THE SUICIDE THAT SILENCED A MONSTER: How Fritz Suhren, the commandant of Ravensbrück, escaped justice for his personal crimes _de107

This article contains detailed accounts of torture, sexual violence, medical experiments, and mass murder during the Holocaust. The content is deeply disturbing and may be traumatizing. We strongly advise caution when reading.

In the grim annals of Nazi atrocities, few figures embody the raw, personal sadism of the Holocaust as vividly as Fritz Suhren. As the iron-fisted commandant of Ravensbrück—the Reich’s largest concentration camp for women—he transformed the lakeside prison in northern Germany into a hellhole into which over 130,000 people, mostly women and children, were driven. Between 30,000 and 50,000 died there from starvation, overwork, mistreatment, in gas chambers, and through cruel medical experiments. Suhren, a mid-ranking SS bureaucrat who had risen through brutality, not only oversaw this death machine; he reveled in it, using whips and fists as instruments of terror. But in a final act of cowardice, his death – whether by his own hand or the swift justice of his tormentors – deprived the survivors and the world of a full reckoning and left his most heinous confessions unspoken.

Fritz Suhren, born on June 10, 1908, into a simple German farming family, was driven by ideological zeal. In 1928, at the age of 20, he joined the Nazi Party (NSDAP) and initially served in the Sturmabteilung (SA) before transferring to the SS in 1931. From 1934 onward, he was a full-time SS member, and his career was marked by ever-increasing cruelty. Stationed at the Sachsenhausen concentration camp in 1941, Suhren quickly proved his mettle as deputy commandant. There, he orchestrated one of the camp’s most infamous executions: He ordered the prisoner Harry Naujok, a German communist, to hang his fellow inmate Johann Brenner from a gallows rigged with a winch. The device slowly hoisted the victim upward, prolonging his agony by 15 excruciating minutes, while Suhren forced a young prisoner to stand silently beside the dying man. It was a prelude to the horrors he would unleash in Ravensbrück.

![THE ARREST OF FRITZ SÜHREN [Allocated Title] | Imperial War Museums](https://www.iwm.org.uk/sites/default/files/2020-04/c_whitehead_2.jpg)

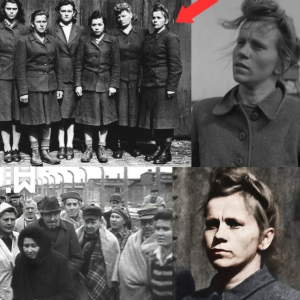

In August 1942, Suhren was appointed commandant of Ravensbrück, succeeding Max Koegel, another sadist who later committed suicide. He inherited a camp designed exclusively for women: political dissidents, resistance fighters, Jews, Roma, Jehovah’s Witnesses, and “asocials” such as lesbians and prostitutes, deemed unsuitable for the Aryan ideal. Nestled in the Mecklenburg forests near Fürstenberg, 90 kilometers north of Berlin, Ravensbrück’s idyllic setting masked the cruelty that reigned there. Under Suhren’s rule, the camp grew from 7,000 to over 40,000 prisoners, with satellite camps providing forced labor for armaments factories. His mantra was simple: annihilation through exhaustion. The prisoners received rations that were barely enough to survive – rotting bread, watery soup with sawdust – while they were forced to work 12-hour shifts, breaking stones, sewing uniforms or digging trenches in sub-zero temperatures, dressed only in worn-out rags.

But Suhren’s rule was not a detached administration, but rather a stage for personal vendettas. Eyewitness accounts from survivors, documented in postwar trials and memoirs such as Odette Sansom’s ” Parachute in Danger ,” paint a picture of a brutal tormentor. Tall, broad-shouldered, and with a permanent mocking grin, he patrolled the barbed wire fences with a riding crop attached to his belt, arbitrarily selecting women for “disciplinary measures.” He was notorious for whipping prisoners to death in the camp yard. His blows struck their bare backs with rhythmic precision until flesh tore and bones broke. “He beat them until they no longer moved,” recalled the Polish survivor Maria Kusmierczuk in her testimony at the Ravensbrück trials in Hamburg in 1947. Suhren reveled in the spectacle, often lighting a cigarette amidst the screams to ensure the assembled prisoners witnessed the “lesson.” Personal punishments were his specialty: for minor offenses like whispering or stepping out of formation, he would drag women to his office for individual interrogations. There, isolated from the gaze of the block, he would unleash his unbridled rage—pounding faces until jaws shattered, kicking ribs until lungs collapsed, or, worse, subjecting them to sexual humiliations that left indelible scars on their psyches.

