THE MINSK EXECUTION CASE: The legend of Masha Bruskina – the 17-year-old heroine, tortured and executed with a slanderous sign reading “We are partisans” _de108

In the grim autumn of 1941, as the Nazi war machine raged through the Soviet Union, the occupied city of Minsk became the scene of one of the first public spectacles of terror intended to break resistance. On October 26, three people—two men and a young woman—were paraded through the streets, their necks weighted with placards bearing a lie in German and Russian: “We are partisans who fired on German troops.” The woman, barely 17 years old, was Masha Bruskina, a Jewish nurse whose silent resistance had already branded her a threat. What the Nazis had intended as a warning to the population instead became a legend: a story of unwavering courage that resonates in the Holocaust, the Nuremberg Trials, and modern memorials. This is the story of the Minsk execution trial, in which a young heroine transformed brutality into an enduring symbol of resistance.

A youth forged in revolution

Maria Borisovna Bruskina – known to all as Masha – was born on July 31, 1924, in Minsk, in the heart of Soviet Belarus. Raised in a Jewish family by her mother, Lucia Moiseyevna Bugakova, a senior editor at the Belarusian State Publishing House, Masha was steeped in the ideals of the Bolshevik Revolution from an early age. An avid reader and straight-A student, she was a proud member of the Komsomol and the Vladimir Lenin Pioneer Organization, embodying the communist zeal of her generation. As early as 1938, at just 14 years old, she was profiled in the newspaper “Pioneer of Belarus” as an exemplary eighth-grader whose face radiated the promise of a bright socialist future.

After graduating from Minsk Secondary School No. 28 in June 1941, Masha’s world collapsed just weeks later with Operation Barbarossa. The Nazi invasion of Belarus transformed the city into a cauldron of occupation and ghettoization. The Jewish population of Minsk, including Masha’s family, was forced into the Minsk Ghetto—a harbinger of annihilation. But amidst the chaos, Masha refused to become a victim. She volunteered as a nurse in a makeshift hospital at the Minsk Polytechnic Institute and cared for wounded Red Army soldiers who had been left behind during the retreat.

Here, in the sterile, swastika-draped hospital wards, Masha’s secret life began. Disguised as a dutiful nurse, she smuggled civilian clothes and forged identity papers to Soviet prisoners of war and wounded fighters, enabling them to escape certain death or deportation to labor camps. She coordinated with a local underground network of communists and partisans, delivering messages and supplies right under the noses of the German guards and their Lithuanian collaborators. Masha’s youth and her inconspicuous role as a nurse made her an ideal agent—she blended seamlessly into civilian life in the occupied territory, much like her contemporary Sina Portnova, the teenage cook who became a partisan and was executed a year later in Belarus. Both girls, barely out of childhood, operated in everyday disguise while simultaneously fueling Soviet resistance. Their executions mark the gruesome end to the suffering of an entire generation.

Betrayal and the shadow of the Gestapo

Mascha’s happiness was short-lived: On October 14, 1941, just three months after the occupation began, she was devastated. Betrayed by the captured Red Army soldier Boris Mikhailovich Rudzianko—who would later be involved in the mass murder of Minsk’s Jews—she was arrested along with eleven other resistance fighters by the Wehrmacht’s 707th Infantry Division and Lithuanian auxiliary troops of the 2nd Schutzmannschaft Battalion under the command of the notorious Major Antanas Impulevičius. Taken to a Gestapo prison, Mascha endured days of brutal torture: beatings, starvation, and psychological torment designed to break her will and extract her names. But the girl, who as a child had memorized Marxist texts, remained steadfast. She revealed nothing; her silence was a final act of loyalty to the cause.

On October 20, Masha smuggled a poignant letter from her cell to her mother in the ghetto—a fragile spark of humanity amidst the horror: “I am so worried that I have caused you so much distress. Don’t worry. Nothing bad has happened to me. I promise you that you will not have any further trouble because of me. If you can, please send me my dress, my green blouse, and my white socks. I want to be decently dressed when I leave here.” The words, written with a childlike concern for appearances, concealed the certainty of death. It was her last message, a testament to her composure, even as the gallows drew ever closer.

