THE LAST WHISPER OF THE WHITE ROSE: The cursed prophecy that Sophie Scholl hissed at her executioners shortly before the noose silenced her forever _de85

CONTENT WARNING: This article describes the arrest, trial, and execution of a young woman by the Nazi regime—content that may be deeply disturbing. The article aims to provide historical information about civil courage and nonviolent resistance, and to encourage reflection on conscience and human dignity.

Munich, February 22, 1943: The 21-year-old student who faced the guillotine with a glimmer of hope – “Such a radiant sun is rising… we will see each other again.”

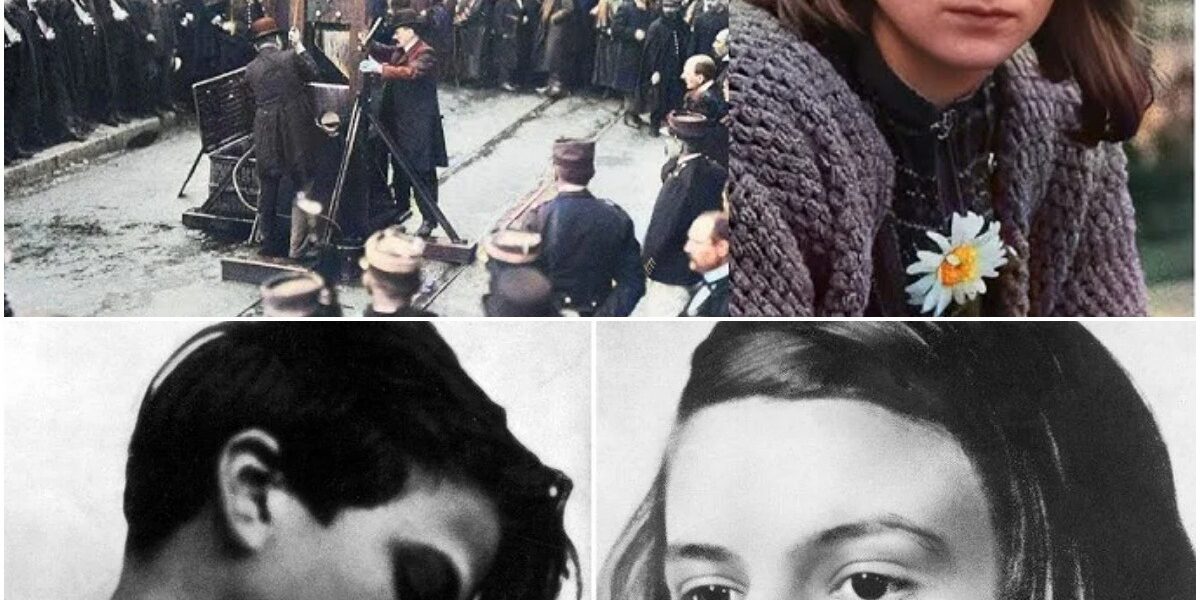

In the heart of Nazi Germany, where silence had become a means of survival, a 21-year-old biology student decided to raise her voice. On a February morning in 1943 , Sophie Scholl , with a calm gaze and unwavering conviction, distributed leaflets in the atrium of the University of Munich. Minutes later, a janitor’s whistle shattered the silence. The Gestapo was approaching. Within four days, Sophie, her brother Hans, and her friend Christoph Probst would stand before the notorious judge Roland Freisler , receive their death sentences, and be executed by guillotine at Stadelheim Prison .

But in those final hours, Sophie did not tremble. She gazed at the blade and saw the dawn. ” Such a radiant sun is rising… we will meet again ,” she whispered—words that slipped from the executioner’s lips and echoed into eternity.

