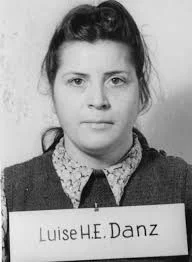

THE MONSTER WITH AN INNOCENT FACE: The Nazi Guard Who Killed 15,000 Women with Unimaginable Cruelty

In the annals of World War II’s darkest chapters, the Holocaust stands as a monument to human cruelty, where monsters walked among us in human form. While infamous figures like Irma Grese, the “Beautiful Beast,” and Maria Mandel, the “Queen of Auschwitz,” reveled in overt sadism, there was another whose terror was far more insidious—a silent architect of death who wielded her power not with screams or spectacles, but with the stroke of a pen. Meet Luise Danz: born on December 11, 1917, in a quiet corner of Germany, she would become one of the SS’s most elusive overseers, supervising horrors in camps like Kraków-Plaszów, Birkenau, Auschwitz, and Mauthausen. Unlike her flashy counterparts, Danz’s method was chillingly bureaucratic: reports that funneled thousands into gas chambers, all while she inflicted personal cruelties in the shadows. Her story isn’t just one of evil—it’s a stark reminder of how ordinary people can enable genocide through quiet complicity. As we delve into her life, prepare to confront a legacy that whispers louder than any shout.

Luise Danz’s descent into darkness began in her mid-20s, a time when many young women were dreaming of families or careers, but Danz chose the path of the Third Reich. At 26, in 1943, she joined the SS, the Nazi party’s elite paramilitary force, and was quickly thrust into the machinery of the Holocaust as an Aufseherin—a female overseer in the concentration camps. Her assignments read like a roadmap of hell: starting at Kraków-Plaszów in occupied Poland, where she monitored Jewish forced laborers under the brutal command of Amon Göth (the real-life inspiration for Schindler’s List). From there, she moved to the infamous Auschwitz complex, including its subcamp Birkenau, the epicenter of industrialized murder, and later to Mauthausen in Austria, a quarry camp notorious for its “Stairway of Death” that broke the bodies of countless prisoners.

What set Danz apart from the more theatrical killers like Grese—who delighted in public whippings and shootings—or Mandel, who orchestrated medical experiments with a cold detachment—was her preference for subtlety. Eyewitness accounts from survivors paint a portrait of a woman who avoided the spotlight, yet her impact was devastating. Rather than dirty her hands with direct executions, Danz excelled in the art of the “recommendation.” As a senior overseer, she compiled meticulous reports on “undesirable” inmates—often women and children deemed too weak for labor—and forwarded them to camp commandants with suggestions for “special treatment.” In Nazi euphemism, that meant the gas chambers. Historians estimate her reports contributed to the deaths of at least 15,000 female prisoners, a number that emerged only after Allied forces liberated the camps and sifted through the Nazis’ own damning paperwork. It was a form of killing by proxy: clean, efficient, and deniable. “She was the ghost in the files,” one survivor later testified, “deciding fates without ever facing her victims.”

But Danz wasn’t entirely hands-off. When her bureaucratic facade cracked, her cruelty turned visceral and petty, a twisted outlet for the power she craved. Survivors recounted her fondness for the bullwhip made of cow sinew—a flexible, lacerating tool that left prisoners’ backs in bloody ribbons. She patrolled the barracks with it coiled at her side, striking out at the slightest infraction: a slow worker, a whispered conversation, or even a defiant glance. One particularly harrowing testimony came from a Polish Jewish woman who endured Danz’s “winter punishments” at Birkenau. In the subzero nights of 1944, with temperatures plunging to -10°C (-14°F), Danz would order non-compliant inmates to strip naked and lie in the snow for hours. “They froze like statues,” the witness recalled, “their bodies turning blue as she watched with a smile, sipping hot coffee.” These acts weren’t just sadism; they were psychological warfare, breaking spirits before bodies gave out. Unlike Grese’s flamboyant brutality, Danz’s was intimate, almost maternal in its deception—she’d feign concern before unleashing hell, making her betrayals cut deeper.

The war’s end in 1945 brought a reckoning, but not immediately. As Soviet and Allied troops stormed the camps, Danz slipped away, blending into the chaos of defeated Germany. It wasn’t until June 1, 1945, that British forces captured her in a routine sweep, her SS uniform traded for civilian rags. The evidence against her piled up like the ashes in Auschwitz’s crematoria: seized documents from the camps revealed her signature on death lists, corroborated by a chorus of survivor testimonies. At her trial in 1947 before a Polish court in Kraków—the same city where she’d once ruled as an overseer—Danz played the ultimate defense: obedience. “I only wrote what the commandant ordered,” she claimed, her voice steady as she shifted blame upward to the ghost of Heinrich Himmler and his chain of command. It was the Nuremberg defendants’ favorite alibi, but the judges saw through it. The prosecution laid bare her role in the systematic extermination of 15,000 women, linking her reports directly to gas chamber selections. On November 25, 1947, she was sentenced to life imprisonment, a verdict that echoed the gravity of her crimes.

Yet justice, in the fragile postwar world, proved fleeting. After nine years in a Polish prison, amid Cold War tensions and overcrowded cells, Danz was amnestied in 1956 and deported to West Germany. She vanished into obscurity, living quietly in Oldenburg as a seamstress, her past buried under layers of denial. For decades, she evaded further scrutiny, a footnote in Holocaust histories overshadowed by bigger names. But history has a way of exhuming the forgotten. In 1996, a dusty archive in Berlin yielded a bombshell: a long-lost SS file detailing Danz’s direct involvement in the murder of teenage prisoners at Mauthausen in September 1942. The document described how she had overseen the selection and gassing of adolescent boys and girls, deeming them “useless mouths” during a labor shortage. At 79, frail and wheelchair-bound, Danz was rearrested in a dramatic dawn raid. The trial in 1999 was a media circus, with survivors in their 70s and 80s taking the stand to relive nightmares. “She hasn’t changed,” one said, pointing at the stooped figure. “The eyes are still cold.” Convicted of accessory to murder, her age spared her a harsher sentence—three years in a minimum-security facility, where she served her time knitting and reading.

Freed by late 1999, Danz returned to her quiet life, but fate—or karma—had the final word. Just six months later, on May 15, 2000, she suffered a massive stroke and died at 82, alone in her apartment. No eulogies, no remorseful confessions; just a silent end to a life built on whispers of death.

Luise Danz’s story is a haunting coda to the Holocaust’s symphony of suffering—a tale of how evil thrives not just in the spotlight of monsters like Mengele, but in the dim corridors of administration. Her quiet killings remind us that genocide isn’t always loud; it’s often a form of paperwork, a suggestion slipped into a file, a whip crack in the frozen night. As fans of history, we owe it to the 15,000 souls she condemned—and the millions more—to remember her not as a villain in a vacuum, but as a warning. In an age of bureaucratic overreach and moral apathy, Danz asks: How many “quiet killers” walk among us today? Share your thoughts below—what does her legacy teach us about complicity? Let’s keep the conversation alive, so the silenced voices of Auschwitz echo on.