By Alan Davidge

In the early morning hours of June 6, 1944, a 20-year-old German soldier hurried to his post at Resistance Nest 62 (WN62) above Omaha Beach to man his MG 42 machine gun. Before him, over 34,000 American soldiers drifted across the English Channel, waiting for their chance to land on this beach and secure their place in history. Thanks to Cornelius Ryan, this date will always be remembered as “The Longest Day,” but for many of these young soldiers, it would prove to be the shortest day of their lives.

For Heinrich “Hein” Severloh, the son of a farmer from Baden-Württemberg, who had never fired a shot in anger, it was the day he became the “Beast of Omaha.” This account describes how he behaved for nine hours that day and how he lived with the consequences of his actions for the next 60 years.

“Hey, it’s starting!” The voice of his lieutenant, Bernhard Frerking, awoke Corporal Severloh from his sleep in a small French farmhouse a few kilometers inland. Everyone in the 352nd Infantry Division had been expecting this for weeks and knew how to react. Field Marshal Rommel had always said that in the event of an inevitable invasion, the enemy had to be repulsed within 24 hours, or the war would be lost. But at that moment, Rommel was celebrating his wife’s birthday on the other side of Normandy, and the Führer was enjoying a night’s rest that no one dared to disturb.

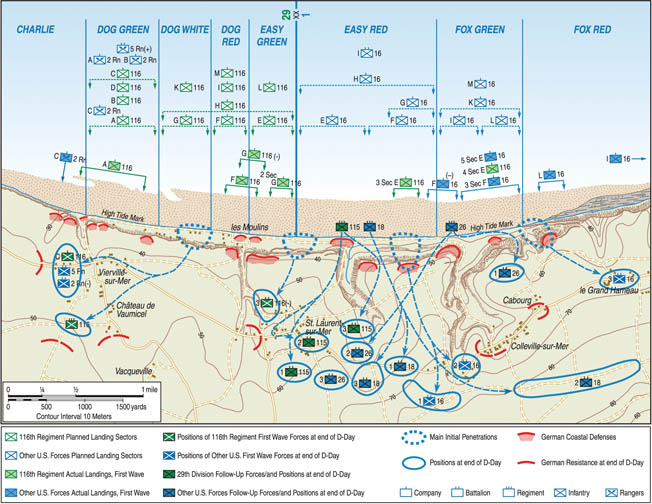

WN 62 was the strongest of the 15 strongpoints overlooking what would later become Omaha Beach. They stretched from WN 60 above Cabourg Draw (codenamed Exit F-1) near the cliffs at the eastern end to WN 74, four and a half miles west, just beyond the small coastal village of Vierville.

WN 62 was approximately 325 square meters in area and was located on the northern slope of the cliff, giving it an excellent field of fire all the way to the beach. It contained emplacements for two 75 mm cannons, two 50 mm anti-tank guns, two 50 mm mortars, and several machine guns, including an MG 34 on an anti-aircraft mount and two pre-war Polish water-cooled guns.

Not all of these guns were operational on June 6. Like many other sites, this one was under construction, as Hitler wanted to continually improve his Atlantic Wall. The entire area was fenced with barbed wire and protected by minefields. In addition, there was a water-filled anti-tank ditch to make it difficult for invaders to advance from the beach.

WN 62 was also located adjacent to the Colleville-sur-Mer bulge (codenamed Exit E-3), which the Allies had chosen as one of the main exits from the beach. It was inevitable that many assault platoons would be ordered to land at this location to facilitate their advance inland.

Severloh’s MG 42, capable of firing 1,200 rounds per minute, was positioned seven meters from the entrance to Lieutenant Bernhard Frerking’s observation post. In addition to fending off intruders, Hein’s job was to protect his officer and enable him to carry out his vital task: coordinating fire on the targets he identified with a telescope through the slit in his bunker.

Frerking’s vital information was transmitted to the communications bunker equipped with a transceiver several meters above the slope. It was then relayed to the battery further inland at Houtteville, less than three kilometers south of Colleville-sur-Mer and close to the farm where they were quartered. This battery could fire a storm of 105mm shells onto the beach as soon as the attackers appeared. The coordinates had already been provisionally agreed upon, and there had been some practice firing with dummy shells to avoid damaging the beach obstacles carefully placed along the coast and to rip out the hulls of any landing craft that made it onto the beach. Rommel had done his best to cover all angles.

