The Classification System at Ravensbrück: Understanding the Camp’s Identification Marks _usr1

At Ravensbrück, the largest Nazi concentration camp for women, the striped uniforms served as part of a structured identification system in which colored triangles and fabric numbers were pinned or sewn onto the clothing. These markings assigned each prisoner to an administrative category and reflected the visual organization used across the camp system. A photograph showing a woman in a striped uniform standing before an SS officer illustrates how these codes functioned: each badge indicated the reason for imprisonment, while the uniform itself became part of the camp’s regulatory framework.

The Nazi Classification System

The colored triangles followed a strict coding structure.

– Red identified political prisoners, including many members of the French Resistance.

– Green indicated individuals classified as habitual offenders.

– Yellow, often combined with a second triangle forming the Star of David, marked Jewish prisoners.

– Black was used for those labeled “asocial,” including groups targeted by discriminatory policies.

At Ravensbrück, located near Fürstenberg about 90 km north of Berlin, these insignia were sewn onto the left side of the uniform, along with an identification number stitched onto the sleeve. This system enabled camp authorities to organize labor assignments and maintain administrative oversight.

Everyday Life in the Camp Blocks

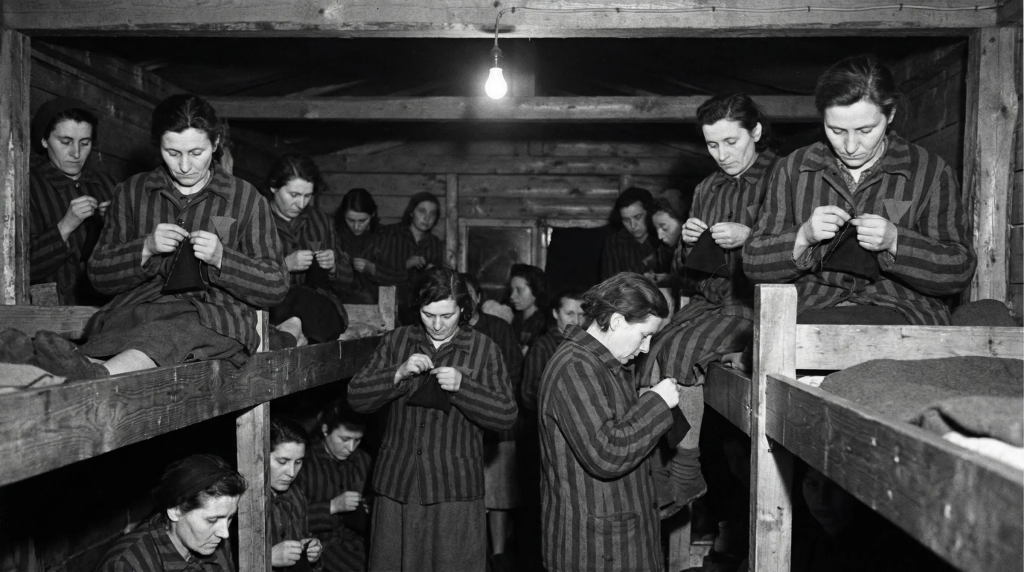

Inside the crowded barracks, prisoners often sewed these symbols onto their own uniforms under limited lighting. The striped garments, usually worn and uncomfortable, became part of daily life during long work hours in armament workshops or in external work details such as the Holleischen commandos. Despite the strict regulations, some prisoners supported one another by adjusting uniforms or sharing small resources to maintain morale. SS personnel assigned to Ravensbrück supervised these procedures and enforced the camp’s uniform requirements.

Testimonies and Acts of Solidarity

Ethnologist and resistance member Germaine Tillion wrote about how these classification symbols shaped relationships inside the camp, sometimes creating divisions and at other times encouraging cooperation. Many women formed networks of mutual assistance, exchanging knowledge or providing discreet emotional support. Although Ravensbrück witnessed extremely harsh conditions and high mortality, these personal accounts highlight moments of collective strength and resilience.

After the liberation of the camp by the Red Army in April 1945, many survivors shared their testimonies, helping historians understand how the classification system influenced daily life and social dynamics.

Legacy and Collective Memory

Today, institutions such as the Ravensbrück Memorial and archival websites like www.orte-der-erinnerung.de preserve these uniforms and insignia as historical artifacts. They demonstrate how a visual and bureaucratic system was used to organize and control populations within the camps.

Post-war trials, including those held in Hamburg in 1946–1947, featured testimonies from Ravensbrück survivors, contributing to a clearer understanding of the camp’s administrative structures. Over time, some of the symbols used in the classification system—especially the red triangle—have been reclaimed as emblems of antifascist remembrance.

This identification system, used at Ravensbrück until 1945, remains an important subject of historical study, illustrating how administrative tools can deeply shape the lives and experiences of individuals under oppressive regimes.