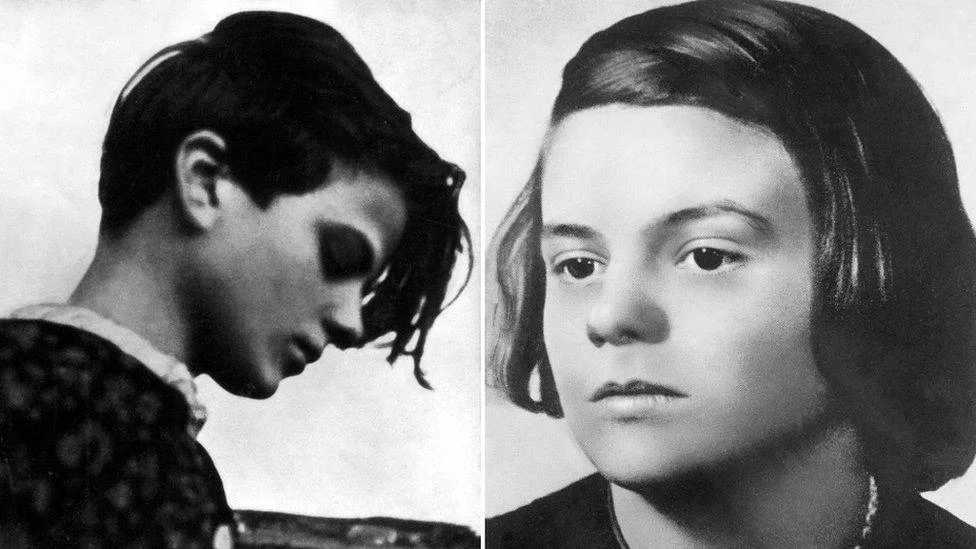

Sophie was born on May 9, 1921 , in the small town of Forchtenberg and grew up in a Lutheran home where compassion was a core tenet of their faith and justice a daily prayer. Like millions of German children, she once wore the uniform of the League of German Girls ; her early idealism was directed toward the promises of the regime. But by the end of the 1930s, these promises had turned into persecution. The pogroms of the Reichspogroms, the yellow stars, the disappearances—all of this undermined her faith in the Reich.

When Sophie arrived at the University of Munich in the spring of 1942 to study biology and philosophy, she was no longer a follower. She was a seeker. Here, in late-night discussions, stimulated by banned books and smuggled BBC broadcasts, she and her brother Hans – a medical student – founded the White Rose resistance group. With friends like Christoph Probst , Willi Graf , and Alexander Schmorell , they turned words into weapons.

Her leaflets were not calls to arms, but appeals to conscience. Secretly printed on a hand-operated duplicating machine, they condemned the murder of the Jews, the carnage on the Eastern Front, and the moral decay of a nation. “ We will not be silent ,” one read. “ We are your bad conscience. The White Rose will not leave you in peace! ” Sophie wrote with the clarity of a poet and the urgency of a prophet, placing copies in mailboxes, distributing them in lecture halls, and sending them to professors and priests throughout the Reich.

The Gestapo was hunting shadows. On February 18, 1943, Sophie and Hans dared their boldest act. While students streamed between lectures, the siblings climbed the marble staircase of the university’s main building and threw hundreds of leaflets into the air. They floated to the ground like white petals of truth. A janitor, loyal to the regime, saw them. The trap snapped shut.

For four days, Sophie was interrogated by the Gestapo at Wittelsbach Castle, including by Robert Mohr , an experienced investigator. When she was offered the chance to save herself by denouncing her comrades, she refused. ” I would do it again ,” she said. Mohr later admitted that he had never seen such a composed prisoner condemned to death.

The trial on February 22nd descended into a farce, orchestrated by Roland Freisler , the shouting president of the People’s Court. Clad in blood-red robes, he hurled insults and threats. Sophie stood upright. ” You know as well as we do that the war is lost ,” she told him. ” Why are you so cowardly that you won’t admit it? ” Silence fell over the courtroom. Freisler sentenced all three to death.

That same afternoon, the guillotine awaited at Stadelheim Prison . Hans went first and cried, ” Long live freedom! ” as the blade fell. Christoph followed. Then Sophie. According to the prison chaplain, she walked to her death without trembling. She spoke her last words to the executioner—softly, firmly, radiantly: ” Such a radiant sun is rising… we will meet again. ” The blade fell. The sun continued to rise.

Sophie’s leaflets, smuggled out by a sympathetic guard, reached Allied radio stations and inspired resistance groups from Norway to Greece. After the war, her diary and letters became sacred texts of moral courage. Post-war Germany honored her with schools, streets, and squares bearing her name. The 2005 film ” Sophie Scholl: The Final Days” introduced her story to new generations.

What made Sophie so extraordinary was not her fearlessness—in her letters she admitted her fear—but that she acted despite this fear. She believed the human spirit could overcome any regime. Her last whisper was not a defeat, but a promise: a world in which conscience triumphs, in which the sun she saw rise would one day shine upon a finally free Germany—and a finally free humanity.

Sophie Scholl’s life raises a question that still burns within us: What would we do in her place?

Her answer, sealed in blood and light, is: Speak out. Resist. Hope.

And when the blade falls, whisper to the future: “We will meet again.”