These acts were not mere outbursts; they were Suhren’s trademark. Unlike the clinically detached doctors of Auschwitz, Suhren’s violence was tactile, eroticized in its intimacy. He headed the “Pleasure Department”—a euphemism for a brothel where “privileged” prisoners were forced to have sex with male guards and favored fellow inmates; many died of venereal diseases or by suicide. He personally selected the women for this humiliation, his gaze lingering as they were presented to him. And when Heinrich Himmler’s chief physician, Karl Gebhardt, arrived in 1942 demanding test subjects for “medical research,” Suhren initially refused—most of the women in Ravensbrück were “politicians,” not Jews, he protested. But an order was an order. Suhren apologized profusely in a letter to Gebhardt and ultimately provided hundreds of test subjects for experiments involving sterilization with radium injections, infection of limbs with gangrene bacteria, shattering of bones to transplant fragments without anesthesia, and testing of sulfonamide drugs on deliberately damaged tissue. Suhren even visited the “infirmary” and chuckled at the writhing individuals strapped to tables.

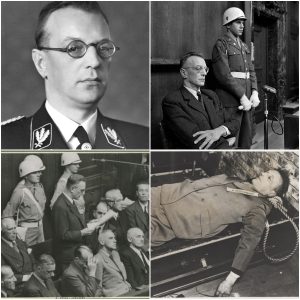

As the Red Army retreated in April 1945, Suhren’s facade began to crumble. Facing imminent liberation, he orchestrated death marches that claimed thousands more lives, leaving the weak to freeze to death in ditches. In a bizarre attempt to gain mercy, he dragged British SOE agent Odette Sansom—whom he delusionally believed to be Winston Churchill’s niece—into his Mercedes at gunpoint and drove toward the American lines. “Take this,” he reportedly said, handing her his Walther PPK as a sign of surrender, hoping her “connections” would protect him. Sansom, who had endured torture without breaking, pocketed the weapon as a trophy; it is now on display at the Imperial War Museum in London. Arrested by British troops, Suhren seemed to await his fate.

But the monster escaped again. In 1946, while awaiting extradition to the Hamburg Trials—in which 16 other Ravensbrück staff members were convicted—Suhren escaped from British custody along with labor director Hans Pflaum and went into hiding on the Bavarian black market. For three years he evaded prosecution; his disappearance left a gaping wound in history. Although the Hamburg Trials documented the systematic atrocities at Ravensbrück, they could only speculate about Suhren’s direct role and piece together the testimonies of survivors without questioning him. “His escape obscured the full extent of his personal crimes,” noted State Prosecutor Telford Taylor in his postwar reflections. Recaptured by US troops in 1949, Suhren was extradited to a French military court in Rastatt, where a jury of Allied survivors—French, Dutch, and Luxembourgish—tried his case from February to May 1950.

The trial was a true nightmare. Dozens of witnesses testified about Suhren’s whippings, the rapes in his office, and the experiments he authorized. The interrogation transcripts document Suhren’s defiance: While he admitted to having “maintained order,” he denied details and shifted the blame to superiors like Himmler. “I was following orders,” he said with a shrug, repeating the defense strategy of the Nuremberg Trials. On May 15, 1950, the verdict was delivered: guilty of war crimes and crimes against humanity. Death by firing squad. Suhren’s end came swiftly on June 12, 1950—just two days after his 42nd birthday—in a field surrounded by pine trees near Rastatt. Eyewitnesses described how he stared down the barrel of the gun without remorse; his last words were a muttered curse.

In death, Suhren achieved a perverse victory. His escape and his abbreviated testimony robbed the world of deeper insight into the psyche of a man who murdered not merely out of ideology, but for the pleasure of the bloody corpses at his feet. Survivors like Sansom, who lived until 1995, bore the burden of unspoken horrors; their justice was only partial. Ravensbrück’s ghosts whisper of what might have been revealed had Suhren survived and endured every single lash of his whip. His story is not one of redemption or even poetic irony—it is a warning that while monsters like him may die, the silence they spread remains, a final crack of the whip in the darkness.

Today, the Ravensbrück Memorial stands as a monument: a museum amidst the ruins, where wildflowers bloom over mass graves. It honors the mothers who resisted, survived, and bore witness. Suhren’s crimes, though partly shrouded in mystery, reinforce the promise: Never again. Yet, in the face of resurgent hatred, his unpunished atrocities serve as a warning to remain vigilant. The monster may have been silenced, but the memory demands that we speak out.