Keir Starmer meets Georgia Meloni (Image: Getty)

TABLE OF CONTENT

- The countries where it’s working

- Countries performing dizzying u-turns

- Countries failing to keep up

While Reform UK may be dominating the migrant debate in Britain, Nigel Farage is not a unique politician for a continent growing rapidly angrier at the political establishment. Like with Labour’s election win last year, numerous countries across Europe are seeing the last stand of a brand of politics that has lost trust with voters.

Some countries, like Denmark and Italy, have already fallen to governments willing to prioritise populist anti-migrant politics. Others, like Germany, have seen centrist governments forced to tack right in a last-ditch effort to maintain their grasp on power and avoid voters turning to more extreme options at the ballot box. Keir Starmer hopes that by working with Europe he can come up with a solution to reduce Reform’s popularity, but voters increasingly appear to be turning away from the idea of cross-border collaboration and towards more selfish radicalism.

What exactly is each major country doing to curb the tide of both immigration and radicalism from voters? The Times has put together a useful summary.

Starmer may want to look to how other countries are, or are not, dealing with migration (Image: Getty)

The countries where it’s working

Denmark

Denmark is an outlier in northern western Europe, as one of the countries to have turned against mass immigration and liberal multiculturalism more than a decade ago.

As a result its Social Democrats centre-left party is not just in power, but well ahead of all other parties including populist alternatives.

Among the country’s official policies include an objective to reduce the number of asylum claims to zero, revoking asylum status when the individuals country is once again deemed “safe”, and very tough rules around family reunification.

The country also has a radical policy to prevent ‘ghettos’ of ethnic minorities building up, including forcible relocation when estate demographics become unbalanced, or even demolition.

Only the Tories’ Kemi Badenoch has floated this last policy as a potential option.

Italy

Italy has become a byword for government by right-wing populism, since Donald Trump’s best friend, Georgia Meloni, took power in 2023.

While migrant arrivals into Italy are up 9% in the first seven months of this year, acceptance rates are less than 10%, meaning many flow up into northern Europe, reducing pressure on Italy.

Australia

While not in Europe, Nigel Farage has long cited Australia as the textbook example of how to stop the boats.

In 2013, Australia saw 20,000 enter via small boats from Indonesia, Iran and Sri Lanka, before a conservative government led by Tony Abbott instigated “Operation Sovereign Borders”, picking up small boats and taking them to overseas island detention centres.

While human rights groups shrieked and shouted, it led to a collapse in attempted crossings.

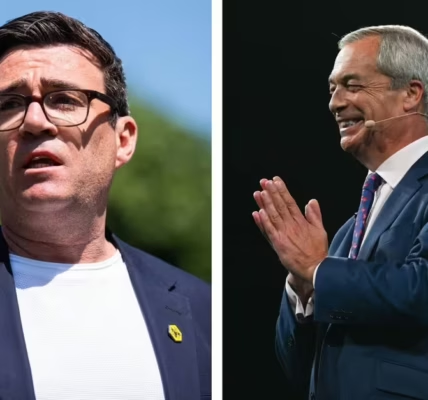

Nigel Farage’s illegal migrant policy has grabbed the political limelight (Image: Getty)

Countries performing dizzying u-turns

Germany

Germany’s change in policy towards asylum seekers has been jaw-droppingly quick and brutal.

In 2015 Angela Merkel foolishly opened the floodgates to more than one million asylum seekers, promoted with a now-infamous slogan “We Can Do It!”

Public anger was swift, often in response to terrorist and sexual assault incidents perpetrated by those let in by Ms Merkel, and Germany now has one of the most hardline right-wing parties in Europe – the AfD – topping its opinion polls.

Her centre-right successor, Friedrich Merz, has introduced much stricter border laws to turn away virtually all asylum seekers.

Many asylum seekers are now barred from bringing their family members to Germany, and they’ve had their benefits replaced with prepaid cards to control what they can purchase.

Germany is also leading the way in returns to Afghanistan, with over 80 illegal migrants being flown back to the Taliban – a policy Reform UK now ape.

Sweden

For decades Sweden had one of the most liberal and open immigration policies in Europe. During the 2015 migration crisis, it took in more asylum seekers per capita than any other country.

However the huge social and economic strains inflicted on native Swedes, not least a shocking rise in gun fatalities, has sparked damning political reprisals.

The Swedish Democrats, Reform’s equivalent, has surged to a comfortable second place in the opinion polls, while asylum acceptance rates have been reduced to the minimum allowed by EU law.

Roughly half of illegal migrants return to their native country voluntarily, while the government has powers to order those destined for forcible deportation to live in bespoke facilities or put electronic tabs on them.

Countries failing to keep up

France

France has a whopping 800,000 illegal migrants, and managed to deport just 21,607 last year.

The country is being prevented from more action due to Algeria’s refusal to accept criminal returns, with the number of asylum applications rising by 80% between 2020 and 2023.

The country’s constitutional court has overturned attempts to introduce more hardline policies, including crackdowns on immigrants bringing their families to the country and accessing benefits.

Emmanuel Macron’s party, Renaissance, is massively behind the polls, while Marine Le Pen’s Front National is well out in front.

Spain

In November last year the Spanish government announced it will legalise around 300,000 undocumented migrants per year through 2027, in an effort to boost economic growth.

With 600,000 illegal migrants, Spain has one of the highest rates in the EU.

It also introduced more legal routes for asylum seekers.

Netherlands

Immigration has caused the collapse of two Dutch governments in a row, largely thanks to the right-wing Freedom Party led by Geert Wilders.

He collapsed the coalition in June, after the EU and human rights laws were blamed with preventing him meeting his promise to introduce the “toughest asylum policy ever”.

His hard-right party still leads in the opinion polls.

First time applicants are now, however, at their lowest level in three years, at just 2,000 a month.