire on their position. Indeed, Schlomka’s fears proved to be true.

“Stop the enemy or die”

As for Langanke, the relentless and overwhelming pressure of the American advance over the past two weeks had left him with few illusions about his future. The desperate conditions of the enforced German retreat had created an atmosphere of distress that certainly made him a tougher opponent. He later recalled: “It was a hopeless situation. We tried by all means to stem the tide, no matter how dangerous it was and how slim the chances of survival. … There were only two options: stop the enemy or die.”

The Americans, now stuck on the road, decided to defend their position and flank the German positions with soldiers from the 41st Panzer Infantry Regiment. To dislodge the positions, artillery fire would first be directed at the area. For this purpose, the hill near Schlomka was used as an observation post to locate the enemy’s position.

Among the spectators who had climbed to the top of the hill was the commander of E Company, Captain James R. McCartney of West Virginia. McCartney, a Pennsylvania native and graduate of West Virginia University, was idling his Shermans on the road, getting a good overview of the situation ahead. “Nothing caught our attention like an 88 or a Panther,” he later said. At the top of the rise, he spotted Colonel Roberts, the division artillery commander. McCartney remembered him as an “impulsive man.” He heard the colonel say, “We have to get through this roadblock.” Soon, Roberts left the hill, and McCartney followed, but not before scanning the area with his binoculars. “I couldn’t see the enemy, but it wasn’t a good place for the Germans,” he recalled years later.

Shortly before McCartney reached the ridge, Captain Louis H. Tankin, a graduate of Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore and a native of Maryland, was radioed to rescue three wounded German soldiers. Tankin, in charge of the column’s medical section, headed for the front line.

Tankin later recalled the jeep ride: “We followed the call further into a hilly, densely wooded area. I heard small arms fire and then came to the edge of a clearing in the forest,” which bordered a large ammunition depot.

Tankin got out of the jeep, while his driver and medic stayed behind. He later reported: “I got out and went to a lieutenant from the 28th Division. He pointed out three German soldiers. They were badly wounded.” Moments after Tankin’s arrival, enemy fire forced the lieutenant to order the withdrawal of his men in danger from the area around the garbage dump. Thus, the medical officer was left alone with the wounded enemy. “I called my medic and told him to throw me a grappling hook. … I attached it to the wounded. They were pulled out one by one.”

After the Germans were taken to the rear by ambulance, Tankin returned to the column, where he received word that he was to report to the commanding officer of the 2nd Battalion, 67th Armored Regiment. That commander was Lieutenant Colonel J. Davis Wynne, a 35-year-old man from Arizona. When Tankin found Wynne, he was standing next to his command half-track, which was part of the stalled column on the road. The medic remembered Wynne’s words: “Three tanks ahead of us have been hit. Go in and get them out.” The medical officer was warned that he had only 15 minutes before the area would come under fire and wondered if he, his driver, and his medic would ever return. The latter two were medic Private Stanley R. Yarmuth and driver Private Russillo, whom Tankin described as a tough, young Italian-American. As their jeep drove down the road, they passed American tanks and armored vehicles lined up one behind the other. After receiving instructions, they continued on, approaching the disabled Shermans.

Before Tankin arrived, Shlomka, who had joined Langanke’s tank, observed a jeep bearing a red cross approach the disabled American tanks. There, the occupants were tending to the tank crews. Through his binoculars, Shlomka saw another jeep (this time Tankin’s) approach, stop near the tanks, and then continue toward the German position.

Although Schlomka had no doubts about the vehicle’s occupants’ role, their advance puzzled him. He hadn’t noticed any destroyed tanks or wounded Americans on his journey to support Langanke, and thus there were no American troops behind their position that the American jeep might be heading for. Concerned that the Americans in the jeep might observe his position and the strength of his troops and report back if they were allowed to return, “we tried to give them a sign of refusal, but they didn’t stop until they reached Langanke’s tank.”

Tankin’s memoirs do not indicate why he went to the German positions. He may have been looking for more German or American victims to treat.