It was up to Frerking, Severloh, and the twelve other men of the 352nd Division to keep the Allies away from their coastal sector. They had the support of 27 soldiers of the 726th Grenadier Regiment and one of the best-located strongpoints on the French side of the English Channel. While they weren’t strong enough in numbers, their arsenal was impressive, and Heinrich wouldn’t let his lieutenant down. He had no idea how the day would unfold, but Hein was determined to do his duty.

Hein appears to be a quiet, practical young man who reliably performed his duties, showed initiative, and was respected by his officers. The son of a farmer, he was drafted in 1942 and suffered frostbite on the Russian front before even seeing action. An inappropriate remark about the negligence of his company’s cook led to a charge of insubordination, and the subsequent punishment made him a war casualty once again. He was admitted to a hospital in Warsaw with severe tonsillitis. After a full recovery, he was sent for further training and did not return to his former unit, the 352nd Division, until December 1943.

Hein was assigned to the 1st Artillery Battery as an orderly to Lieutenant Bernhard Frerking, a 32-year-old former teacher, with whom he immediately developed a good relationship. Frerking was an officer he could trust, and his loyalty was reciprocated. They were quartered together in a French mansion owned by the Legrand family in Houtteville, and he began to learn the language, largely thanks to Frerking, who was fluent in French. Despite being the embodiment of Nazi Germany, they did nothing to upset the locals, and Hein remained in contact with the Legrand family after the war.

The two soldiers reached WN 62 at 12:55 a.m. on June 6, and Frerking went directly to his observation post. A sergeant appeared with an ammunition box, and Severloh loaded his MG 42. Soldiers from the 726th Grenadier Regiment were also in position, and everyone waited for the first light of dawn. The bad weather obscured visibility, but as day broke, it was clear that the horizon was filled with ships of all sizes. Shortly after 6 a.m., bombers from the 8th U.S. Air Force appeared, prompting Hein and his comrades to take cover.

They were lucky. Poor visibility forced the planes to be cautious when dropping their bombs, and they landed harmlessly inland from the gun emplacements. Then the Allied warships opened fire with rockets and heavy shells. The size of the armada and the number of guns aimed at him made it clear to Hein that he would have to fight for his life that day, which meant taking out as many enemies as possible.

The first landing craft arrived within range around 6:30 a.m. They deployed their ramps and dropped off groups of GIs from the 1st U.S. Infantry Division, “The Big Red One”—not Tommies as expected—who, believing the Luftwaffe had eliminated most of the enemy, headed for the mainland.

The D-Day beaches had been precisely classified in the invasion plans to facilitate landings and advances inland, and the sector directly in front of and to the left of WN 62 was codenamed Easy Red. Directly to the right outside Severloh’s main firing line was the Fox Green sector.

Hein followed his order to wait until the troops were knee-deep in water and then open fire. This immediately caused panic and forced the survivors and wounded to seek cover behind the beach obstacles designed to hinder and damage the landing craft. Some found themselves hiding behind the bodies of dead comrades as they drifted ashore.

Further down, closer to the coast, there were problems with an MG 34, so Hein’s weapon did the most damage. (Sometime after the war, Hein met another rifleman from the 726th Regiment, Franz Glöckl, who was operating a pre-war Polish water-cooled machine gun. Franz was only 18 years old, even younger than Hein, but a hand injury put him out of action after a few hours.)

The first American troops, arriving at low tide, were about 450 meters away. As the tide rose, the subsequent attack waves came closer and closer and were therefore easier to hit. Each ramp fired revealed 30 potential targets, and a precise, short salvo of about three seconds was enough to decimate a platoon.

Given the rifle’s rate of fire, it was likely that if one bullet hit a target, more would follow. (After the war, Hein met an American soldier who had been hit three times while disembarking on the beach and was therefore almost certainly one of Hein’s victims.)

The calm between the waves allowed the MG 42’s barrel to cool somewhat, but it still required regular replacement. When it wasn’t ready for use, Hein simply used his Mauser K98 rifle, which he fired an estimated 400 times that day. He never lacked a target, as the strong west-to-east current drove many of the small landing craft further along the coast, away from their intended landing sites. This meant that even more of them stranded within range of Hein’s weapon.

Lieutenant Frerking and the rest of the team were almost exclusively occupied with identifying targets, establishing coordinates, and transmitting messages through the zigzag trenches so that the battery in Houtteville could do its work.