The public spectacle: Despite the noose

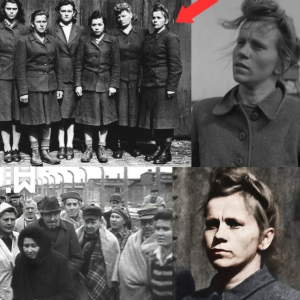

The Nazis, eager to spread fear and terror after the first partisan skirmishes, selected Masha and two of her comrades for a public execution—the first of its kind in occupied Soviet territory. Her fellow condemned men were 16-year-old Volodya Shcherbatsevich, also a Komsomol member, and Kirill Ivanovich Trus, a battle-hardened World War I veteran who had joined the resistance. On October 26, they were paraded through the streets of Minsk like criminals in a medieval morality play, signs around their necks proclaiming their “guilt” as partisans for daring to fire on German troops. For Masha, this label was a cruel slander; she had never held a weapon, her weapons were thread, ink, and her unwavering will.

The funeral procession ended in front of the gates of the Kristall Yeast Brewery on Oktyabrskaya Street (now a memorial site). A crowd of forced onlookers—workers, ghetto residents, and collaborators—watched as the three women were placed on stools beneath hastily erected gallows. Eyewitness Pyotr Pavlovich Borisenko later recalled the moment that gave rise to Masha’s legend: “When they put her on the stool, the girl turned her face toward the fence. The executioners wanted her to face the crowd, but she turned away, and that was that. No matter how much they pushed her and tried to turn her around, she kept her back to the crowd. Only then did they kick the stool out from under her feet.”

With this simple act, Mascha thwarted the Nazis’ staged subjugation. For three days, her body hung as a grotesque reminder until, on October 28, two Jewish prisoners were forced to take it down and transport it away on a truck. On the same day, ten other resistance fighters, including Volodya’s mother Olga, met the same fate nearby—a chain of executions that would reverberate throughout the city.

From “unknown girl” to eternal heroine

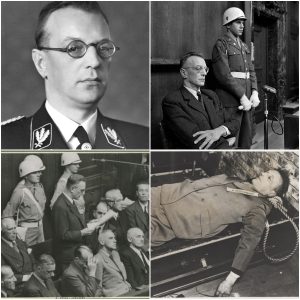

The photographs of the execution, taken by German soldiers as propaganda trophies, had a devastating effect. Smuggled out of the country and stored, they served as incriminating evidence at the Nuremberg Trials, revealing the barbarity of the Nazis to the world. Yet in the Soviet Union, Masha’s story was forgotten for decades. In official accounts, she was referred to simply as “the unknown girl,” and her Jewish heritage likely contributed to antisemitic neglect by the postwar authorities. It was only in the 1960s, thanks to the tireless journalistic efforts of figures like Vladimir Friedin and Lev Kotlyar, that her identity was fully restored. In 1970, she was posthumously awarded the title of Hero of the Soviet Union, and a memorial plaque was erected at the execution site, updated in 2009 to include her name.

Masha’s legend lives on worldwide to this day. In HaKfar HaYarok, Israel, there is a monument, and a street in Jerusalem bears her name. Documentaries, books, and articles—from the archives of the US Holocaust Memorial Museum to current YouTube videos—keep her memory alive. Like Zina Portnova, whose story of youthful resistance ended with a public execution, Masha embodies the quiet ferocity of those who fought not with bullets, but with borrowed shirts and stolen hours. The Minsk execution trial was meant to silence her; instead, it amplified a voice that still defiantly confronts tyrants everywhere.

In the words of a survivor who knew her: Masha didn’t simply die – she chose her path to eternity, her back turned to the horror, her gaze fixed on freedom. Her legend is not a myth; it is the irrefutable truth of a 17-year-old who made monsters tremble.