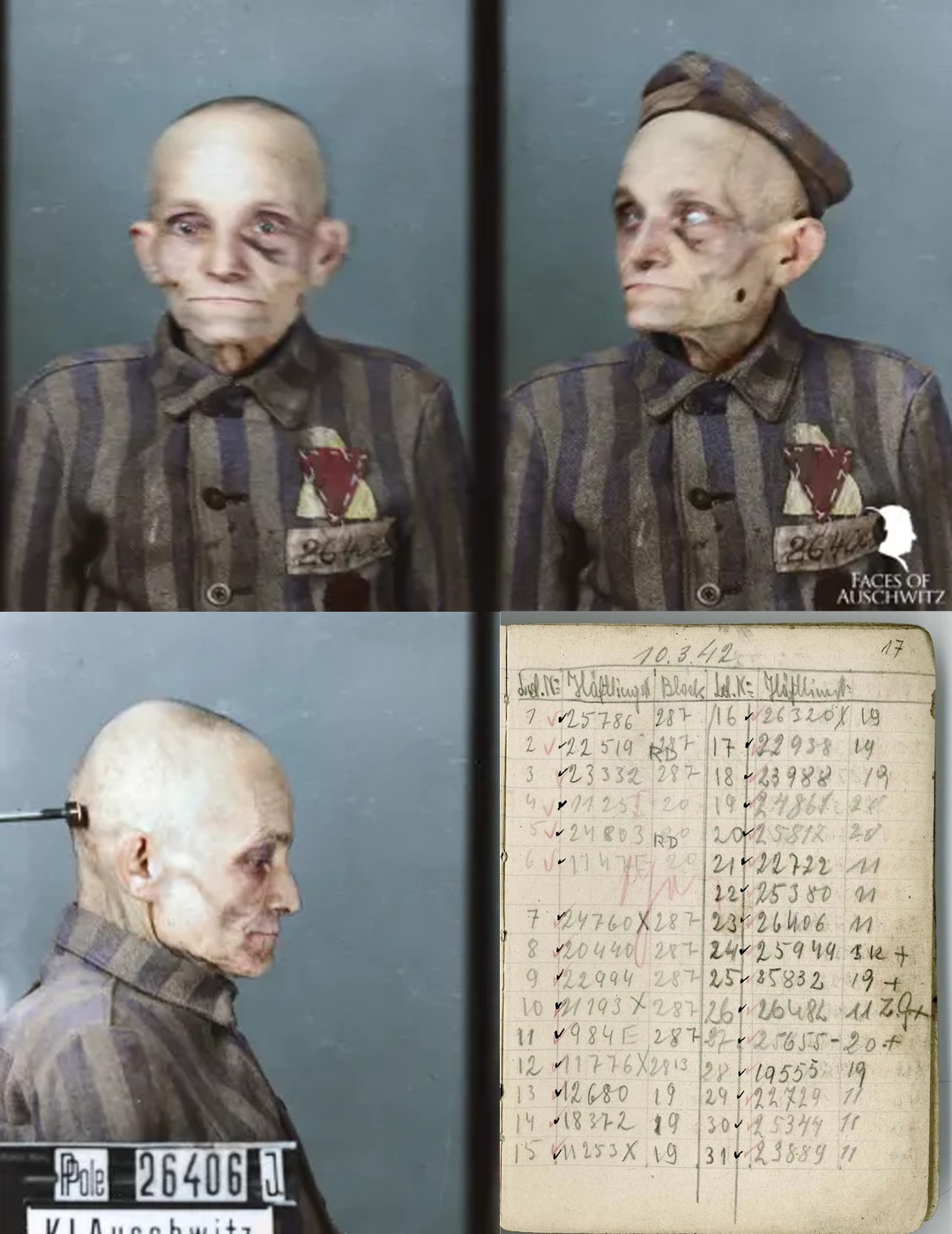

“Before there was a number, there was a name: Aron Löwi.

Five days in Auschwitz and a photograph that survived his tormentors.

To remember is to resist.”

Who was Aron Löwi?

Aron Löwi was a Jewish merchant from Zator , a small town in Poland. On March 5, 1942, his name was reduced to a number: 26406. Transferred from the prison in Tarnów to Auschwitz, he was 62 years old—old enough to have known a full life, young enough to still hope for peace. He died five days later , on March 10, 1942 .