Severloh was understandably engrossed in his task, but as the morning wore on, he realized that his machine gun was the only one firing on that stretch of beach. (Many years later, he was able to consult the German military archives and discovered a report at 10:12 that morning that only one machine gun was in use at WN 62—his, of course. This also made him reflect on his personal responsibility for the many casualties on Easy Red.)

Severloh’s daily report recalled several waves of 10 to 15 landing craft heading toward his section of the beach and estimated that six of them arrived before noon. Along the entire length of Omaha Beach, each wave comprised a total of about 50 craft, a mix of wood-sided LCVPs with armored ramps and more heavily protected LCAs. When it became clear that each ramp drop would be followed by about 50 machine gun bursts, many soldiers abandoned the craft prematurely, often into water too deep for their heavily laden bodies.

Machine guns are most effective when fired at groups, especially in confined spaces. After the occupants of the landing craft were targeted in this way, the remaining crew members were killed by rifle fire. An incident that would haunt Hein Severloh for many years occurred when he switched to rifle fire.

Opposite the position of WN 62 on the beach today stand two concrete blocks. They originally belonged to a mill that crushed beach pebbles into material for bunker construction. An American survivor with a flamethrower strapped to his back tried to seek shelter behind these blocks, but Severloh shot him through the helmet. The individual drama of this event left a more lasting impression on him than the sight of the soldiers collapsing in large numbers under his machine gun fire, and he relived it repeatedly in his dreams after the war.

Around 2 p.m., further west, toward Exit E-1 at St. Laurent, Hein noticed several Sherman tanks moving toward his section of the beach. The main components of WN 65, guarding the St. Laurent exit, had been successfully disabled by late morning, and columns of American soldiers were climbing various parts of the cliff.

Hein had exhausted his 12,000 machine gun bullets and had to resort to less lethal tracer bullets. This risked revealing his position, especially to the American warships sailing closer to shore, taking advantage of the rising tide.

It wasn’t long before a grenade exploded in front of his position, leaving him with a painful facial injury. At 3:00 p.m., Lieutenant Frerking decided there was no choice but to abandon WN 62. Many soldiers of the 726th Regiment were already wounded or had retreated up the slopes, and his observation post had just suffered shell damage. It was time for the remaining soldiers of his team to leave the trench that offered them immediate protection.

Frerking ordered Hein to go out first and said he would follow. Severloh recalled this particularly poignant moment, as his officer addressed him informally, which would have violated the disciplinary code. He ran into the trench as fast as he could, armed with a loaded machine gun and an ammunition belt.

The first edition of Hein Severloh’s book “WN 62” was published in 2000, and the first English edition appeared in 2011. Until then, the most important information about the day’s events came from numerous American eyewitness accounts, which are still readily available and widely known today. Reading these accounts provides a good insight into what it was like to be exposed to an MG 42 and allows one to understand the gradual attacks from the beach that led to the base being virtually encircled.

At 6:30 a.m., LCVPs carrying troops from E and F Companies, 16th Infantry Regiment, 1st Infantry Division, arrived on the beach opposite the Colleville exit. E Company commander Captain Ed Wozenski reported that as soon as the men left their boats to wade ashore, they came under heavy machine gun fire and fell into the bloody water, until only a few reached the gravel shore.

They were followed by several LCVPs carrying men from the 116th Regiment, 29th Infantry Division, who were supposed to land much farther west but had been driven further east by currents and bad weather. For these men, their landing strategy was abandoned in favor of survival.

Within an hour, the headquarters company of the 1st Battalion, 16th Infantry Regiment, landed to the left of Easy Red, just below Severloh, under heavy automatic weapons fire, finding

survivors of the first attack waves stranded on the beach. A reserve regiment of the 18th Regiment, 1st Division, was scheduled to land before noon and sent a reconnaissance party early, but had to change its plan when it realized the intensity of fire from WN 62.

At the time, Hein didn’t know he was also shooting a celebrity. Robert Capa, one of the war’s most famous photojournalists, had been riding on an LCVP, and his exploits with the camera, which brought home some of the day’s most graphic images, were nearly interrupted by Private Severloh. Around 11 a.m., Ernest Hemingway, who was not granted a quiet retirement, approached Easy Red, but the pilot of his boat swerved to another part of the beach when he realized how dangerous a landing there would be.