In any case, Shlomka ordered Tankin and his men to stay in the jeep. At that precise moment, the American artillery opened fire. The German recalled: “I couldn’t leave the jeep and the medics standing on the road under the fire of their own artillery.” To solve his problem, before returning to his tank in the orchard, Shlomka ordered an infantryman to escort the Americans to the rear in the jeep. He instructed them not to use their radios but to provide aid to the wounded they encountered along the way.

The artillery fire that now enveloped the area was heavy and, from the German perspective, seemed to be concentrated on the orchard. The crews were pinned down as shrapnel hit the tank hulls and were under immense stress. They were hungry, thirsty, and almost completely exhausted, having had little opportunity to rest or sleep in the past week. Despite the situation, the crew members began to fall asleep. Langanke even swapped places with his gunner, Meindl, so he could lean his head against the telescopic sight and get some sleep.

It didn’t take long. Soon, Langanke climbed back into his usual turret position and checked his front. He recalled: “A Sherman appeared on the road, turned onto the track in front of us, and raced at full speed toward our orchard, its gun aimed directly at us.” The sudden appearance of the Americans surprised the Germans, as it contradicted what they considered the usual pattern of an American advance—resistance culminated in a prolonged artillery barrage, an air attack, and finally a tank assault.

Schlomka also saw the approaching Sherman and kicked his sleeping gunner. The man fired, believing the weapon was set for armor-piercing shells. The shell went over the American, as did the second and third bullets. The German tankers later discovered that the weapon had been set to a previous setting for high-explosive shells.

A nerve-wracking game with the chicken

Langanke observed the missed shots and realized: “Now it was a life-and-death race between the Sherman crew and us. Their gun was aimed directly at us, but they had to correct the elevation. We had the correct elevation but were frantically slewing (by hand) to find the final alignment. I had thrown my head out of the cupola and, as we were ready to fire, had the impression that my eyes were exactly in line with the Sherman’s gun. Our first shot destroyed the tank. The daring, straight-ahead, narrowly successful attack ended about 45 meters in front of us. The commander was lucky to parachute and escape, as far as I could see. This was the most daring and extraordinary single action by an American soldier that I witnessed during the war.”

The shelling and air attacks intensified again. Because the hatches were closed for safety reasons, heat built up, further straining the crews’ nerves. The shelling blew out the radio antenna on Langanke’s vehicle and destroyed the telescopic sight on the cupola, leaving the commander unable to detect enemy movements. Nevertheless, Langanke nodded off again—a sure sign that he had reached his limits.

Eventually, the shelling stopped, and shortly afterward, machine gun fire hit Langanke’s tank, indicating that enemy infantry was not far away. Schlomka, in the neighboring Panther, spotted infantry advancing from the left. “I knew they would surround us shortly. I ordered my driver to first reverse toward the road and then to the right. After about 100 meters, I stopped to provide covering fire for Fritz.”

Langanke was finally jolted out of his lethargy by a combination of machine gun fire, the approaching start of Schlomka’s tank, and the impact of an uprooted tree against his Panther. Assuming his company commander was on the road to engage Shermans, Langanke ordered the driver Heil to follow him, while he took the risk of opening the turret hatch and peering over the edge. Reaching the road at high speed, the Panther turned around, taking a volley of hits. Although Heil and Meindl could see nothing through their ports due to hit damage, Langanke could see several Shermans lined up to the left of the road behind one of the previously destroyed tanks. He recalled that they were positioned one behind the other, “so that only the gun of each tank could fire along the turret of the vehicle in front, and they fired volleys.”

Langanke reacted quickly to place the disabled American tank between himself and the Shermans. This maneuver forced each enemy tank to circle the disabled Sherman and come into sight one by one, giving the Panther a direct opening for fire. Langanke explained his plan to the crew and ordered Heil over the intercom to veer to the left. While turning, the Panther was hit so hard by a salvo, primarily on its sloping front plate, that the weld between the front and side walls of the hull burst open.

“Emergency exit!”