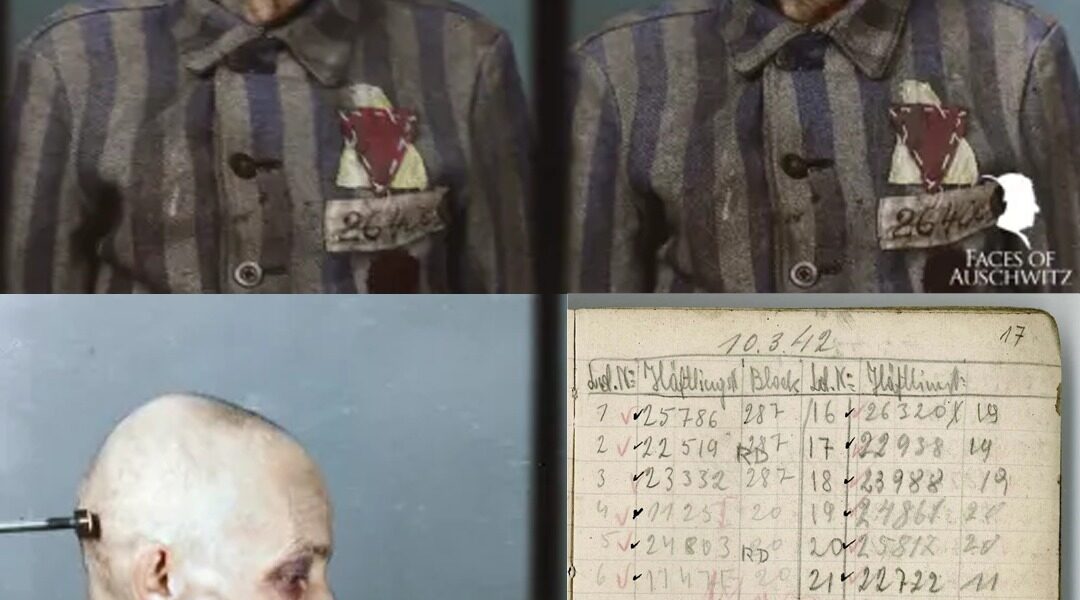

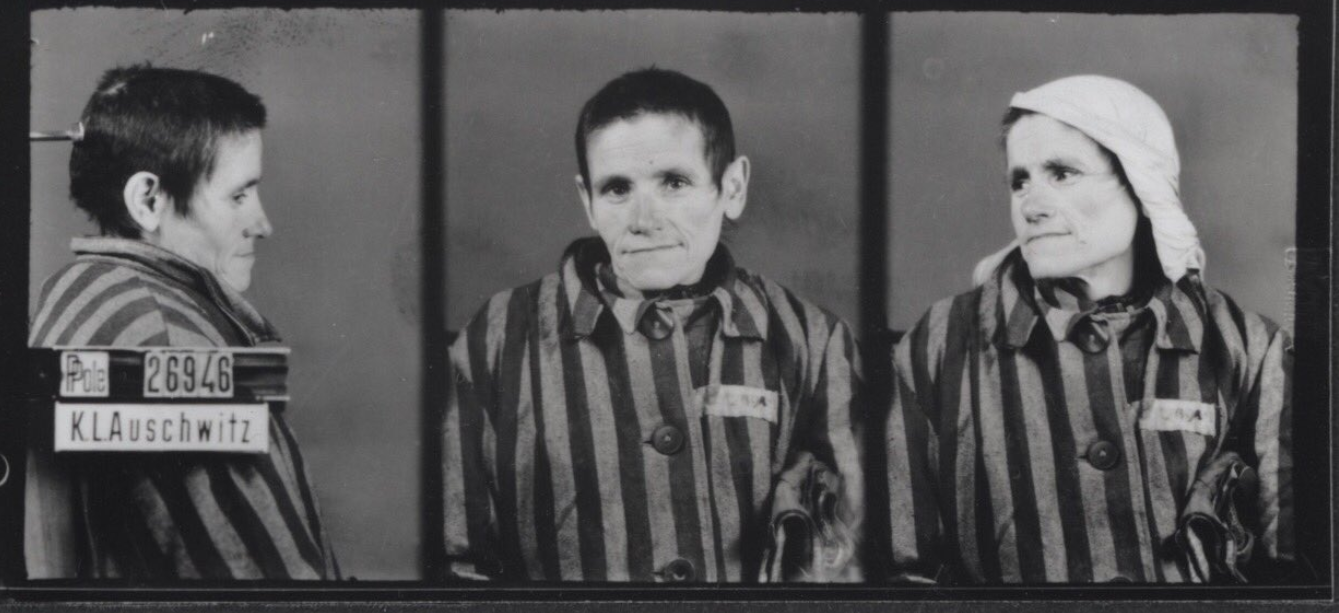

What the photographs reveal:

The three portraits (frontal, profile, and three-quarter view) follow the protocol of the camp’s identification service. Aron

‘s striped jacket bears the triangular badges prescribed by the SS.

- Yellow to mark Jewish identity ;

- Red for the category “political” .

In many cases, these triangles were superimposed to create a two-colored six-pointed star — a system that depersonalized and classified prisoners through colors and categories .

In his sunken eyes, in the still-visible bruises, we read disbelief , exhaustion , and that form of silent resistance in the face of the unimaginable. The photographs were taken at the moment when heads were shaved, personal belongings confiscated, and a name replaced by a number .

Five days, a single line in the register.

A register page dated March 10, 1942 , documents the administrative registration of Aron Löwi . As with so many others: no grave, no farewell —just a brief line in a notebook and a few photographs. Early deaths—often within the first week—were frequent: hunger, cold, disease, violence .

Portraits as evidence — and as restitution.

The Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum preserves tens of thousands of registration photographs today — only a fraction of the total collection destroyed during the Nazi retreat. Restoration and contextualization projects like Faces of Auschwitz give back a face, a biography, a voice to those whom the bureaucracy of murder had reduced to codes .

These images are legally admissible evidence , but also moral dialogues : they compel us to look, to name, and to recognize the person behind the striped uniform. Every time we utter the name Aron Löwi , the machine that claimed to be able to erase him fails anew .

Why look any further?

Because photography has outlived those who took it .

Because memory lasts longer than hatred .

Because remembrance is a form of resistance —a way to give Aron Löwi and so many others back what was violently taken from them: their humanity .