In addition to the infantry, the first waves also included men from the 5th Special Engineer Brigade, who reported very heavy fire between Colleville and the nearest beach exit to the west at St. Laurent-sur-Mer (codenamed E-1). Severloh later confirmed this, mentioning that during a break between the waves, he saw a red flag placed beneath him in the sand by a survivor to guide subsequent landing craft.

At about the same time, several duplex-engined Sherman tanks arrived on the beach. One of them was able to disable two 75mm guns on the other side of the Colleville exit, allowing the troops to advance up the cliff. However, there was no movement away from the beach below Severloh, and by 8:00 a.m. the situation had become so critical that abandoning the attack on Omaha was quite possible.

However, observers peering through binoculars from ships offshore could see that small groups of men had begun climbing the cliffs further east in the areas of WN 61 and WN 60. Despite the difficulties at Omaha, they realized that the invasion plan was working. Hein learned only years later that his stubborn determination to prevent the crossing of the beach could have changed the course of events that day.

Of course, the mortar and artillery fire directed by WN 62 played a major role in the carnage in this sandy sector, but Hein also contributed indirectly by providing the covering fire that enabled his lieutenant and the rest of his team to do their job effectively and transmit the coordinates of these targets.

What Hein and his comrades didn’t know was that Captain Joe Dawson and a group from G Company, 16th Infantry Regiment, were already on the outskirts of the small town of Colleville, just inland at the top of the depression, at 1:15 p.m. During the course of the morning, Dawson had found a way over the cliffs to the west. Combined with the earlier advances on the other side of the depression, this meant that Frerking’s decision to withdraw at 3:00 p.m. came not a moment too soon. They were practically surrounded.

Hein’s escape route from WN 62 took the path of least resistance: trenches, craters, anything that helped him keep his head down. After a while, he turned into the ravine leading to the village of St. Laurent-sur-Mer and waited for the rest of his team. Only one appeared: radio operator Kurt Wernecke, who relayed the shocking news that everyone else, including Frerking, had been killed. A few minutes later, they themselves were caught in a machine gun salvo, suffering painful flesh wounds, but they managed to reach WN 63, where a medic provided first aid.

They recovered for a while, but around midnight, the entire group, including a wagon full of wounded and some American prisoners (one of whom happened to have German parents and spoke a familiar dialect), decided to move inland under cover of darkness. Shortly before dawn, they came under fire again, and it became clear they were surrounded. Reluctantly and ironically, they demanded that their own prisoners accept their surrender.

The GIs they captured belonged to the 16th Infantry Regiment, the main regiment Severloh’s machine gun had been firing on all morning. So he had to be very careful not to reveal too much information about himself.

One of the men captured at the same time was stationed at WN 61 on the other side of Colleville Draw and provided Hein with a graphic but discreet description of the damage his weapon had inflicted on the American troops. Below his position, invisible to him at the time, lay hundreds of corpses where the sea had left them.

Although wounded, Hein spent the next few days helping other prisoners of war at a makeshift camp in Vierville, at the other end of Omaha Beach. He was then shipped to England and from there to the United States to work in various camps along the East Coast, from Boston to Florida, primarily harvesting crops, including potatoes and cotton.

In his book, he recalls another incident that came to mind in light of the events of D-Day, when he and a friend discovered an old issue of Star magazine that contained a vivid description of a place he knew well: “Gunmen could not reach Easy Red beach because the bloody mass floating there was so high that the soldiers could not wade through and kept slipping.”

Severloh remained a prisoner of war after the war and was deported to Belgium in March 1946, then to England and Scotland. Hein was finally released in April 1947 after his elderly father asked him for help on the farm.

Hein did his best to adjust to rural life upon his return, but he couldn’t keep his war experiences buried in his mind forever. Many of them demanded closure, however difficult that might be.

First, he had to contact Lieutenant Frerking’s family. Two weeks after his arrival, his parents managed to arrange a visit from Frerking’s mother. Their son was still considered missing, but Hein was able to confirm his fate, as Karl Wernecke had reported to him.

He then sent a sketch of WN 62 to the Legrand family, with whom he was billeted, and asked if there were any traces of a grave there. Fernand Legrand was soon able to visit the site and discovered a wooden tombstone. After consulting with the authorities, he found Frerking’s trail to a cemetery built above the beach. (Several temporary cemeteries were established in the area, often containing both American and German dead. Eventually, in the late 1950s, the majority of the German remains were transferred to a cemetery in La Cambe, just a few kilometers south of Omaha Beach. This is Frerking’s final resting place.)