The shock of the blows also destroyed the radio and interrupted normal communication with the crew. While Fahnrich, the loader, shoved grenades into the breech, Meindl responded to Langanke’s hand tapping him on the shoulders (left/right) to fire. Unfortunately, in the noise, Heil couldn’t hear the commander’s call to change direction “straight ahead” and continued to turn left, causing the tank to cross the road broadside.

From his post further down the road, Shlomka, standing in his open hatch, could see that Langanke had turned “with the right flank of his tank toward the nearby house on the road.” Shlomka could also see that American infantry had occupied the farmhouse and that rocket-propelled grenades were threatening his comrade’s tank. Shlomka ordered armor-piercing shells fired at the building. But at that moment, Shlomka saw an explosion that rocked Langanke’s tank, which had been hit by a rocket-propelled grenade from the right side of the road.

In his tank, Langanke caught a glimpse of his loader, “standing inside a large torch. It was as if many sparklers were burning. I just shouted, ‘Get out of the car!’ and jumped out of the cupola into the ditch.” Although the gunner and the wounded loader followed their commander, Heil and Pulm were caught in machine gun fire inside the burning tank. In a desperate attempt to escape, Heil pulled the Panther close to the side of the road. Then he and Pulm opened their hatches and jumped into the safety of the ditch.

While Langanke and his crew escaped the doomed Panther, Schlomka silenced the fire from the outbuilding with his 7.5 cm gun and drove the American infantry on the left flank into cover with his machine guns in the turret and hull. As they reached Schlomka’s Panther, the dismounted German crew watched as one explosion after another rocked their burning tank.

The crew of the destroyed Panther then returned to their regiment’s command post, about 800 meters away. Meanwhile, Schlomka’s Panther slowly retreated, using the sloping road contours as cover from enemy fire.

By late afternoon, Colonel Disney’s column secured and consolidated its position for the night. Lieutenant Colonel Wynne’s 2nd Battalion withdrew after being relieved by tank destroyers. The battle for the roadblocks was over, but like so many other smaller skirmishes, it was short, fierce, and not without casualties.

The Germans lost over 100 infantrymen, most of whom were taken prisoner; a Panther tank was destroyed and a crew member wounded. They held off the Americans for the entire day.

The Americans lost five tanks, 15 killed or wounded, and three medical detachments from the armored column were captured. Another 30 losses marked the efforts of the armored infantry flanking the tanks in the orchard. But then they continued their unstoppable advance ever deeper into the heart of France.

epilogue

Captain James R. McCartney, CO—E Company, 67th Armored Regiment, survived the war. He remained in his command until being transferred to a staff position shortly before the Battle of the Bulge. He was the last of the company’s original tank commanders to land in France on June 14, 1944.

Captain Louis H. Tankin, commander of the medical department of the 48th Armored Medical Battalion, survived the war. He was transported to Germany and held in a prisoner of war camp until the Russians conquered the area. Although he was released, he endured horrific experiences on his journey by foot, truck, and train to Odessa, and finally home.

Colonel Thomas A. Roberts, commander of the 2nd Armored Division Artillery, was killed shortly after leaving the artillery observation post on the hill. He and all members of his forward observation tank were killed when the vehicle was hit by anti-tank fire.

Obersturmführer Joachim Schlomka, commander of the 2nd Company of the 2nd SS Panzer Regiment, survived the war. He was promoted to captain and appointed regimental adjutant before the Battle of the Bulge. After the surrender, he spent ten years as a Soviet prisoner of war.

Oberjunker Langanke survived the war “by sheer luck.” He rose to the rank of Obersturmführer and became commander of the 2nd Company of the 2nd SS Panzer Regiment. After the war, he was held prisoner by the Americans for two years, spending a third of his time as “His Majesty’s guest.”

Within a few weeks, Rottenführer Meindl and Sturmmann Fahnrich were encircled on the Seine near Elbeuf by units of the 66th Panzer Regiment. They drowned while attempting to swim across the river. Rottenführer Pulm took command of a Panther. He was killed by a Russian grenade splinter near St. Pölten, Austria, in the final days of the war.

Stormman Heil survived the war.