The most positive experience for Hein Severloh after his return was meeting Lisa, a girl he had met shortly before his transfer to France. They were able to continue where they left off in 1943 and eventually married in 1949. For a time, she was the only person he could talk to about the war, as he became very depressed, remorseful, and thoughtful.

The memory of the lone soldier with a flamethrower, whom he had shot with his rifle in the gravel mill on the beach, strangely affected him more than the carnage he had caused with his MG 42. He suffered from frequent sleep deprivation. He developed a strong opposition to the establishment and even joined the Association of Conscientious Objectors in Hanover.

Like many returning soldiers, Hein tried to forget the past, but he simply couldn’t ignore the popular 1959 magazine article titled “They’re Coming” by Paul Carell. Astonished that none of the articles mentioned his neighborhood of Omaha Beach, he contacted the author, who saw him as a valuable witness to the liberation and helped him connect with other comrades as the magazine evolved into a book (“Invasion – They’re Coming!”).

In 1961, Hein visited Normandy for the first time for the opening of the German military cemetery in La Cambe. He was accompanied by Frerking’s mother and widow. He also visited the site of WN 62, which was completely overgrown. (Today, the main features have been exposed, so the bunkers and trenches can still be recognized.)

He also met the Legrand family for the first time since D-Day and learned that Frerking had called them from his bunker at 7 a.m., warning them of the invasion and advising them to head for safety in Bayeux, ten kilometers away. He believed that both the Germans and the Allies would respect the town as a historical monument, making it less likely to be shelled or bombed.

This gesture underscored the relationship they maintained with the people whose homes and villages they had occupied. Although the Legrands were a respected local family, they took a risk with their friendship with the Germans, knowing (as it turned out, rightly so) how the French would treat collaborators.

Mr. Legrand then made Hein a surprising offer: He asked him, an experienced farmer, to take over his farm in Houtteville, as his only son had died young and he and his wife were already advanced in age. After careful consideration, Hein had to decline the offer for logistical reasons, but remained in contact with the Legrands until the end of his life.

Through his relationship with Paul Carell, Hein Severloh continually established new contacts. The most significant of these came when Paul presented Hein with the first edition of Cornelius Ryan’s “The Longest Day,” which would become the classic account of D-Day.

In it, Hein read the story of David Silva, who had come under heavy fire off Easy Red Beach near Colleville in the early afternoon. He was hit three times by a machine gun with tracer bullets, so there could only be one person responsible: Corporal Heinrich Severloh!

Hein was now on a mission. He learned that David Silva had become a priest and moved to Akron, Ohio, but his letters were returned due to frequent changes of address. He finally found him again in Karlsruhe, and it wasn’t long before the two veterans experienced an emotional and cathartic reunion, from which a lasting friendship and mutual respect grew.

Over the years, many more contacts with D-Day veterans were established. In 1984, Hein received a call from Franz Glöckl, an 18-year-old soldier from the 726th Grenadier Regiment, who had fired from a position directly below him.

Glöckl had organized a meeting with men from WNs 60, 61, 62, and 63 and invited him. This helped him close many gaps in his knowledge about the events of June 6, 1944, and support Hein in processing the trauma.

During one of his visits, he met Jack Borman, whose duplex-engined Sherman, he recalled, had become stuck in the gravel beneath him on the beach. His tank had destroyed one of the 75mm guns on WN 62, and Jack’s remorse for the losses he had caused was another reminder to Hein that war affects soldiers on both sides similarly.

As early as 1960, when Paul Carell’s book “Invasion – They’re Coming!” was published, Hein attracted the attention of many circles, especially authors and journalists. The most bizarre encounter, however, occurred in 1984, when an English reenactment group invited him to Great Britain. It called itself the “Association for the Restoration of the Honor of German Wehrmacht Soldiers.” Its members wore uniforms decorated with medals and badges and strictly adhered to military procedures with which Hein was all too familiar.

They even presented him with a medal, similar to the Purple Heart, which he was entitled to due to his injuries on D-Day. He politely accepted it and said his goodbyes. Completely bewildered, he wondered why anyone would want to reenact events that had caused him and so many others so much suffering.

Other authors, he felt, tried to sensationalize him and failed to emphasize the anti-war message he was trying to convey. He also received offers for several documentaries and interview requests from French and German magazines. Despite his efforts to maintain control, he found that journalists were only too willing to put words in his mouth and ask leading questions.

At the end of a 40th anniversary interview with the American broadcaster ABC in 1984, he was repeatedly asked on camera how many men he had killed. Since he refused to answer, he was given the number 1,000. Perhaps at the end of the interview, he admitted that this was likely and that it might have been twice as many. This admission gave him some relief, but also brought him the notoriety that brought him even more attention from journalists, authors, and filmmakers.

In 1999, he was contacted by Helmut Konrad Baron von Keusgen, a leading D-Day author. Hein quickly recognized Hein’s crucial role on that day and offered to help him write his personal account. Thus began a friendship that enabled Hein to process the trauma he suffered 55 years after D-Day. This friendship ultimately led to the book WN 62, which tells the full story.

Unsurprisingly, this sparked further interest from journalists and filmmakers. But it wasn’t until an invitation to appear in a film in 2003 that everything came to a head. Hein was led to the beach below WN 62 and asked to continue along the shore toward another man. As they approached, he realized it was David Silva, the man who had taken three bullets from his gun on D-Day, whom Hein had tracked down after discovering his account in “The Longest Day.” Thirty-nine years had passed since their first meeting.

Hein and David spent four emotionally charged days filming together, reliving the events that had brought them together and sharing stories about everything that had happened since. A visit to the American cemetery near WN 62 was particularly taxing on their emotional reserves, and both decided that this would be their last trip to Normandy, which indirectly meant they would never see each other again in this lifetime. Hein’s health finally failed in 2006. David lived until 2010.

Hein Severloh’s assessment of the carnage he caused on D-Day was based on his own observation of the stretch of beach below his firing position and on what he learned from other soldiers he met some time later, who saw piles of bodies in his line of fire, some of which may have drifted along the shore. This assessment was reinforced by media reports that may have exaggerated his contribution to the casualty count. Only relatively recently have the figures been analyzed in detail.

In his very detailed report on Omaha Beach (2004), Joe Balkoski estimates the total number of US losses (dead, wounded, missing) on D-Day at around 4,700. To understand Hein Severloh’s role in this latter enumeration, it is important to consider the entire defense.

The beach was protected by 15 resistance nest bunkers and large-caliber guns positioned further inland. Severloh himself stated that 85 machine guns were positioned along the beach, although not all of them were operational that day.

In addition to German weapons, there were also natural disasters that claimed lives. In the English Channel, many crew members of Sherman tanks with duplex propulsion were killed after unsuccessful launches off the coast. Infantrymen who jumped from landing craft into deep water before the ramps were lowered to avoid heavy fire also drowned.

Omaha Beach is more than six kilometers long. The 29th Infantry Division landed in the western half, although weather and currents carried some of its 116th Infantry Boats to Easy Red. The 29th Division suffered approximately 1,350 casualties. The 1st Division, which landed in the eastern half, stretching from a point west of WN 65 to below WN 60, suffered only 70 fewer casualties. The remaining units, mostly engineers, that landed along the entire beach, completed the casualty list.

Even a quick glance at the casualty figures makes it clear that only a small fraction of them could have fallen into Severloh’s sights. Those who survived may also have fallen victim to grenades, mortar shells, and various machine gun and rifle fire. Further investigations, in my opinion, would be a purely academic exercise and would neither preserve the memory of the men whose lives ended brutally on D-Day nor enrich the scholarship of history.

Nevertheless, it is probably fair to say that without the intervention of Private Heinrich Severloh, the US Army would have been about one battalion stronger during the withdrawal from the bridgehead in Normandy.

The notoriety Severloh later achieved, earning him the title “The Beast of Omaha,” was largely his own doing. He could have returned home and picked up where he left off, in his local farming community, keeping his thoughts to himself. But his curiosity and conscience prevailed, leading him down a path that repeatedly confronted him with the most shocking and horrific day of his life.

From his writings and the numerous interviews we can easily access online today, there is no indication that he attempted to glorify what had happened. He doesn’t seem to be trying to portray himself as another war victim or beg for sympathy. By revealing his guilt, he took many risks and may have encountered others during his regular visits to Normandy who still sought revenge.

He would have preferred to forget Hein’s contribution to World War II. But he couldn’t. Instead, he chose to reveal it to the world so that we would all be aware of the consequences when one country declares war on another. In doing so, he challenges us to seek better solutions to conflicts when we cannot justify such a thing happening again.